The Super Mental Training Book (53 page)

Read The Super Mental Training Book Online

Authors: Robert K. Stevenson

Tags: #mental training for athletes and sports; hypnosis; visualization; self-hypnosis; yoga; biofeedback; imagery; Olympics; golf; basketball; football; baseball; tennis; boxing; swimming; weightlifting; running; track and field

Recent Developments

217

100%

P E R F O R M A N C E

75%

50%

25%

AROUSAL LEVEL

(Emotional Excitement; Anxiety)

Athlete #1 -

Athlete #2=

100

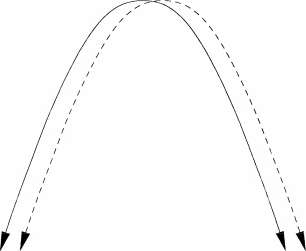

The inverted "U" varies from athlete to athlete. An optimal arousal level for one athlete will not necessarily be an optimal level for another. Each athlete, therefore, needs to be individually tested to determine what his optimal level of arousal is. Such indicators as heart rate, body temperature, and skin conductance, when compared to performance, help define one's optimal and less-than-optimal arousal level.

In our Tennis chapter Bob Payan related how he gave himself autosuggestions while driving a truck one summer: "I tried to do this as much as I could while driving the truck, because driving is boring. I did this especially if I had a tournament coming up. . ." Payan went on to win three straight tennis tournaments, but that is not the point here. The point is, as Dr. Ravizza and Dr. Nideffer contend, you can use the stretchout period during practice to incorporate mental training; you can blend it into drill work as well. You can also perform various forms of mental rehearsal while driving (Jack Youngblood, we recall, practiced visualization while in traffic), or better yet for the athlete, while sitting in the team bus on the way to the competition. Bill Russell, remember, developed his "mental camera" visualization technique while riding on the team bus (see Professional Athletes chapter). So, coaches cannot with much justification cite lack of time as a reason to forgo incorporating mental training into their sports program.

As I mentioned earlier, the Cal State Fullerton varsity teams Dr. Ravizza works with (gymnastics, Softball, and baseball) have done very well, with baseball, for example, winning the college World Series in 1984. Dr. Ravizza, smartly, takes virtually no credit for the teams' accomplishments, explaining:

I do not know what impact my work has on championships; I want to be real clear on that. I think the coaches are doing most of the work. I'm doing 1%. Now, that 1% in a high pressure situation can be crucial. All I guarantee to a coach is that: 1) the athlete is going to be more aware and more conscious of what he is doing on the field—that I will guarantee; 2) the athlete will enjoy his performance more. If those two things are going on, it is very likely that the performance will improve.

Though Dr. Ravizza downplays his contributions, positive reviews spread about his work. After the '84 College World Series, Marcel Lachemann, the pitching coach for the California Angels, contacted Dr. Ravizza about setting up a mental training program for the Angels pitchers. The Cal State Fullerton professor agreed to make a presentation to the pitchers, and see what interest the players would have in participating in a voluntary mental training program. Dr. Ravizza describes the developments:

Basically, I was brought in to work with the pitching staff. I went to Spring training (in 1985), spent a week there with the Angels pitchers, and presented the whole mental training program to them. I talked with them about concentration, relaxation, dealing with the pressure—most of it being performance-related. Out of 25 pitchers, 20 expressed interest in the program, said they wanted to go to more sessions, which they did while I was there.

Then during the season I was available. I would go down to the stadium on a home stand for two or three games, and I would be available to see the players one-on-one. And with the Angels—and what I see in professional athletics—it's all one-on-one. It's not going to be group session.

The Angel management brought me in to introduce the program, and then after that it was a matter of the players picking up. The players compensated me on an individual basis.

The initial presentation Dr. Ravizza made to the Angels pitchers occurred March 16, 1985, and was videotaped. This videotape, which I viewed, contains a lot of good tips about applying mental training to the pitching position. For instance, Dr. Ravizza says that a pitcher needs to concern himself with the time frame from when he catches the ball from the catcher to when he places his foot back on the rubber. Use this time to "regroup." Develop a "pre-pitch routine," he says. Whenever negative thoughts need to be dissipated (because the shortstop just made an error, etc.), this routine might call for the pitcher "picking up some dirt, going to the resin bag—let it go;" or, "maybe tighten your glove—let it release." At the same time the pitcher should face the outfield.

