The Thing with Feathers (15 page)

Read The Thing with Feathers Online

Authors: Noah Strycker

This doesn’t mean that fear in birds isn’t learned behavior. Birds that are hunted regularly, such as waterfowl, are known to be more easily spooked, with greater flight distances, during the hunting season than they are in other months. Likewise, birds that are regularly exposed to predators are more wary than those that live in predator-free environments. They can learn fear from personal experience—and they can learn fear from their parents. One study of quail found that chicks born of fearful mothers but raised by calm foster parents grew up to be calm adults; in other words, their fearfulness was more affected by how they were raised than by their instincts (though the degree to which this was true was moderated by the genetics of their true parents).

Birds can also be conditioned to be less fearful. A study of robins on an island in New Zealand found that one generation after the eradication of rats from the island, the robins showed significantly less agitation when confronted with a model rat

than did a population of robins on a nearby island where rats still roamed free. In just that one generation, they’d been conditioned to live in a predator-free environment.

But these examples still don’t achieve the kinds of cerebral, high-road fears—such as long-term emotional stress, worry, and dread—that humans have. Can birds project into the future based on emotional memories? Do they have lingering, non-instinctual anxiety? This is still unanswered. There is an essential difference between anxiety and fear. Anxiety is a mood without an identifiable stressor, but fear is an immediate reaction to a threat; of the two, fear is much easier to study because its physical symptoms are obvious.

So in birds and in humans, fear itself is innate, but the timing of the response is often learned. When it comes to our instinctual reactions to danger, we are quite similar. But beyond that, it’s tough to know what birds are thinking, whether they have long-term worries.

Psychologists Susan Suarez and Gordon Gallup, Jr., neatly summed up the situation in a volume of the scientific textbook

Bird Behavior

. They allowed that birds experience emotions, just as people do, but pointed out that we don’t have a very good framework for them. “The concepts of fear and emotionality can only be meaningfully applied to birds,” they said, “when they are explicitly tied to events which would have adaptive significance under natural conditions”—the assumption being that birds

do

have some kind of emotions, just like us. Penguins have feelings, too.

—

IN SPRING AND FALL,

the sun rises and sets in Antarctica on a regular schedule. Days are brilliantly bright and nights are abysmally black.

In between, for a couple of months during summer, the sun refuses to go down; it roves around the sky in a tilted, counterclockwise circle, dipping close to the horizon in the wee hours but never quite touching. During my entire field season at Cape Crozier, I never saw one sunset, and never saw any stars. In winter, the opposite is true: Months pass without a single sunrise.

Penguins, like us, are tied to the sun. The birds are active during daylight, and they sleep at night. In winter, they migrate to more northern areas outside the zone of perpetual darkness.

But why?

It’s not like penguins can’t function around the clock. In the constant daylight of summer, penguins ditch their circadian schedule. They go on feeding trips that last for days. While I set an alarm to keep a twenty-four-hour rhythm, I noticed that the penguin colony still remained as active at midnight as it had been at noon, and that penguins took naps whenever they felt tired, snuggling down in a comfortable-looking flat spot against the ice at any hour. Forget New York—the real city that never sleeps is the penguin metropolis at Cape Crozier in midsummer.

When the sun begins to roll below the horizon in late summer, though, the penguins align their schedules with it. They rest at night, go to sea at dawn, and return by dusk. When winter arrives, they swim hundreds of miles north to escape the months of constant darkness.

For years, scientists assumed that, like humans, penguins can’t see well in the dark. That would certainly hamper penguins’ ability to eat during Antarctic winter, when the sun spends most of its time shining on the other half of the world. Fish may even be easier to catch at night because they have a harder time detecting their predators in darkness. If the

penguins could navigate after the sun went down, they might have an easier time finding food.

But recent research has shown that penguins can see in darkness just fine. Our global-positioning-system tags with temperature, pressure, and light sensors indicated that the birds are often catching fish between 50 and 100 meters beneath the surface, a depth that is always as gloomy as early night. Sometimes they successfully forage even deeper. Emperor penguins occasionally swim as deep as 500 meters—about a third of a mile below the surface—where they might as well have their eyes shut. We wouldn’t be able to function down there, but penguins apparently are able to pursue fish in near-total blackness.

So why do they avoid the dark? Perhaps it’s just more convenient to be active when the sun is up. Hunting fish is one thing; socializing must be more fun in daylight.

The scientists who published the depth studies proposed a different explanation. They suggested that fear of leopard seals and killer whales drives penguins out of the water at night. Yes, it might be easier to catch fish in the dark, but penguins would be at greater risk of being caught themselves—and as we know, penguins are terribly afraid of leopard seals. They will commute miles over land instead of swimming the same distance parallel to shore, just to avoid the risk of those gnashing teeth.

An ecology of fear could explain the penguins’ winter migration, too. Unlike most migratory birds, which commute between food-rich destinations, penguins travel to marginal feeding areas in the winter with

less

fish than the year-round, nutrient-rich waters surrounding the edge of the Antarctic continent. They could be avoiding bad weather or thick sea ice that blocks access to fishing grounds. But fear of predators lurking in the blackness could also drive penguins northward, where they would have some reassuring daylight during the darkest months.

It’s an interesting theory, and it could easily be true. I witnessed the brutal terror of leopard seals one late summer afternoon at Cape Crozier. A seal had been prowling up and down the beach, just offshore from the penguin colony, for a couple of hours. Groups of hunting penguins would go skipping away in a panic whenever they swam too close to it. The attack happened suddenly. A lone penguin wandered down to the shore, failed to take proper precaution when entering the water, and waded in without spotting the danger. In a microsecond, the seal darted forward, snapped its jaws shut, and began to thrash the unlucky bird like a Rottweiler with a chew toy.

