The Sword And The Olive (35 page)

Read The Sword And The Olive Online

Authors: Martin van Creveld

Meanwhile, not being informed as to the true state of its own defenses, the Israeli public panicked before the twelve or so Arab divisions surrounding them. The feeling in Israel during those awful days was as if the world was coming to an end and a second Holocaust just around the corner. Full mobilization caused the economy to come to a near halt and men up to middle age inclusive to disappear from the streets. Steeling themselves to losses, the Israelis prepared three times as many hospital beds (14,000) than were eventually needed; meanwhile, fearing that the regular burial services would break down, Tel Aviv parks were ritually designated as cemeteries. Prime Minister Eshkol’s May 28 radio address did not help; he used IDF-ese and began to stutter as a result.

95

A “Government of National Unity” was set up, with Begin and one of his cronies as ministers without portfolio. More important, Eshkol—who had once referred to the one-eyed general as Abu Jilda, after an Arab bandleader of the 1930s—was forced by public opinion to relinquish the defense portfolio and entrust it to Dayan (a lasting blow to his self-confidence). Dayan spent the few remaining days holding speeches and touring the front. As Weizman told Eshkol at the time, the IDF was perfectly capable of winning the war without him.

96

Yet when victory came he would garner much of the glory.

95

A “Government of National Unity” was set up, with Begin and one of his cronies as ministers without portfolio. More important, Eshkol—who had once referred to the one-eyed general as Abu Jilda, after an Arab bandleader of the 1930s—was forced by public opinion to relinquish the defense portfolio and entrust it to Dayan (a lasting blow to his self-confidence). Dayan spent the few remaining days holding speeches and touring the front. As Weizman told Eshkol at the time, the IDF was perfectly capable of winning the war without him.

96

Yet when victory came he would garner much of the glory.

To sum up, the IDF was confident in its power and extremely aggressive. Led by Rabin, it had done what it could to provoke the Syrians, even though by June 1967 it was at least one year since the latter had desisted from their attempt to divert the sources of the Jordan. Why Nasser chose to support Damascus at the time and in the form that he did also remains a mystery, but it very likely had something to do with his fear that Israel was about to develop nuclear weapons. When the crisis came it took the Israelis by surprise. From Ben Gurion on down, at least some of Israel’s leaders were left in the dark concerning the IDF’s true strength. If the real and alleged number of tanks is any indication, the underestimate may have been as much as 60 percent; one source even has Rabin tell the Cabinet that, in number of troops, Israel could match Egypt and Syria combined.

97

Still more important was the effect on the Israeli public and the IDF rank and file—with the welcome result that during the tense weeks that preceded the war both thought of nothing but fighting for their very lives. As it turned out, fighting for its very life is precisely what the IDF would do.

97

Still more important was the effect on the Israeli public and the IDF rank and file—with the welcome result that during the tense weeks that preceded the war both thought of nothing but fighting for their very lives. As it turned out, fighting for its very life is precisely what the IDF would do.

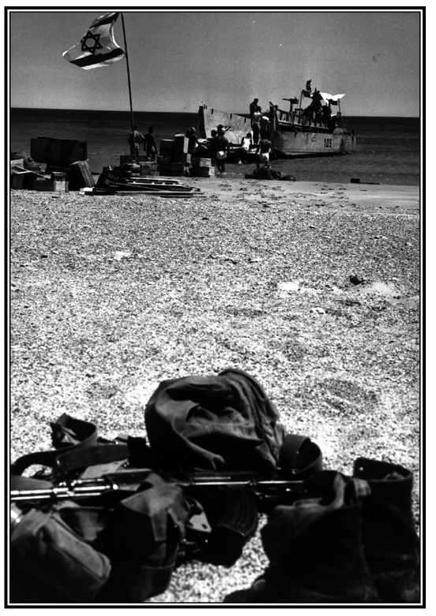

The Apogee of Blitzkrieg: Israeli landing craft unloading supplies at Sharm al-Sheikh, June 1967.