Only after the negative emotions have been released should the pitcher turn around. Because, as Dr. Ravizza incisively points out, "any time you're facing home plate, your energy is positive— you're up. Home plate does not deserve negative energy."

To establish the "pre-pitch routine," Dr. Ravizza informed the Angels pitchers that certain skills needed to be learned, such as relaxation and imagery. Again, the pitchers were notified that participation in the mental training program was voluntary, and that the program was designed to develop consistency in performance over a 162-game schedule. In terms of an arousal versus performance chart, Dr. Ravizza told the players they should strive to get their performance to regularly fall in the top quarter of the inverted "U"; this is a realistic goal, he went on, because during a long season very rarely can any pitcher perform at his absolute peak for more than one or two games.

There is little reason why athletes and coaches cannot become their own sports psychologists. The benefits of achieving self-sufficiency in one's own mental training are as numerous as they are substantial; plus, the ease with which one can develop this capability is well-documented, not only in this book, but in hundreds of other books and articles. However, despite all the resources available to help one become proficient in the use of mental rehearsal techniques, some athletes and coaches still feel the need to call in an outside expert. If you ever decide to enlist the services of a sports psychologist, keep in mind the conditions Bryant J. Cratty suggests should be in place and adhered to whenever such an undertaking is initiated. These conditions, spelled out in Cratty's book, Social Psychology in Athletics (1981), act to protect the athlete, and increase the odds that the mental training program will succeed:

1. The association between the team, coach, and social psychologist [Cratty's name for "sports psychologist"] should be a prolonged and professional one. It should last at least an entire sports season, and preferably longer.

2. The social psychologist should avoid excess exposure to the press. His job is to help the team's performance and the emotional health of all concerned, not to enhance his own reputation by seeking publicity.

3. The calling in of a behavioral scientist should be looked on as a form of preventive medicine, and should not always be a reaction to the onset of problems. Rather, the behavioral scientist's role should be looked on as a positive one, meant to enhance performance, rather than only prevent a future problem or reduce a present one.

4. The athletes often-limited time and energy should be considered at all times, by both the coach and psychologist, when setting up an evaluation and counseling program. Personal counseling should be optional, not mandatory. [50]

Fulfilling the requirements of Condition #1 is not only desirable, but quite attainable. For example, Dr. Ravizza worked with the Angels pitching staff again during the '86 season, and for the '87 and '88 seasons helped batters as well as pitchers. "About half of the team, he reports, utilized his mental training expertise. (Since 1989 Dr. Ravizza's assignment with the Angels organization has been to assist their minor leaguers.) As for the remaining conditions, we can see that they were easily adhered to by Dr. Ravizza in his work with the Olympic field hockey team, let alone with other clients. So, putting two and two together, we see that Cratty's guidelines are far from impossible to meet; instead, they are definitely within reason.

Having now presented you many sound mental training approaches in this chapter, all that remains to be seen is what reasonable course of action you will take to improve your mental preparation capabilities.

FOOTNOTES

1. Bud Winter, Relax & Win: Championship Performance in Whatever You Do, (San Diego, California: A. S. Barnes, 1981).

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. One feature of Winter's "relaxation routine" was its elimination of wrinkles on the forehead—further evidence that the technique can rightfully be called hypnosis. As Leslie LeCron, author of Self Hypnotism (1964), states in his book, "One of the signs of hypnosis is a smoothing out of the facial muscles, with a lack of expression shown. . ."

7. Winter, op. cit.

8. Frank Schubert, Psychology from Start to Finish, (Toronto: Sport Books Publisher, 1986), p. 97.

9. Ibid., pp. 97-98.

10. Ibid., pp. 99-100.

11. Y. G. Kodzhaspirov, "Monotony in Sport and Its Prevention Through Music," Soviet Sports Review, September, 1985, Vol. 20, No. 3, p. 105.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid., p. 106.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid., p. 108.

