The Story of Rome (10 page)

But the Æquians were a restless people. They soon broke the treaty, and, led by their chief Clœlius, pitched their camp on one of the spurs of the Alban hills, and began to burn and plunder as of old.

The Romans, furious at this breach of faith, sent an embassy to demand redress.

But Clœlius mocked at the Roman ambassadors, and laughingly bade them lay their complaints before the oak-tree, under which his tent was pitched.

The angry ambassadors took the oak and all the gods to witness that it was not they but the Æquians who had broken the treaty and begun the war. Then hastening back to Rome, they told how insolently they had been treated.

An army, with the Consul Minucius at its head, was at once dispatched to punish the Æquians.

Clœlius was a skilful general, and as the Roman army advanced he slowly retreated into a narrow valley. The Romans foolishly followed the retreating Æquians, as Clœlius intended that they should.

When the enemy was in the midst of the valley, hemmed in by steep hills on either side, Clœlius ordered a band of soldiers to guard the end by which the Romans had entered. Minucius was caught in a trap.

But before the Æquian general had secured the end of the valley, five Roman soldiers had escaped, and these, putting spurs to their horses, rode swiftly to Rome to tell how the Consul and his army were ensnared.

As the terrible news spread, Rome was stricken with panic. She feared the enemy would soon be at her very gates, and their second Consul was far away, fighting against the Sabines.

In their dismay, the Senate determined to appoint a Dictator, who would have supreme authority as long as the country was in danger.

Neither the Senate nor the people had any doubt as to whom they should turn to in their trouble. There was one man only who could save the country. He was a noble patrician who had already held positions of trust in the State, and he was, too, a proved and experienced general.

Cincinnatus, or the Crisp-Haired, was the name of the man to whom the Senate now determined to send. This strange name had been given to him because his hair clustered in curls around his head. The family of the Cæsars also received their name from their curls.

When the messengers from Rome reached the home of the patrician it was still early morning, but Cincinnatus was already at work in his fields. For he, as many a noble Roman in the olden days, cultivated his own estate. As the heat was great, Cincinnatus had thrown aside his toga, and was digging with bare arms.

One of this household ran to the fields to tell that messengers had arrived from Rome and wished to speak with him.

So, putting on his toga that he might receive the messengers of the State in suitable guise, the simple-minded patrician hastened to the house.

No sooner did he hear that his country was in danger, and that he had been chosen Dictator, than he speedily went to Rome, where the people greeted him with shouts of joy.

Cincinnatus lost no time in assembling a new army. Going to the Forum, he ordered that the shops should be closed, and all business cease until Rome was safe.

All who could bear arms were told to assemble without delay on the Field of Mars, bringing with them twelve stakes for ramparts and food for five days.

That same evening, before the sun sank to rest, the new army had left Rome, and by midnight it was close to the valley in which Minucius, with his legions, lay entrapped.

Here the Dictator commanded his men to halt and throw their baggage in a heap. Then he ordered trenches to be dug round the enemy's camp, as noiselessly as might be, and the stakes they had brought with them to be driven into the ground.

When this was done, Cincinnatus bade his soldiers shout with all their strength. The noise aroused the Æquians, who sprang to their feet, and in terror seized their arms.

But the legions of Minucius also heard the shouts, and recognizing their own war-cry, they also grasped their weapons and attacked the Æquians.

They, seeing that they were surrounded by the enemy, with no way of escape possible, surrendered to the Dictator, begging him to be merciful.

Cincinnatus spared the lives of Clœlius and his soldiers, but he made the men pass under the yoke, after which they were allowed to find their way back to their mountain retreats.

The yoke was formed of three spears, and as the soldiers stooped to pass beneath this rough erection they had to lay aside their cloaks and surrender their arms.

Clœlius and the other leaders of the Æquians were kept prisoners.

Then the Dictator having freed his country from danger, returned in triumph to Rome. At the end of sixteen days he resigned the Dictatorship, and went back to his home, honoured by the people and crowned with glory.

Soon he was again to be seen digging or ploughing in his fields, contented as of yore.

CHAPTER XXIX

The Hated Decemvirs

T

HE

tribunes, you remember, were appointed to protect the people from the cruelty of the patricians.

As they were chosen from among the plebeians themselves, they did not understand the laws of their country as well as did the nobles, who had ever guarded them as they might have guarded a mystery.

So when the tribunes tried to gain justice for those who appealed to them, they often found their plans thwarted by the patricians, because of their superior knowledge of the law.

Thus, in spite of all that the tribunes could do, the people still suffered under the oppressions of the nobles.

So restless and discontented did the plebeians become, that in 451

B

.

C

.

three patricians were sent by the Senate to Greece to find out how the people were governed in Athens.

The nobles of Greece were wiser and more cultured than those of Rome, and may have been supposed to have discovered how best to rule those under them.

Whether the three ambassadors drank deep of the wisdom of the Greeks or no, they returned to Rome with a new plan for the government of the country.

It would be well, said the ambassadors, if, for a time, there should be neither Consuls nor tribunes. In their place ten men or decemvirs (decemvirs being the Latin for ten men) should be chosen from among patricians and plebeians alike, to rule the country and reform her laws.

Until now the laws had been unknown to the people. But the ambassadors said that the reformed laws should be written on tables of brass and be hung up in the place of assembly, so that the people might read and understand them.

The new laws were called the Laws of the Twelve Tables, and for many long years they were obeyed. In the time of Cicero, schoolboys had to learn these laws as part of their regular lessons, while they were, as we would say, in the lower forms.

Like the Consuls, the decemvirs were elected only for one year, each of them during the year having in turn full authority.

At first the decemvirs tried to please the people. They worked hard to reform the laws, and before their year of office came to an end, ten of the twelve tables had been revised.