CHAPTER 11

THE APOGEE OF BLITZKRIEG

T

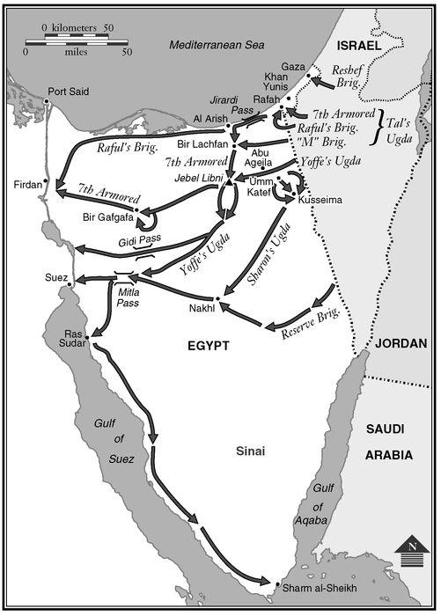

HE IDF HAD NOT been idle since 1956, building up a formidable order of battle, and neither had its Arab enemies. In 1967, as eleven years earlier, the strongest country was Egypt. Egypt’s air force was deployed in some nineteen airfields, most located west of the Suez Canal. It had 385 combat aircraft, all of them Soviet-built (in contrast to 1956, when some were British) and including MIG-17, MIG-19, and MIG-21 fighters; Su-7 attack aircraft; as well as T-16 medium and Il-28 light bombers. As in the IAF, some aircraft were more modern than others, but none were obsolete. They provided cover to Egypt’s forces in the Sinai Peninsula: approximately 100,000 men armed with 900 tanks, 200 assault guns, and 900 artillery barrels. As in 1956 there was a Palestinian division, the 20th, in the Gaza Strip. As in 1956, too, the Egyptian formations were deployed along the main roads leading into the Sinai with an eye to blocking them—forming a “shield” with a “sword” behind ready to counterattack (see Map 11.1).

HE IDF HAD NOT been idle since 1956, building up a formidable order of battle, and neither had its Arab enemies. In 1967, as eleven years earlier, the strongest country was Egypt. Egypt’s air force was deployed in some nineteen airfields, most located west of the Suez Canal. It had 385 combat aircraft, all of them Soviet-built (in contrast to 1956, when some were British) and including MIG-17, MIG-19, and MIG-21 fighters; Su-7 attack aircraft; as well as T-16 medium and Il-28 light bombers. As in the IAF, some aircraft were more modern than others, but none were obsolete. They provided cover to Egypt’s forces in the Sinai Peninsula: approximately 100,000 men armed with 900 tanks, 200 assault guns, and 900 artillery barrels. As in 1956 there was a Palestinian division, the 20th, in the Gaza Strip. As in 1956, too, the Egyptian formations were deployed along the main roads leading into the Sinai with an eye to blocking them—forming a “shield” with a “sword” behind ready to counterattack (see Map 11.1).

From north to south, 7th Infantry Division was at Al Arish, 2nd Infantry Division in the Abu Ageila-Umm Katef area, and 6th Infantry Division at Kuntilla; besides the usual artillery regiment, each unit was reinforced by an armored battalion. On the central axis, 3rd Infantry Division stood behind 2nd Infantry Division in reserve. It was backed up by two armored formations, 4th Armored Division at Bir Gafgafa and “Force Shazly”—actually a heavily reinforced brigade—far south at Nakhl. During the days just before the Six Day War, the Palestinians in Gaza exchanged fire with the Israelis; of the remaining Egyptian forces only Force Shazly could have been quickly redeployed for advancing into southern Negev Desert. Even this threat does not seem to have caused Rabin any loss of sleep, for the forces he allocated for the defense of Elat were absolutely minimal. As he later wrote, “We were informed about Egypt’s defensive plans ... but we did not have their offensive ones, if any.”

