The Super Mental Training Book (19 page)

Read The Super Mental Training Book Online

Authors: Robert K. Stevenson

Tags: #mental training for athletes and sports; hypnosis; visualization; self-hypnosis; yoga; biofeedback; imagery; Olympics; golf; basketball; football; baseball; tennis; boxing; swimming; weightlifting; running; track and field

One player who does not mind that the public knows he has used hypnosis is Billy Casper, the two-time U.S. Open champion and five-time winner of the Vardon Trophy (low average score for the year). Correspondent Art Parra of the Orange County Register relates the circumstances which led Casper to give hypnosis a try:

In 1975, at age 44, Casper already had won 51 PGA tour events and more than $1.5 million in purses. Dark days began to set in and during 1980 Casper's winnings flopped to zero, a terrible shock to him and a surprise to his fans. [22]

Casper regarded his 1980 performance as unacceptable, commenting that "it was sheer agony go out there and play like a bum." He therefore took two major actions. One dealt with the mental side of his game, the other the technical. Stated Casper:

I was strengthened by a Salt Lake City hypnotist. He sliced the positive things from my career and spliced them together for a positive attitude.

Then I went to school. Sounds funny, doesn't it? But, we are never too old to learn and a two-month drill with Phil Rodgers re-polished my game. I knew I needed some instructional help, but was too proud to admit it.

Athletes who desire to achieve their potential must work on all aspects of their sport—mental, physical, and technical. This is what Billy Casper came to realize, and when he did this, things began to turn around for him. His game revived, and Casper decided to join the newly-formed PGA Senior Tour. In 1981, his first year on the Senior Tour, he won over $50,000, and in following years remained a leading money winner on the senior circuit. Casper cites three factors accounting for his success. They are: 1) his going to a hypnotist; 2) his attending the golf school, and 3) his playing the PGA Senior Tour, a tour which allows him to compete against players his own age.

Jane Blalock, winner of several tournaments on the LPGA Tour, considers the mental side of golf quite important. She told Women's Day writer Susan Edmiston that she engages in a meditation-like procedure before playing each round of a tournament:

I go into the locker room and find a corner by myself and just sit there. I try to achieve a peaceful state of nothingness that will carry over onto the golf course. If I get that feeling of quiet and obliviousness within myself, I feel I can't lose. [23]

The greatest player in the history of golf, Jack Nicklaus, uses a mental rehearsal technique while he competes. Nicklaus, who has won more major tournaments and money than any other golfer, employs imagery. Dan Lauck reports about how the imagery technique is woven into Nicklaus's game:

Jack Nicklaus stands there in the middle of the fairway and calculates. His caddy, Angelo, tells him the distance to the pin. Nicklaus judges the wind, Nicklaus asks for a club. He grips the club, stands behind the ball and looks toward the green, seemingly in a trance. What he is doing in this trance is imagining the shot. He imagines every shot; imagines setting up to the ball and swinging; imagines the trajectory of the ball; imagines the ball fading into the heart of the green, landing and backing up. He has been doing it for years and advocating that everyone else do it. [24]

Lauck is quite correct when he says Nicklaus advocates that every golfer should practice imagery; for example, Nicklaus's syndicated column of May 3, 1978 ("Play Better Golf with Jack

Nicklaus") contains this advice:

Confidence is the primary requirement in putting. If you think you'll make a putt, you probably will. If you don't think you'll make it, you almost certainly won't.

Form a positive picture in your mind of how the ball must behave to drop into the hole, then stick to your plan as you set up to and stroke the ball.

The imagery technique Nicklaus practices is easy enough for any golfer to do. Whatever your sport, you can employ the technique, modifying the mental picture to suit your needs. Imagery is not only easy to use, but highly effective. Ben Hogan, one of golfs greatest legends, had no trouble using imagery, and certainly was an effective shot-maker. Hogan, the four-time U.S. Open Champion, used imagery in much the same way that Nicklaus does. Dr. Maltz, in his book Psycho-Cybernetics, describes how Hogan employed the technique:

When Ben Hogan is playing in a tournament, he mentally rehearses each shot, just before making it. He makes the shot perfectly in his imagination—"feels" the clubhead strike the ball just as it should, "feels" himself performing the perfect follow-through— and then steps up to the ball, and depends upon what he calls "muscle memory" to carry out the shot just as he has imagined it.