It was determined that the decemvirs should be re-elected for the following year that they might finish the code of laws which they had begun.

But Appius Claudius, who had been the chief among the first year's decemvirs, was not satisfied that this should be so, and he saw to it that more plebeians should be elected among the second year's decemvirs.

He hoped by doing this to persuade the people that he was their friend, but before long it appeared that he was a true friend to neither patrician nor plebeian.

The new decemvirs, with Appius Claudius at their head, soon struck dismay into the hearts of the people by going to the Forum, with a band of one hundred and twenty lictors. The lictors carried with them not only rods, but, as in earlier days, axes were concealed among the rods, which was a sign that the decemvirs had power over life and death.

Nor did the decemvirs scruple to use their power, banishing or putting to death those who displeased or opposed them, and seizing their property for themselves. When their year of office was nearly ended, the decemvirs had not finished the code of laws as they were expected to have done.

It was soon plain why they had seen no reason for haste, for, when the year came to an end, the decemvirs refused to resign.

Both patricians and plebeians were indignant, while the Senate, angry that the decemvirs did not consult it, had already, for the most part, left Rome.

To add to the confusion in the country, war now broke out with the Sabines and the Æquians.

One of the Roman armies was to be led by a plebeian tribune, who was loved by the people, for he had fought for his country in one hundred and twenty battles. On his way to join his army, this brave soldier was murdered, it was said by the order of Appius Claudius. The soldiers were furious at the loss of their leader, and the hatred against the chief of the decemvirs increased each day.

CHAPTER XXX

The Death of Verginia

A

PPIUS

C

LAUDIUS

did not go to the war. He stayed in Rome, and before long roused the temper of the people beyond control.

Verginius, a brave plebeian soldier, was with the army, and in his absence he had left his beautiful young daughter Verginia in the care of her nurse.

Verginius left his beautiful young daughter Verginia in the care of her nurse.

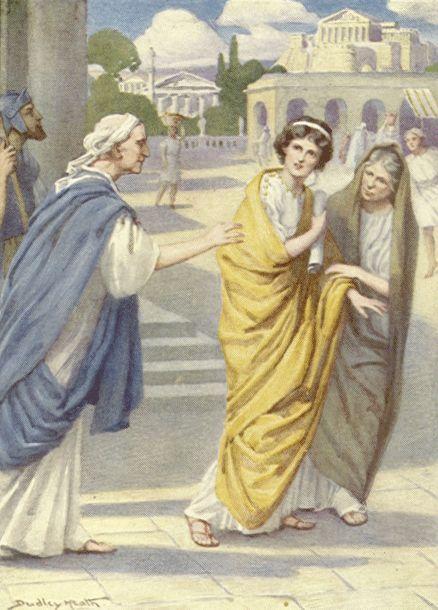

One day as the young girl was on her way to school in the Forum, Appius Claudius saw how beautiful she was, and he determined to take her away from her father and Icilius, to whom she was betrothed.

But although he did his utmost to persuade the maiden to go home with him, Verginia refused to leave her father's house.

Then Appius Claudius grew angry, and vowed to himself that he would take her away by foul means, since fair ones had failed.

So the tyrant ordered a man, named Marcus Claudius, to declare that Verginia was not a free Roman maiden, as Verginius had pretended, but was a slave belonging to himself.

This Marcus did, and then, seeing the girl one day in the Forum, he tried to lay hold of her. But her nurse cried aloud for help, so that a crowd quickly gathered, and hearing what had happened, it vowed to protect Verginia, until her father and her betrothed returned from the camp.

Then Marcius did as Appius Claudius had secretly bidden him. He said that he did not wish to harm the maiden, indeed, he was even willing to take the matter to law.

So, followed by the crowd, he led Verginia before the judge, who was no other than Appius Claudius.

Here Marcus announced that he could prove to Verginius that the maiden was not really his child, but belonged to a slave who lived in his house. Meanwhile he demanded that the maiden should be given into his charge.

But the crowd did not believe what Marcus said, nor did they care to let the young girl leave her home in her father's absence.

"Send to the camp for Verginius," cried the people, heedless of the angry looks of the judge. "Verginia is a free maiden, and shall stay with her friends until she is proved a slave."

With an effort, Appius Claudius concealed his real feelings, and, speaking with the dignity of a judge, he said: "The maiden belongs either to Verginius or to Marcus. As Verginius is absent, Marcus shall take charge of her until her father returns, when the case shall again come before me."

But to such an unfair sentence the people refused to submit. So fierce was their temper that they would have forced Claudius to leave the city had he not reluctantly allowed Verginia to stay with her friends until the following day. If Verginius did not then appear at his tribunal Marcus should claim the maiden without delay, said Claudius.

Icilius had by this time returned to the city, and he at once sent to the camp, beseeching Verginius to let nothing keep him from at once coming to Rome.

But Claudius also sent a messenger to the camp, bidding his officers on no account to allow Verginius to leave his post.

Fortunately, the messenger sent by Icilius reached the camp first, and Verginius was already hastening to the city when his officer received the order sent by Claudius.

The next morning Claudius went to the Forum, sure that before the day was over he would have secured Verginia.

What was his surprise and anger to see that Verginius, whom he had believed to be safely detained at camp, was already there by the side of his daughter, accompanied by many Roman matrons and a crowd of people.

The judge could hear the voice of Verginius as he drew near. He was speaking to the people, and Claudius knew too well how easily the passions of the mob could be roused.

"It is not only my daughter that is not safe," Verginius was saying; "who will dare henceforth to leave their children in Rome if I am robbed of my child?"

As the matrons listened they wept, thinking of the fate that might overtake their own dear daughters.