The Success and Failure of Picasso (6 page)

Read The Success and Failure of Picasso Online

Authors: John Berger

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Artists; Architects; Photographers

6

Easter procession in Lorca

Yet at the same time it must be remembered that Spaniards had not paid the price of progress as it was being paid in France or England. The wealthiest among them were land-owners, not bankers. As a class they served the Church, the estates, the army, and the absolute monarchy; they did not serve capital. This meant that their lives, although very provincially circumscribed, were not depersonalized and made anonymous by the power of money. (The cash nexus, which Carlyle was thundering against in England in the 1840s, does not exist in Spain even now.) It also meant that their class enemy was the peasantry, not a proletariat. A proletariat has to be outwitted and

tricked; peasants can mostly be ignored and occasionally intimidated by force. Consequently, the Spanish middle classes were not forced to be hypocritical: they were not trapped between their professed morality and what they needed to do to survive. Because there was no class they had to trick, they could at least be honest to themselves. Within strict limits, they could be proud and independent and could trust their own emotions. (This partly explains why Spaniards have the reputation in the rest of Europe of being so ‘passionate’.)

Spain then was separate. Its economy was predominantly feudal. The memories and hopes of its peasants were pre-feudal. Its large and unusual middle class, whilst maintaining many apparent connexions with contemporary Europe, had still not made the equivalent of a bourgeois revolution. The tragedy of Spain lay (and still lies) in this historical paradox. Spain is a country tied on an historical rack – the symbolic equivalent of its own Inquisition’s instrument of torture. It is stretched between the tenth and the twentieth centuries. Between them there have not arisen, as in other countries, those contradictions which can lead to further development: instead there is unchanging poverty and a terrible equilibrium.

The typical modern political movement in Spain was anarchism. As a youth in Barcelona, Picasso was on the fringes of this movement. The anarchism that took root in Spain was Bakunin’s variety. Bakunin was the most violent of the anarchist thinkers.

Let us put our trust in the eternal spirit which destroys and annihilates only because it is the unsearchable and eternally creative source of all life. The urge to destroy is also a creative urge.

It is worth comparing this famous text of Bakunin’s with one of Picasso’s most famous remarks about his own art. ‘A painting’, he said, ‘is a sum of destructions.’

The reason why anarchism is typical of Spain and why it achieved a mass following in Spain to a degree which it achieved nowhere else, is that, as a political doctrine, it also is stretched on an historical rack. It connects social relations as they once were under primitive collective ownership with a millennium in the future which is to begin suddenly and violently on the Day of Revolution.

It ignores all processes of development and concentrates into a single, almost mystical moment or act all the powers of an avenging angel born of centuries of endured and unchanging suffering.

Gerald Brenan, in his excellent book,

The Spanish Labyrinth,

records the following incident during the Civil War:

I was standing on a hill watching the smoke and flames of some two hundred houses in Malaga mount into the sky. An old anarchist of my acquaintance was standing beside me.

‘What do you think of that?’ he asked.

I said, ‘They are burning down Malaga.’

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘they are burning it down. And I tell you, not one stone will be left on another stone – no, not a plant not even a cabbage will grow there, so that there may be no more wickedness in the world.’

This is typically Spanish: the belief that everything – the whole human condition – can be violently and magnificently changed in one moment. And the belief has arisen because nothing has changed for so long, because in the end the Spaniard is forced to believe in a magical transformation in which the power of the will, the power of the wishes of men still uncomplicated by the moral nuances of a civilization in which each hopes to save himself first, can triumph over all material conditions, can triumph over the slow accumulation of new productive means which in reality is the only condition of progress. The terrible equilibrium of the rack produces from time to time a terrible impatience.

There is also an economic logic to the old anarchist’s outburst as he looks down at Malaga. (This logic does not necessarily enter his own considerations for he has long deserted logic – as any of us might if tied to the rack.) This is the logic of the fact that the Spanish ruling class have established nothing, have built nothing, have discovered nothing that can be of the slightest use to the peasants who are overthrowing them. Expropriate the expropriators! But here the original expropriators have added nothing to what they expropriated. There is only the bare land. This can once again be cultivated by a primitive collectivist commune. Everything else is

useless

– and therefore luxury and corruption are better burnt.

7

Spanish peasants returning from market

In such a situation it is inevitable that revolutionary energy becomes regressive: that is to say aims at reestablishing a more primitive but juster form of social relations, which frees men from human slavery but precludes them from the possibility of freeing themselves from the slavery of nature.

Picasso’s painting

Guernica

is said to be a protest against modern war, and is even sometimes claimed to be a kind of prophetic protest against nuclear war. Yet at the time when Guernica was razed to the ground by German Junkers and Heinkel bombers, most of the anarchists in Andalusia who had collectivized the land were unable to ‘expropriate’ a single piece of agricultural machinery. Such is the rack.

Yet, you may say,

Barcelona is not Andalusia; Barcelona is an industrial city and so surely the anarchism in which Picasso was involved was different? Superficially it was different. Picasso read Nietzsche and Strindberg.

4

The circle in which he moved was considerably influenced by

Santiago Rusiñol, a painter and critic, who had issued the following

fin-de-siècle

order of the day:

Live on the abnormal and unheard-of … sing the anguish of ultimate grief and discover the calvaries of the earth, arrive at the tragic by way of what is mysterious; divine the unknown.