Hogan won the U.S. Open in 1948. The next year be was involved in a nearly fatal automobile accident. Doctors doubted that he would ever be able to walk again. Hogan not only recovered to where he could walk again, but also resumed playing tournaments. In 1950 he won his second U.S. Open, culminating one of sports' greatest comebacks. He followed this achievement with victories in the Open in '51 and '53.

Hogan used imagery on the golf course and off the course as well. Dr. Maltz says that "he kept a golf club in his bedroom, and daily practiced in private, swinging the club correctly and without pressure at an imaginary golf ball." Hogan's thorough job of mental rehearsal—using imagery before and during competition—sets a standard for athletes to emulate. If you feel that the use of mental disciplines will not help you because you are lacking in physical talent, keep in mind that Ben Hogan weighed only 135 pounds, and he made it to the top.

Why is imagery effective? Dan Lauck, looking into the matter, determined that psychologists can only surmise why it works. He reports that Dr. Thomas Tutko, author of Sports Psyching (1976), "believes that during imagery the mind acts as a computer, programming muscle actions for later on." Whatever the reasons, it seems you cannot lose by giving imagery a try. Nicklaus does not even close his eyes while employing the technique; so, practicing imagery places no special demands on you.

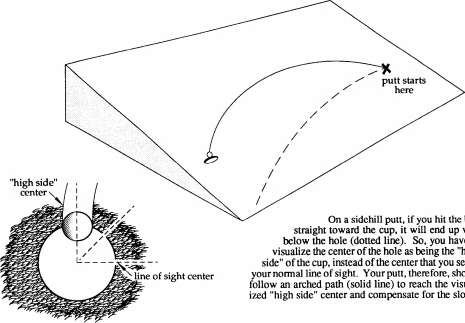

If you still have questions about how to go about using imagery for your golf game, read Tom Watson's outstanding book, Getting Up and Down (1983). Watson, perhaps the best golfer of the 1970s, advocates that you use visualization (imagery) while you play, and presents several illustrations in his book showing how your mind should be picturing a putt, approach shot, etc. For example, in Getting Up and Down he says this about a sidehill putt:

On all sidehill putts, consider that the center of the hole effectively shifts, and you have to visualize the center differently. You hear television commentators say a pro hit a breaking putt right in the center of the cup, but that's not correct. The "high side" of the cup becomes the center, and that's where you want the ball to enter. I've even had the ball drop in—literally—the back of the hole.

THE SUPER MENTAL TRAINING BOOK

"high side 1 center

\ line of sight center

On a sidehill putt, if you hit the ball straight toward the cup, it will end up way below the hole (dotted line). So, you have to visualize the center of the hole as being the "high side" of the cup, instead of the center that you see in your normal line of sight. Your putt, therefore, should follow an arched path (solid line) to reach the visualized "high side" center and compensate for the slope.

With this advice to visualize the center of the cup differently comes a drawing, similar to the one appearing on this page. Another illustration in Getting Up and Down shows Watson mentally picturing himself hitting a perfect shot out of a bunker. Beneath this illustration appears the following recommendation, with the heading, "See the shot before you play it":

The most important aspect of any shot is to visualize what you want to do before you address the ball and swing. Visualization is creating a game plan. Visualize the ball flying through the air, bouncing, then rolling up to the hole.

Watson goes on to relate how visualization helped him save par on the ninth hole of the 1981 U.S. Open (he had hit into a deep bunker), recalling that "I visualized a six-inch landing area just over the lip, and then popped the ball up and hit that spot. The ball landed about three feet short of the hole."

One good visualization putting drill Watson illustrates is where you "just hit to an imaginary circle around the hole and try to leave yourself with second putts no longer than three feet." In the illustration a putter lies flat on the green, its head in the hole, and rotated 360 degrees, demarcating the circular area Watson wants your putts to stop in (the metal shaft portion of the club forms the circle's radius).

