The Swarm (79 page)

Crowe rested her elbows on the table. âI appreciate the warm welcome.' She glanced at Vanderbilt. âSome of you may know that SETI's efforts haven't met with particular success. Given the sheer size of the known universe - at present estimated at over ten billion light years - almost anything seems possible, except perhaps the chance of looking in the right direction when an alien signal happens to be coming our way. So, compared with SETI's mission, our current predicament seems positively promising. First, we can be reasonably confident that the aliens exist; and second, we know roughly where they live - somewhere in the ocean and, very possibly, in this particular sea. But even if they turned out to live at the opposite pole, we'd still have narrowed it down. They can't leave the oceans, and a strong sound wave sent from the Arctic can still be heard on the other side of Africa, which gives us good grounds for hope. But there's an even more decisive factor.

We're already in contact

. We've been sending messages into their habitat for decades. Regrettably, those messages have brought with them destruction, so the yrr haven't bothered with ambassadors or diplomacy: they've launched straight into war. From our point of view, that's tiresome, but for the moment we should set aside our negative feelings and consider the onslaught as a kind of opportunity.'

âAn opportunity?' echoed Peak.

âYes, we have to see it for what it is - a message from an alien life-form that can help us discover how it thinks.' She placed her hand over a stack

of plastic files. âI've outlined the basis of our approach in these packs. But if any of you thinks this is going to be easy, I'm going to have to disillusion you. No doubt you'll have been wrestling with the question as to what kind of creature could be sending us the seven plagues. I guess you're familiar with

Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T., Alien, Independence Day, The Abyss, Contact

and so on, and you'll probably be expecting either monsters or saints. Take the ending of

Close Encounters

. A superior intelligence descends from space to lead the worthy to a better, brighter future. For lots of people, that's a comforting thought, but doesn't it remind you of something? Exactly! There's a strong religious current beneath the surface of these movies. To some extent, the same could be said about SETI. The trouble is, it blinds us to how radically different an alien intelligence is likely to be.'

Crowe gave them time to digest what she was saying. She'd thought long and hard about the best way to approach the project, and she knew that she wouldn't make progress until the myths had been debunked.

âMy point is that science fiction never engages with the true alienness of non-human civilisations. Sci-fi's extra-terrestrials are grotesquely exaggerated projections of human hopes and fears. The aliens in

Close Encounters

symbolise our longing for a lost Eden. They're essentially angels, and that's their function: a few chosen people are guided to the light. Of course, no one's interested in whether these aliens have their own culture. They only exist to serve basic religious notions. Everything about them is human, because that's how humans would like aliens to be. Even their appearance - glowing white light and what have you - has been choreographed to suit us. The same goes for the aliens in

Independence Day

. They're not really

alien

, in so far as they just live up to our notions of evil. The movies don't allow their aliens to be genuinely different. Good and evil are human concepts, and stories that try to do without them seldom catch on. It's hard for us to accept that our values aren't shared by other civilisations, but it's a problem we face all the time. Every human culture finds aliens on its doorstep - or just across the border. To communicate with an alien intelligence, we have to understand that. It's more than likely that we won't have any common values; and if our senses aren't compatible, we may not be able to communicate in any conventional way.'

Crowe handed the stack of files to Johanson, who was sitting next to her, and asked him to pass them round the room.

âIf we want to think seriously about communicating with an alien civilisation, we can begin by imagining a state run by ants. Although ants are highly organised, they're not truly intelligent, but for the purpose of the exercise, let's imagine they are. In effect, we'd be dealing with a collective intelligence that sees nothing wrong with feasting on injured members of its species, that goes to war but doesn't understand our concept of peace, that sets no store by individual reproduction, and that treats the harvesting and consumption of excrement as a kind of sacred ceremony. We'd be trying to communicate with a collective intelligence that works in a completely different way from our own.

But it works!

Let's take this a step further. Suppose for a moment that we don't recognise alien intelligence, even when it comes our way. Leon, for instance, runs all kinds of tests because he wants to find out if dolphins are intelligent, but will he ever know for sure? Conversely, what would an alien intelligence think about us? The yrr are attacking us, but do they credit us with

intelligence?

Do you see what I'm driving at? We're not going to get any closer to understanding the yrr until we've dispensed with the idea that our system of values is the be-all and end-all of the universe. We have to cut ourselves down to size - to what we really are: just one among an infinite number of possible species, with no special claim to being anything more.'

Crowe noticed that Li was scrutinising Johanson's expression - as though she was trying to see inside his head. There were some interesting constellations on board, she thought. Then she caught Jack O'Bannon and Alicia Delaware exchanging glances, and knew that they were more than friends.

âDr Crowe,' said Vanderbilt, leafing through the pages of his file, âwhat would you say constitutes intelligence?'

It sounded like a trick question.