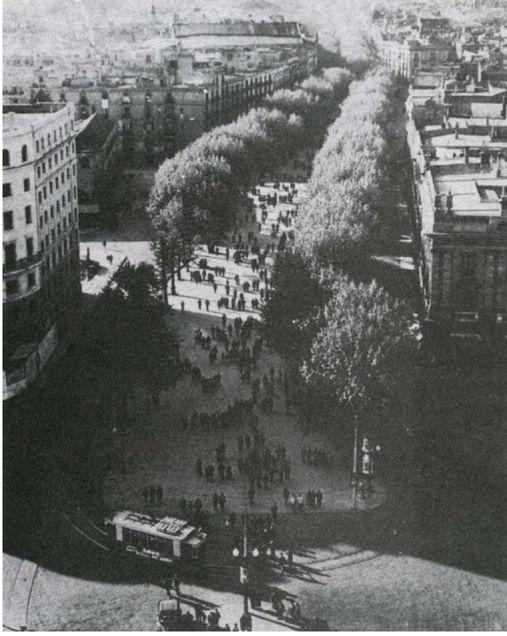

8

Barcelona. Las Ramblas

Nevertheless, Barcelona was not a city like Lyons or Manchester. The

fin-de-siècle

tone was adopted by some of its intellectuals because it was a provincial city trying to keep up with the capitals. But its own violence was real rather than imaginative, and its extremism was an everyday fact.

In 1906

Alezandro Lerroux, leader of the radicals in Barcelona, exhorted his shock-troop followers who called themselves the ‘Young Barbarians’ as follows:

Enter and sack the decadent civilization of this unhappy country; destroy its temples, finish off its gods, tear the veil from its novices and raise them up to be mothers to civilize the species. Break into the records of property and make bonfires of its papers that fire may purify the infamous social organization … do not be stopped by altars nor by tombs … fight, kill, die.

This is not very far from the old man looking down at Malaga. Neither of them can forgive. In Lerroux one can perhaps sense the beginning of fascism. But this word is often used too loosely. Incipient ‘fascism’ can exist whenever a class or a people feel sufficiently trapped. Fascism, in its modern and precise sense, applies to the exploitation of this feeling by imperialism and big business as a weapon against socialism. In Barcelona at the turn of the century this was not the case.

Barcelona was not fascist but simply lawless. Beginning in the 1890s bombs were being thrown. In 1907 and early 1908 two thousand exploded in the streets. A little after Lerroux’s speech twenty-two churches and thirty-five convents were burnt down. There were a hundred or more political assassinations every year.

What made Barcelona lawless was once more the historical rack. Three groups of interests were each fighting for survival. There was Madrid fighting for its absolutist right, as established by the Habsburgs in the seventeenth century, to live off the riches of its manufacturing province. There were the Barcelona factory-owners fighting for independence from Madrid and the establishment of a capitalist state. (Generally speaking their enterprises were small and at a low level of development. When they were on a larger scale – as in the case of the banks or railways – they were compromised by being tied to political parties and so run in the interests of bureaucratic graft rather than efficiency and profit.) Lastly there was an inexperienced but violent proletariat, largely made up of recent peasant emigrants from the poverty of the south.

Madrid, for its own interests, encouraged the differences between factory-owners and workers. The factory-owners, having no judiciary or state legal machinery with which to control their workers, had to dispense with legality and rule by direct force. The workers had to defend themselves against the representatives of Madrid (the army and the Church) and against the factory-owners. In such a situation, and with little political experience to help them, their aims were inevitably avenging and short-term – hence the continuing appeal of anarchism. Each group – one might almost say each century – fought it out with

pistoleros, agents provocateurs,

bombs, threats, tortures. All that in other modern cities was settled ‘legally’ – even if unjustly – by the machinery of the state, was settled privately in Barcelona in the dungeons of Montjuich Castle or by guerrilla warfare in the streets.

You may feel that what I have said about Spain has very little to do with Picasso’s own experience. Yet only in fiction can we share another person’s specific experiences. Outside fiction we have to generalize. I do not know and nobody can know all the incidents, all the images in his mind, all the thoughts that formed Picasso. But through some experience or another, or through a million experiences, he must have been profoundly influenced by the nature of the country and society he grew up in. I have tried to hint at a few of the fundamental truths about that society. From these alone we cannot deduce or prophesy the way that Picasso was to develop. After all, every Spaniard is different, and yet every Spaniard is Spanish. The most we can do is to use these truths to explain, in terms of Picasso’s subjective experience, some of the later phenomena of his life and work: phenomena which otherwise might strike us as mysterious or arbitrary.

Yet, before we do this, there is another aspect of Picasso’s early life which we must consider. The most obvious general fact about Picasso is that he is Spanish. The second most obvious fact is that he was

a child prodigy – and has remained prodigious ever since.

Picasso could draw before he could speak. At the age of ten he could draw from plaster casts as well as any provincial art teacher. Picasso’s father was a provincial art

teacher, and, before his son was fourteen, he gave him his own palette and brushes and swore that he would never paint again because his son had out-mastered him. When he was just fourteen the boy took the entrance examination to the senior department of the Barcelona Art School. Normally one month was allowed to complete the necessary drawings. Picasso finished them all in a day. When he was sixteen he was admitted with honours to the Royal Academy of Madrid and there were no more academic tests left for him to take. Whilst still a young adolescent he had already taken over the professional mantle of his father and exhausted the pedagogic possibilities of his country.

Child prodigies in the visual arts are much rarer than in music, and, in a certain sense, less true. The boy Mozart probably did play as finely as anybody else alive. Picasso at sixteen was

not

drawing as well as Degas. The difference is perhaps due to the fact that music is more self-contained than painting. The ear can develop independently: the eye can only develop as fast as one’s understanding of the objects seen. Nevertheless, by the standards of the visual arts, Picasso was a remarkable child prodigy, was recognized as such, and therefore at a very early age found himself at the centre of a mystery.