Throughout Getting Up and Down Watson offers several "mental tips" which often involve visualization. Each tip appears on a separate page for emphasis. If you are a golfer, these tips are definitely well worth reading. Watson's book, being one of the few sports books actually illustrating what the mind should be picturing during competition, qualifies as instructive reading for

most athletes; this is because, irrespective of one's sport, the illustrations make it easier to understand the principles of visualization. As the old saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Speaking of visualization, it was finally revealed that the Los Angeles Lakers utilized the technique during Pat Riley's tenure as head coach (1981-1990); this as reported by Orange County Register writers Laura Saari and Jane Glenn Haas. Saari and Haas relate in a July 1, 1990 article that Irvine Company owner Donald "Bren and Riley often discuss visualizing techniques—the psychology of imagery that Riley used with his basketball team."[25] Other important details, such as how often Riley had his players practice visualization, the Register reporters do not provide. We can say, though, that excellent results generally materialize whenever gifted and well-conditioned athletes participate in a properly-presented mental training program. And, in the case of the Lakers, under Riley's guidance, Los Angeles won the NBA Championships in 1982, 1985, 1987, and 1988, earning themselves the Team of the Decade (1980s) accolade.

In this chapter we have discovered how certain professional athletes—several of them superstars—improved their athletic performance by using imagery, self-hypnosis, meditation, or yoga. By so doing, these athletes also enhanced their earnings; in the case of Jack Nicklaus, for instance, we are talking about many millions of dollars in winnings and endorsements. Some pros do not want it known that they use mental training strategies. Perhaps this is because they do not wish to let their competition in on a good thing—and we cannot blame them for that! But, other professional athletes have stepped forward, publicly sharing their positive experiences with mental disciplines. We should listen to these athletes, for they have nothing to hide and a message to tell. And this message is: the regular employment of mental training strategies will definitely help you achieve and maximize your athletic potential. So, give them a try. You'll be glad you did.

FOOTNOTES

1. Bill Shirley, "The Eastern Bloc Comes Into L.A. With a Head Start," Los Angeles Times, January 25, 1984, Part III,

P . i.

2. "Sports and Hypnosis," Bulletin of the Association to Advance Ethical Hypnosis, Vol. 84, 1979.

3. Ibid.

4. William S. Kroger, Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1977), p. 123.

5. Scott Ostler, "Chones Comes to Play as Lakers Top Pistons," Los Angeles Times, February 7, 1981, Part III, p. 1.

6. Scott Ostler, "The Philosopher Who Goes to the Boards," Los Angeles Times, November 13, 1979, Part III, p. 1.

7. "Kareem Realizes Importance of Being Kareem," Los Angeles Times, June 27, 1987, Part III, p. 18.

8. Rebecca Bricker, "Psychologist Barbara Kolonay Helps Athletes Train Themselves to Overcome the Clutch," People Weekly, February 1, 1982, pp. 33-37.

9. Kolonay gathered together a group of basketball players to improve their free throw percentage. She split the players into eight teams. Two teams she taught to use imagery, combined with a relaxation procedure. The players on these two teams, after going through a relaxation segment, were to imagine the entire free throw shooting sequence—from first approaching the line, to shooting the ball and watching it go through the basket. Needless to say, the two teams doing this improved more on their free throw shooting than the other teams. The improvement was approximately 6%. This may not seem much, but as any coach is keenly aware, the slightest improvement in performance can mean victory.

10. Michele Himmelberg, "Mind Games," Orange County Register, August 20, 1985, p. CI.

11. Ibid.

12. For the record, Portland finished the season in second place in the Pacific Division, but lost in the first round of the playoffs to Denver, 3 games to 1. After the playoffs Coach Ramsay, the second winningest coach in NBA history behind Red Auerbach, was fired, ostensibly because he did not get along with some of his players.

13. During his first two seasons with the Clippers, Benjamin performed, to phrase it charitably, considerably below

expectations, making Miller's optimistic assessment of the center seem way off the mark. An indication of how inaccurate Miller's assessment proved can be seen in the negative comments about the player that emanated from all directions, a sampling of which follows. Sam McManis, L.A. Times sportswriter, noted that "Benjamin's only consistency so far is that he's usually late for practice and is the Clipper most likely to miss a team flight" (see "Opportunity Knocks, but Benjamin Isn't Home", Los Angeles Times, November 29, 1985). Clippers Coach Don Chaney remarked after one game, "When I put him (Benjamin) in a game, I at least expect a few rebounds and (him to) run up and down the court. He's not going to play if he can't do that" (see "Clippers Lose to Warriors in Horror Show," Orange County Register, December 6, 1985). Meanwhile, Doug Moe, coach of the Denver Nuggets, characterized Benjamin as "a (expletive) dog" (see "Clippers Should Look to 1986-87," Orange County Register, March 11, 1986).