âA stroke of luck,' said Crowe.

â

Luck?

'

âIntelligence occurs when a host of different factors unite in a specific way. How many definitions do you want? Some people think intelligence is simply whatever is deemed valuable within a particular culture. According to some people, intelligence can be analysed by examining basic thought processes, while others try to measure it statistically. Then there's the question of origin: is intelligence inborn or acquired? At the beginning of the twentieth century it was postulated that intelligence

could be gauged by studying an individual's ability to master certain tasks. That's what modern-day experts base their ideas on when they define it as the ability to adapt to the demands of a changing environment. In their view, intelligence is acquired, not genetically determined, but others argue that it's an innate part of being human - an inborn capacity that helps us adjust our thinking to new situations. If you take that line, then intelligence is the ability to learn from experience and to adapt to your surroundings. And then there's my personal favourite: intelligence is asking what intelligence means.'

Vanderbilt nodded slowly. âI see. So you don't really know.'

Crowe grinned. âI hope you won't mind my using your T-shirt to illustrate an example, Mr Vanderbilt, but it's unlikely we'd be able to judge a being's intelligence from its appearance.'

Laughter rippled through the room and ebbed away. Vanderbilt was staring at her. Then he grinned. âI dare say you're right.'

Â

Once the ice had been broken, the meeting gathered pace. Crowe outlined the next steps. During the past few weeks she'd worked out a basic strategy with the help of Murray Shankar, Judith Li, Leon Anawak and some of the guys from NASA. It was based on the limited number of attempts to make contact that had been conducted in the past.

âSpace makes things easy for us,' Crowe explained. âYou can send out huge packets of data in the microwave spectrum. Light is easy to spot and it travels at three hundred thousand kilometres per second. You don't need any cables or wires. It's a different story under water. Water molecules absorb the energy of short-wave signals, while for a long-wave signal you'd need enormous antennae. Light waves

can

be used to communicate under water, but only over relatively short distances. So that leaves us with sound. But sound comes with its own particular drawback - the echo effect. Sound waves get deflected all over the place, and that leads to interference. The message would overlap with itself and become unintelligible. To get round that, we need a special modem.'

âWe borrowed the principle from marine mammals,' said Anawak. âDolphins use it. They've essentially invented a way of outsmarting echoes and interference. They sing.'

âI thought that was whales,' said Peak.

âWhen we talk about whalesong, we only mean it sounds as though they're singing,' explained Anawak. âMusic may not exist to them as a

concept. In this instance singing means constantly modulating the frequency and pitch of the noise. There are two advantages. You get round the problem of interference, and you increase the amount of data you're able to transmit. We'll be using a singing modem. We can get it to transmit thirty kilobytes of information over a distance of three kilometres. That's a lot of data - half the capacity of an ISDN line. It's enough to beam out high-resolution images.'

âSo what are we going to say?' asked Peak.

âThe laws of physics are expressed in mathematics,' said Crowe. âThey're the cosmic code that gave rise to consciousness in the first place, allowing humanity to understand math. Math is life's way of explaining its own origins. It's the only universal language that any intelligent being subject to the same physical conditions would understand. It's the language we'll use.'

âHow? Are you going to make them do sums?'

