The Thing with Feathers (19 page)

Read The Thing with Feathers Online

Authors: Noah Strycker

In recent years, chickens have been bred to grow ever faster and bigger. Today’s six-week-old chicken is six times heavier than an equivalent breed in 1957 and has about 10 percent more breast meat. But breeders haven’t focused much on personality; as chickens have grown in size, they’ve also become more aggressive. After all, chickens were first domesticated for cockfighting, not food.

Randall noted that for some reason the color red caused his chickens to go berserk. This fact was already well documented by other chicken farmers, who occasionally watched in horror as their birds pecked each other to death. When a chicken bleeds, other birds in the coop become fascinated by the bright red wound and peck at it repeatedly, sometimes inflicting serious damage.

Chickens have incredibly well-defined color vision, even better than ours. Unlike, say, bulls—which are color-blind and chase the matador’s cape because it’s twitching, not because it’s red—chickens nurse a real lust for blood. The color red incites them to violence.

Other farmers had tried replacing the regular lightbulbs in their chicken coops with red ones, which mitigated some of the chickens’ bad behavior. They theorized that the red light caused red objects—combs, wattles, blood—to blend in better, making

it harder for the birds to single them out. But the darker light was difficult for humans to work in, so most farms switched back to regular illumination and trimmed their chickens’ beaks with a hot knife, hoping to blunt them enough to prevent serious chicken-on-chicken injuries.

Randall pondered all this while he spent eight years cooped up in the software industry. Finally, he just couldn’t stand it anymore and sold his business for millions, headed west, and founded a new company, called Animalens, to design red contact lenses for chickens.

That’s right. Tiny red contacts. For chickens. Rose-colored glasses didn’t work; he’d already tried it. The frames wouldn’t stay on the chickens’ round heads.

Randall believed he had found the perfect recipe for success. When the birds wore his contacts, they’d see their surroundings bathed in a soft red glow, as if the coops were wired with red lights. The birds would be calmer, more productive, and less apt to kill one another. Randall believed that the lenses could save poultry growers hundreds of millions of dollars per year through increased productivity and decreased feed consumption. Animalens contacts hit the market in 1989, priced at 20 cents per pair, or 15 cents apiece for large orders.

The idea wasn’t as outlandish as it sounds, especially considering the weird breeds produced by the chicken industry. We’ve got the frizzle, a chicken with curly, mutated feathers; the phoenix, which grows tail streamers up to twenty feet long; the silkie, a fluffy cotton ball on legs; and the Transylvanian naked neck, sometimes called the turken for its wild resemblance to a turkey, with bare skin from the shoulders up. Why not a chicken that always sees red?

Initially, large-scale chicken operations were intrigued. Chickens wearing Randall’s red contact lenses did seem to

behave more calmly, saving an anticipated third of a penny for each egg produced. Considering that one Wisconsin-based chicken farm now produces 7.5 million eggs

per day

, the cost savings would be substantial for high-volume egg plants.

But farmers hated to hold each bird’s head steady while they tried to jab contacts into millions of little eyeballs, and installing the tiny pieces of plastic was harder than Randall had let on. The lenses were supposed to stay in for life, but they kept falling out or, worse, causing physical damage. Chickens wearing contacts developed severe eye irritations and actually became more stressed. One investigation showed that birds wearing contacts developed bigger heart muscles, perhaps to cope with the anxiety of having irritated eyes and no fingers with which to soothe them.

Ultimately, the red contacts did little to reduce operating costs, and animal-rights groups were mad as wet hens about their effects on the birds’ health. By the mid-1990s, the company had folded.

Randall Wise thus learned a worthy lesson: Messing with basic social instinct is a risky business. Even if pecking orders are confusing to us, for chickens they are a matter of life and death. Aggression and dominance may not always be desirable, but they do serve a purpose. Trying to erase those characteristics might just cause more problems than it solves—in a chicken farm and in the world in general. Sometimes, it’s better to let a natural order sort itself out.