1

1

What was true of the Egyptians also seems to have applied to the Jordanians (see Map 11.2). King Hussein having been forced into the confrontation by public opinion,

2

his army found itself geographically well positioned to cut Israel in half; however, with an overall strength of 55,000 men it was much too weak to accomplish anything of the sort. The air force had only twenty-one subsonic, 1950s-vintage Hawker Hunter fighters (on the eve of the war six new F-104s were spirited to Turkey)

3

and no bombers of any kind. The ground forces, with 100 artillery pieces and some 300 tanks, were reasonably well armed; still they could not match the IDF, which had received more advanced versions of the same tanks (M-48 Pattons and Centurions). Nine of eleven brigades were deployed in the West Bank in “a forward defense posture to ensure that not an inch of the Holy Land was abandoned without a fight”;

4

of those, again the two armored ones were stationed in the rear, that is, the Jordan Valley, with the idea of forming an operational reserve and counterattack. As already mentioned, when the crisis erupted the Jordanians allowed an Egyptian general to take charge of their army and also admitted two Egyptian commando battalions; on the night of June 4-5 they were further reinforced by an Iraqi armored brigade (the 8th), which entered the country from the east. Coming under attack by the IAF, however, it never even approached the River Jordan, let alone crossed it.

2

his army found itself geographically well positioned to cut Israel in half; however, with an overall strength of 55,000 men it was much too weak to accomplish anything of the sort. The air force had only twenty-one subsonic, 1950s-vintage Hawker Hunter fighters (on the eve of the war six new F-104s were spirited to Turkey)

3

and no bombers of any kind. The ground forces, with 100 artillery pieces and some 300 tanks, were reasonably well armed; still they could not match the IDF, which had received more advanced versions of the same tanks (M-48 Pattons and Centurions). Nine of eleven brigades were deployed in the West Bank in “a forward defense posture to ensure that not an inch of the Holy Land was abandoned without a fight”;

4

of those, again the two armored ones were stationed in the rear, that is, the Jordan Valley, with the idea of forming an operational reserve and counterattack. As already mentioned, when the crisis erupted the Jordanians allowed an Egyptian general to take charge of their army and also admitted two Egyptian commando battalions; on the night of June 4-5 they were further reinforced by an Iraqi armored brigade (the 8th), which entered the country from the east. Coming under attack by the IAF, however, it never even approached the River Jordan, let alone crossed it.

Judging by their subsequent behavior, the Syrians were even less offensive-minded than the Jordanians.

5

As mentioned earlier, in 1948 two different Syrian forces had penetrated perhaps two miles into Erets Yisrael before being defeated and contained at Degania and Mishmar Ha-yarden, respectively. Since then they had often clashed with the IDF by firing at various Israeli military and civilian targets along the border. Not once did they try to cross that border, however, and indeed during the mid-sixties Damascus often claimed that the way to deal with the Zionist entity was not by means of conventional warfare but of guerrilla warfare on the lines of Algeria and Vietnam.

6

By supporting terrorist activities inside Israel, Syrian intelligence did its bit to raise tensions, thus helping to trigger the process that led to war.

5

As mentioned earlier, in 1948 two different Syrian forces had penetrated perhaps two miles into Erets Yisrael before being defeated and contained at Degania and Mishmar Ha-yarden, respectively. Since then they had often clashed with the IDF by firing at various Israeli military and civilian targets along the border. Not once did they try to cross that border, however, and indeed during the mid-sixties Damascus often claimed that the way to deal with the Zionist entity was not by means of conventional warfare but of guerrilla warfare on the lines of Algeria and Vietnam.

6

By supporting terrorist activities inside Israel, Syrian intelligence did its bit to raise tensions, thus helping to trigger the process that led to war.

At that time the Syrian armed forces had 65,000 men. The air force had slightly under 100 Soviet-built combat aircraft and was judged capable of carrying out “simple” operations; the ground forces consisted of the equivalent of ten brigades (including two armored and two mechanized) with 300 tanks and 300 artillery barrels.