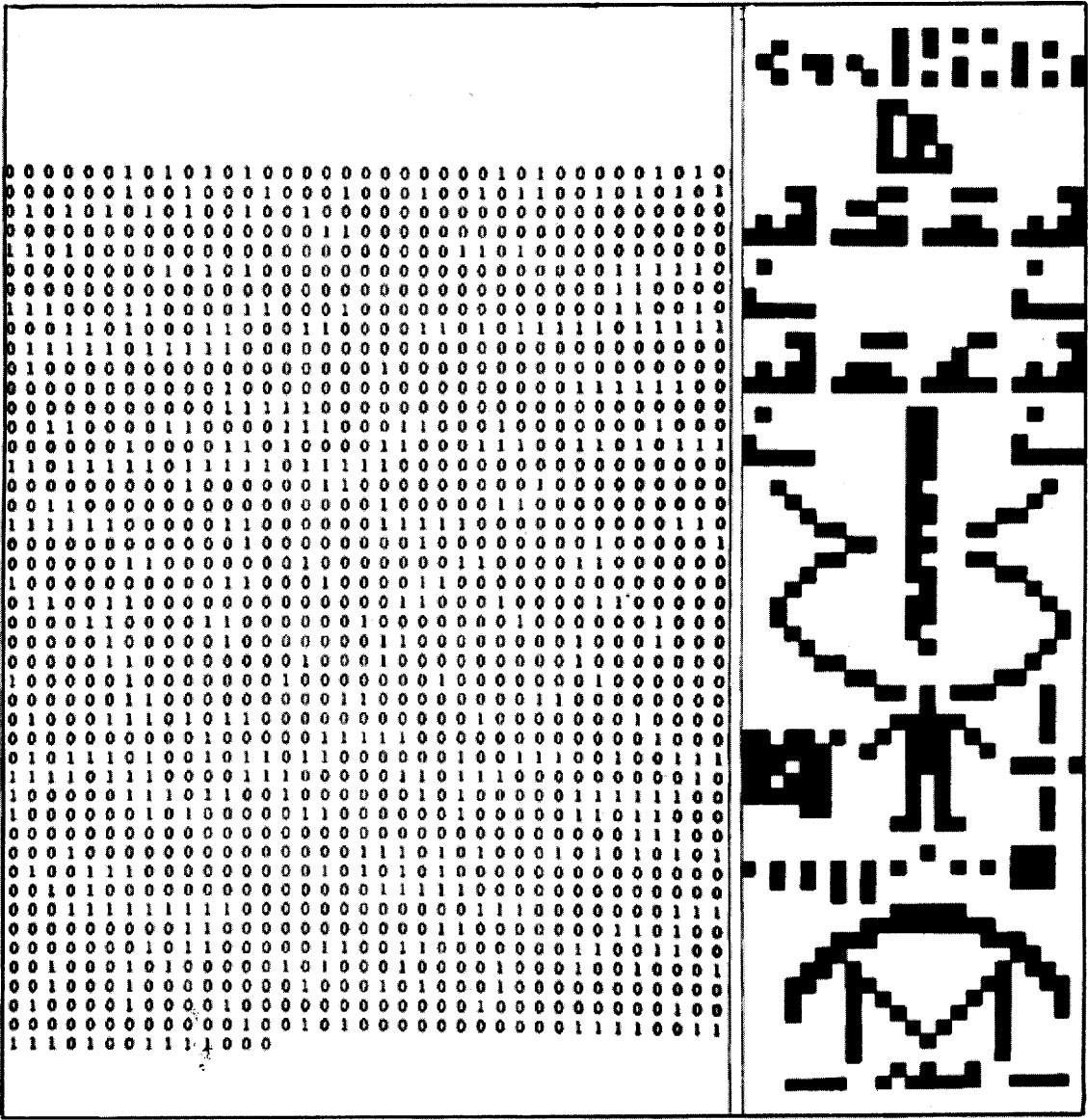

âNo. We're going to express our thoughts in math. In 1974, SETI fired a powerful radio wave from Earth towards a globular cluster in the constellation of Hercules. We sent 1679 characters, all expressed in binary pulses - ones and zeros, like the dots and dashes of Morse code. A mathematician would know what to do with the number 1679 because it's the unique product of two prime numbers, 23 and 73, numbers only divisible by one and themselves. In other words, the basics of our numerical system were contained within the structure of the message. The 1679 pulses separate into 73 columns, each containing 23 characters. Well, a little mathematics goes a long way, and if you turn the dots and dashes into black and white blocks, lo and behold, a pattern will emerge.'

She held up a diagram on a sheet of paper. It resembled a pixelated computer printout. Parts of it looked abstract, but there were some clearly identifiable shapes.

âThe top lines represent the numbers one to ten and contain information on our decimal system. Below that are the atomic numbers of five chemical substances: water, carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and phosphorus. All five substances are crucial to life on this planet. The message continues with extensive information about the biochemistry of the Earth, with formulae for our DNA bases and sugars, the structure of the double helix and so on. The final third of the message shows an image of the human form, linked directly to the representation of DNA, from which the recipient should be able to deduce the nature of evolution on Earth. Our units of size wouldn't mean anything to an alien intelligence, so the wavelength of the message was used to convey the average human height. Following on from there is a diagram of our solar system, and then, to round it all off, we've got details of the appearance, dimensions and design of the Arecibo radio telescope from which the message was sent.'

âA polite invitation for them to visit our planet and eat us alive,' said Vanderbilt.

âThat was exactly what concerned the authorities. But we've always had an answer to that: the aliens don't need our invitation. Humanity has been sending radio waves into space for decades. All our radio traffic goes up there - including all the chatter from intelligence agencies. You don't need to decode those signals to know that they must have been sent by a civilisation with technology.' Crowe put down the diagram. âWe expect the Arecibo message to take twenty-six thousand years to reach its destination, so it'll take fifty-two thousand before we receive a reply. You'll be pleased to hear that our underwater message will be faster.

We're going to proceed in stages. Our first communication will be straightforward. You were partly right, Major Peak - we'll be sending them two sums. If they're sporting, they'll answer. The first exchange is designed to prove the existence of the yrr and to gauge our chance of initiating dialogue.'

âWhy would they bother to reply?' asked Greywolf. âThey know enough about us already.'

âWell, they may know some things, but they won't necessarily know the essential point: that we're an intelligent species.'