May the best chicken win.

cache memory

HOW NUTCRACKERS HOARD INFORMATION

T

hings were not going well for thirty-five-year-old scouting agent William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) on August 22, 1805. He was exploring the rugged Salmon River canyon, in what is now northern Idaho, on a typically harrowing day: A hunter from his group had just returned from a close run-in with some Native Americans, the terrain was brutally steep and rugged, and he didn’t know where he was going. But sometime that afternoon the explorer noticed a bird interesting enough to record in his now famous journal:

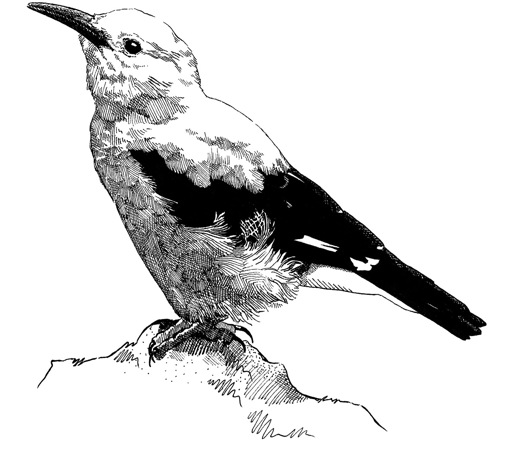

“I saw to day [a] bird of the woodpecker kind which fed on Pine burs it’s Bill and tale white the wings black every other part of a light brown, and about the size of a robin.”

He didn’t have time to elaborate (or punctuate) further, but his partner, Meriwether Lewis, described the same bird less than a year later with better detail and leisure, while waiting patiently for snow to melt in the Bitterroot Mountains on the expedition’s eastward return journey. Lewis correctly surmised that Clark’s black-and-white bird wasn’t a woodpecker but a corvid—related to crows and jays.

“Since my arrival here I have killed several birds of the corvus genus,” Lewis wrote. “It is about the size and somewhat the form of a Jaybird . . . it resides in the Rocky Mountains at all seasons of the year, and in many parts is the only bird to be found.”

Lewis’s specimens of this bird were eventually deposited in the Peale Museum in Philadelphia. Alexander Wilson included an illustration of the new bird in his 1811 book

American Ornithology

, calling it Clark’s crow, with proper credit to the

discoverer. (To be fair, Lewis was honored with his own namesake, the Lewis’s woodpecker, which he had described in his journal the day before writing about the new crow-like species.) The name stuck but was later modified, and we are left today with an explorer’s legacy: the Clark’s nutcracker.

If you’ve spent time in the rugged mountains of western North America, you’ve probably heard and seen nutcrackers. The birds are easy to identify: big, black and white overall, with flashing white wings and tail patches in flight and a cool gray body. No other bird looks anything like a nutcracker. And they make themselves obvious, perching on exposed treetops and flying around high meadows, searching boldly for their next meal. Particularly fearless nutcrackers are sometimes called “camp robbers” for their habit of stealing food from unwary backpackers. Even if you hiked blindfolded into the mountains, you’d still know the nutcrackers were there. The characteristic loud

kkrrraaaaaaack

provides a running sound track in high-elevation pine forests, where the noise echoes off craggy peaks just as it did hundreds of years ago.

Lewis and Clark gave a fairly accurate description of nutcrackers. Lewis observed that they remain in the high mountains “at all seasons of the year,” even while most other birds migrate south or to lower elevations for the winter. These days, one of the best ways to see a Clark’s nutcracker is to visit a ski resort during peak season, where the birds often hang around high-elevation parking lots looking for handouts. But those early pioneers probably didn’t realize that nutcrackers also, improbably,

nest

in the winter, laying their eggs during the brutal snowstorms of late January and early February. While the Lewis and Clark expedition wintered by the muddy mouth of the Columbia River, waiting for summer to arrive so they could head home, the nutcrackers they’d observed in Idaho were

happily raising chicks high up in the mountains. By the time the snow had melted enough for the expedition to traverse east in May and June, the young nutcrackers had already fledged.