7

Three infantry brigades occupied the slopes; three more, plus the two armored and one mechanized brigades, were stationed on the plateau itself, with Kuneitra, on the road to Damascus, as their main base. In his 1966 annual report to London, the British military attaché wrote that he “shuddered to think” what the army’s “proletarian” officers and mostly “illiterate” rank and file would do with the advanced equipment at their disposal.

8

7

Three infantry brigades occupied the slopes; three more, plus the two armored and one mechanized brigades, were stationed on the plateau itself, with Kuneitra, on the road to Damascus, as their main base. In his 1966 annual report to London, the British military attaché wrote that he “shuddered to think” what the army’s “proletarian” officers and mostly “illiterate” rank and file would do with the advanced equipment at their disposal.

8

MAP 11.1 THE 1967 WAR, EGYPTIAN FRONT

Preparing for the worst case—a simultaneous clash with all these forces—the IDF had distributed its forces between its Southern, Central, and Northern Commands.

9

Facing the Egyptians, Brig. Gen. Yeshayahu Gavish had under him three

ugdas

with, from north to south, three, two, and four brigades. Of the nine, five were armored, three consisted of more or less motorized infantry (the available vehicles ranged from World War II half-tracks to civilian trucks), and one of heliborne paratroopers; in addition Gavish had three independent brigades (including one armored) standing by as an operational reserve. Central Command, under Brig. Gen. Uzi Narkis, had five brigades. Of these, one (the “Jerusalem Brigade”) was already in Jerusalem; three were in the coastal plain and were brought up to participate in the battles around Jerusalem; one was to attack Nablus from the west. Finally, Brigadier General Elazar’s Northern Command was split in two. Deployed in the Valley of Esdraelon and facing the Jordanians was an

ugda

under Brig. Gen. Elad Peled with one armored, one mechanized, and one infantry brigade. Left to face the Syrians under Brig. Gen. David Lanner were two infantry and one mechanized brigades. However, the IDF did not expect serious trouble on that front. On June 4 Dayan told a frustrated Elazar to “resign himself ” to the fact that the war would be waged “against Egypt and not against others”; he even doubted whether the Syrians would enter the war at all.

10

9

Facing the Egyptians, Brig. Gen. Yeshayahu Gavish had under him three

ugdas

with, from north to south, three, two, and four brigades. Of the nine, five were armored, three consisted of more or less motorized infantry (the available vehicles ranged from World War II half-tracks to civilian trucks), and one of heliborne paratroopers; in addition Gavish had three independent brigades (including one armored) standing by as an operational reserve. Central Command, under Brig. Gen. Uzi Narkis, had five brigades. Of these, one (the “Jerusalem Brigade”) was already in Jerusalem; three were in the coastal plain and were brought up to participate in the battles around Jerusalem; one was to attack Nablus from the west. Finally, Brigadier General Elazar’s Northern Command was split in two. Deployed in the Valley of Esdraelon and facing the Jordanians was an

ugda

under Brig. Gen. Elad Peled with one armored, one mechanized, and one infantry brigade. Left to face the Syrians under Brig. Gen. David Lanner were two infantry and one mechanized brigades. However, the IDF did not expect serious trouble on that front. On June 4 Dayan told a frustrated Elazar to “resign himself ” to the fact that the war would be waged “against Egypt and not against others”; he even doubted whether the Syrians would enter the war at all.

10

Having blocked the Straits of Tyran on May 23, Nasser and his allies seem to have been content to make warlike noises and wait. Not so Israel, which, owing to its system of mobilization, could not afford to do the same—and where people believed themselves in mortal danger. Arguing that time would enable the Egyptians to reinforce their hold on the Sinai, many of the

alufim

on the General Staff pressed for action (some calculated that each passing day would result in two hundred additional IDF casualties).