16. These three tapes are available from: VEJE, Box 16017, S-70016, Orebro, Sweden.

17. Lars-Eric Unestahl, "New Paths of Sport Learning and Excellence," (published by: Department of Sport Psychology, Orebro University, Box 16017, Orebro, Sweden), p. 3.

18. Ibid., p. 11.

19. Ibid., p. 7.

20. Ibid., p. 8.

21. Ibid., p. 10.

22. Ibid.

23. Recall that this is exactly what gymnastics champion Boris Shaklin did ("I would think of an exercise that I had done particularly well in the past, and my muscles would feel the rhythm. That's all." )

24. Unestahl, op. cit., p. 13.

25. Ibid., pp. 13-14.

26. Eugene F. Gauron, Mental Training for Peak Performance, (Lansing, New York: SportScience Associates, 1984), p. vii.

27. Robert M. Nideffer, Athletes' Guide to Mental Training, (Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc., 1985), p. 43.

28. Prior to the 1984 Olympics Dr. Nideffer, as President of Enhanced Performance Associates, worked with Canadian divers and Australian sprinters, for which he was remunerated. He also voluntarily helped '84 U.S. Olympic track and field athletes with their mental preparation, receiving only expenses. Beth Ann Krier, L. A. Times reporter, asked Dr. Nideffer if he would work for the Soviet Olympic team. Responded the sports psychologist: "Of course I would. I'm interested in the performer, not his or her country. I'd work for Stalin if I thought I could make him a better person" (see "Olympians Exercising in Mind Arena," Los Angeles Times, June 7, 1983). Whether Dr. Nideffer would work with Stalin for a fee, I'll leave up to the reader to decide.

29. Nideffer, op. cit., pp. v-vi.

30. As a corollary to this, Dr. Nideffer offers relaxation tapes for athletes experiencing difficulty in sleeping the night before a major competition. These tapes are available from: Enhanced Performance, 12468 Bodega Way, San Diego, CA 92128.

31. This publication is available from: Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc., Box 5076, Champaign, Illinois 61820.

32. For subscription information, contact: Soviet Sports Review, P. O. Box 2878, Escondido, CA 92025.

33. John M. Silva and Robert S. Weinberg, ed., Psychological Foundations of Sport, (Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc., 1984), p. 146.

34. Ibid., p. 149.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid., p. 155.

37. Ibid.

38. Ibid., p. 153.

39. Ibid., p. 154.

40. Ibid., pp. 154-155.

41. For membership information contact: AAASP, c/o Jean Williams, Exercise and Sport Science Dept., University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721.

42. Silva and Weinberg, op. cit., p. 39.

43. Ibid., p. 43.

44. Steven R. Heyman, "The Development of Models for Sport Psychology: Examining the USOC Guidelines," Journal of Sport Psychology, Vol. 6, No. 2, 1984, p. 131.

45. Kenneth S. Clarke, "The USOC Sports Psychology Registry: A Clarification," Journal of Sport Psychology, Vol. 6, No. 4, 1984, p. 366.

46. Ibid.

47. For information on this tape and other mental training aids Dr. Ravizza markets, contact: Kinesis, 530 Idaho, Santa Monica, CA 90403.

48. The Cal State Fullerton professor has apparently succeeded in this endeavor. According to Dick Wolfe, head coach of the men's gymnastics team at CSF, "our athletes are becoming aware of themselves and that they're responsible for their actions" (see "He Helps People Ease Pressure," Los Angeles Times, March 2, 1984). Dr. Ravizza, continues Coach Wolfe, "has made a difference to the gymnasts since I let him come on my turf four years ago. It has taken quite a while but some of the guys are finally admitting they're full of stress and at times were afraid. I guess it was a macho thing not to tell us."

This remark roused my interest, and I thought it would be instructive to get a more in-depth understanding of the coach's perspective on mental training and Dr. Ravizza's work. So, I interviewed Coach Wolfe, the 4-time national gymnastics Coach of the Year, on April 23, 1986. Coach Wolfe's comments appear in Appendix 1, and reveal that a sports psychologist can be much more than a mental trainer.