Not many other birds nest on mountaintops in the middle of winter, and for good reason. It’s cold and stormy up there. Food is also scarce in the high country during the winter, and what little food may be left is difficult to find under packed snow. That’s the main reason most mountain birds spend their winters in warmer climates—they’d starve if they didn’t migrate. But nutcrackers are smart. They’re related to the intelligent crows and ravens, and they’ve learned a trick to not only survive but thrive in the mountains during the cold season. The trick is pretty simple: They do what Lewis and Clark did.

Those great explorers, when Thomas Jefferson charged them to find a route across North America, knew that they were in for an unpredictable adventure, so they loaded up on supplies. Lewis reportedly spent $2,324 on gear—equivalent to about $50,000 today—for his thirty-man crew. The packing list included, among many other things, twenty-five hatchets, forty-five flannel shirts, five hundred rifle flints, thirty-five oars, an iron corn mill, eleven hundred doses of emetic (to induce vomiting in case of poison), twenty pounds of glass beads, a four-volume dictionary, three bushels of salt, and 193 pounds of “portable soup.” One of the largest sections of the list was titled “presents for Indian tribes encountered.” Every expedition marches on its stomach, and Lewis made sure that the Corps of Discovery would be well supplied to traverse the wilderness. He figured they could trade trinkets with the locals when hunting food became difficult.

Nutcrackers do the same thing to survive cold winters at high elevations: They stock up. The birds have a specialized diet of pine seeds, which are easy to find when cones ripen in

summer and fall. But the cone crop is seasonal, so Clark’s nutcrackers must cache massive quantities of pine seeds to eat during the winter and spring, when cones are unavailable. Amazingly, they depend completely on these stored seeds throughout the nesting season. Nothing else is available during the stark, white winter. Storing food makes it possible for nutcrackers to stay in the mountains, and even raise their young, throughout one of the harshest times of the year.

Because nutcrackers have to store a lot of pine seeds to survive an entire winter, during the bountiful part of the year they are forced to become veritable cache machines. The birds begin working full-time when cones first ripen in July and continue to gather seeds throughout the late summer, fall, and early winter. To help them carry food, nutcrackers have developed a special pouch under their tongue that can hold up to about a hundred seeds at a time. They use their heavy bills to pry apart pinecones and load up on seeds until the pouch is full, then fly off to stash their harvest in the ground—sometimes several miles away from the source tree. Instead of hiding them all in the same place, nutcrackers divvy up their loot in lots of little caches, poking three or four seeds at a time into the soil.

And this is where nutcrackers transcend mere survival. In one fall season, a single nutcracker may store tens of thousands of pine seeds in as many as 5,000 different mini-caches. The birds don’t mark the spots, and there is no surface indication that something is buried below ground—in fact, the caches are often covered by snow when winter arrives. Nutcrackers may leave caches alone for nine months before returning to collect their contents, and they don’t use the same locations from one year to the next. Sometimes other critters dig up the seeds, and sometimes they spoil underground, so the birds generally cache more than they need; one side effect is that extra seeds

sprout, which helps the pine trees spread. Incredibly, hungry nutcrackers are able to locate most of their stashes through the winter.

It’s a radical mental feat: Nutcrackers somehow remember exactly where thousands of different clumps of seeds are buried without a single yellow sticky note, global-positioning-system waypoint, or silly mnemonic.

How do they do it?

—

WHEN NELSON DELLIS,

a twenty-eight-year-old former software developer from Miami, attempted to summit Mount Everest in 2011, he took along a pack of playing cards. Not for entertainment, exactly. Dellis had recently become involved in the cultish sport of memory games, and he wanted his brain to stay active while he climbed. During his ascent, he regularly sat down with the cards, carefully shuffled them, and spent a couple of minutes trying to memorize the order of the entire deck. According to habit, he kept track of how many seconds it took to flawlessly recall the fifty-two cards in sequence each time, and he noticed something odd: As he gained elevation, his recall times shrank. The concentration exercise was easier than expected in distracting and exhausting conditions, which encouraged Dellis. It was good to have a sharp mind; he was climbing to raise money for Parkinson’s research, after all, and, while chasing high-elevation dreams, he was also training for a different kind of challenge.