11

Still more eager to go was the chief of the General Staff, Ezer Weizman. A former air force commander, he feared lest waiting would compromise the plan for a first strike against the Egyptian airfields on which he and his successor, Brig. Gen. Mordechai Hod, had worked for so long. Roaring and bellowing, as was his wont, he went so far as to throw his epaulets on the table in front of a vacillating Eshkol,

12

this probably being the closest thing to a coup that Israel has ever experienced.

alufim

on the General Staff pressed for action (some calculated that each passing day would result in two hundred additional IDF casualties).

11

Still more eager to go was the chief of the General Staff, Ezer Weizman. A former air force commander, he feared lest waiting would compromise the plan for a first strike against the Egyptian airfields on which he and his successor, Brig. Gen. Mordechai Hod, had worked for so long. Roaring and bellowing, as was his wont, he went so far as to throw his epaulets on the table in front of a vacillating Eshkol,

12

this probably being the closest thing to a coup that Israel has ever experienced.

Faithful to its strategic approach, the IDF under Rabin had developed a number of plans, all of which envisaged taking the offensive at the earliest possible moment.

13

Though there was never any doubt about Egypt being the main enemy, initially it was not clear whether the attack against it would be limited, aiming at the occupation of the Gaza Strip and/or Sharm al-Sheikh, or full-scale, smashing the Egyptian army and overrunning the entire Sinai Peninsula; once the latter had been adopted it was still necessary to decide whether the main effort would be made by the northern

ugda

breaking through to Al Arish or the central one driving through ground the Egyptians regarded as impassable to attack the rear. There was also some debate whether to use the opportunity to launch an attack against Jordan. The events at Samua in 1966 demonstrated to the General Staff how easily the IDF could overrun the West Bank,

14

thus setting right the “historical error” of 1948. That idea, however, was rejected. In fact, for hours after the Jordanians opened fire on June 5, the government of Israel was still sending messages calling for mediation in an attempt to avoid a large-scale confrontation with its neighbor to the east.

15

13

Though there was never any doubt about Egypt being the main enemy, initially it was not clear whether the attack against it would be limited, aiming at the occupation of the Gaza Strip and/or Sharm al-Sheikh, or full-scale, smashing the Egyptian army and overrunning the entire Sinai Peninsula; once the latter had been adopted it was still necessary to decide whether the main effort would be made by the northern

ugda

breaking through to Al Arish or the central one driving through ground the Egyptians regarded as impassable to attack the rear. There was also some debate whether to use the opportunity to launch an attack against Jordan. The events at Samua in 1966 demonstrated to the General Staff how easily the IDF could overrun the West Bank,

14

thus setting right the “historical error” of 1948. That idea, however, was rejected. In fact, for hours after the Jordanians opened fire on June 5, the government of Israel was still sending messages calling for mediation in an attempt to avoid a large-scale confrontation with its neighbor to the east.

15

As the slide toward war continued, much depended on making sure the United States would not object, as it had in 1956. During the last week of May, there was a flurry of diplomatic activity as Foreign Minister Abba Eban attempted to hold the three Western powers (United States, Great Britain, and France) to their 1957 promise to open the Straits of Tyran if blocked by Egypt.

16

He failed, but at any rate his highly publicized visits reinforced the Israeli public’s feeling that it was alone and thus strengthened its determination to fight for its life—probably the most decisive factor in the war.

16

He failed, but at any rate his highly publicized visits reinforced the Israeli public’s feeling that it was alone and thus strengthened its determination to fight for its life—probably the most decisive factor in the war.

Other books

Winter Wedding by Joan Smith

The Headmaster's Dilemma by Louis Auchincloss

Jala's Mask by Mike Grinti

Hopper by Tom Folsom

Fool Me Twice by Mandy Hubbard

Smoke and Shadows by Victoria Paige

Lonesome Bride by Megan Hart

Time Eternal by Lily Worthington

Ghost Cat - Thelma's Dilemma by Carol Colbert

Alchemy and Meggy Swann by Karen Cushman