No wonder penguins go to great lengths to avoid being caught. Leopard seals are known to play with their prey before eating it, and this one took about 20 minutes to consume his meal in stages, using his sharp incisors to skin the penguin raw. Gore streamed through the seal’s teeth; the wild-eyed, ugly gray head reared up like something from a horror movie, jaws snapping, blood saturating the freezing water, a chunk of the penguin’s gleaming rib cage dangling from a corner of its mouth. As I looked on, mesmerized and horrified, I couldn’t help thinking: If that bird had just been a little more careful, it would have escaped. Sometimes, even for penguins, a little fear can save your life.

beat generation

DANCING PARROTS AND OUR STRANGE LOVE OF MUSIC

W

hen Dr. Aniruddh Patel first watched the video of Snowball, as he later reported to

The New York Times

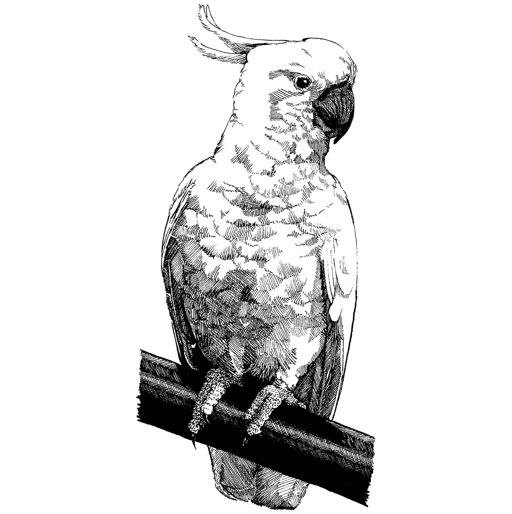

, his “jaw hit the floor.” Patel is an associate professor of psychology at Tufts University. Snowball is a sulphur-crested cockatoo—a type of large, white parrot with an ornate yellow crest, native to Australia—who likes to dance. In 2007, destiny, in the form of YouTube, brought the scientist and the dancing bird together.

If not for the Internet, Patel might never have met Snowball, who became a viral sensation after his owner in Indiana posted some impromptu footage of the bird’s dance moves. In the video, the cockatoo capers on the back of a chair to the Backstreet Boys song “Everybody (Backstreet’s Back).” He sways rhythmically, bobs his head up and down, energetically waves his feet, and twists in time with the sound track, looking for all the world like a teenybopper rocking out to those repetitive chords and bass lines. The video of the dancing bird had 200,000 hits in one week, and, at last count (five years later), more than five million views on just that one clip.

Patel had never seen anything like it. All his life, he’d been fascinated by music and the brain. When his Ph.D. adviser, the luminary American biologist E. O. Wilson, sent him to Australia to study ants in 1990, Patel tried to emulate his professor’s devotion to tiny insects. But one day he realized that he was more interested in the human biology of music. “You must follow your passion,” Wilson reportedly advised, so Patel gave up studying ants, left Australia, and dedicated himself to a groundbreaking thesis in language and music at Harvard University.

That launched him into the field of neurobiological research, which was just then beginning to focus on brain imaging; Patel subsequently published, among other things, a fascinating paper showing that our brains process language and music in much the same way.

Snowball also bounced around for a bit before making his mark in the world. Like many pet parrots, he rotated through a series of owners. Nobody knows where he came from or who raised him as a chick. When he was about six years old, he was adopted by a family in Indiana, who kept him for several years. But when the daughter in the family went off to college, Snowball began getting cranky and aggressive. The girl’s father decided that the parrot wasn’t getting enough attention, so he relinquished Snowball to a rescue shelter called Bird Lovers Only, which specializes in caring for neglected birds, also handing over Snowball’s favorite CD: the Backstreet Boys. “Just play it for him and watch what happens,” the owner suggested.

Irena Schulz, the founder of Bird Lovers Only and a former molecular biologist, about died laughing the first time she witnessed Snowball in action. Lots of parrots had passed through her shelter, but none had quite the same charm as this one. She made a short video of the dancing parrot, uploaded it for fun, and, well, things snowballed from there.

The quirky cockatoo was soon featured on

CBS Sunday Morning

,

The Morning Show with Mike and Juliet

,

Ellen

,

The Tonight Show with Jay Leno

,

Late Show with David Letterman

, NPR, BBC, CNN, National Geographic News, Animal Planet, a commercial for a new Taco Bell beverage, a commercial for Loka bottled water in Sweden, and three TV shows in Japan. Fans mailed in CDs from all over the world, hoping Snowball might dance to them (a German polka caught his

interest). Visitors started knocking on the door at Bird Lovers Only, purportedly to adopt a parrot, but really just to get a glimpse of the celebrity.

Schulz booked Snowball’s guest appearances as if she were a Hollywood agent. She recognized Snowball’s sudden fame as an opportunity to promote awareness for unwanted parrots, which often outlive their owners, and—why not?—to offer custom T-shirts, buttons, CDs, DVDs, and bumper stickers bearing the freshly trademarked Snowball name. An official Facebook page is now mostly an outlet for fanciful “Snowball: The Dancing Parrot” cartoons; the latest one, when I checked, featured Snowball competing in dressage at the Olympics. YouTube has its own channel where you can watch Snowball gyrating to everything from Queen to Lady Gaga.

But Schulz never dreamed that her rescue bird celebrity might be scientifically important. Ani Patel, who promptly contacted Irena Schulz when he first saw Snowball’s video, also wasn’t sure at first. The neurobiologist was stunned by the bird’s apparent ability to dance to a beat, but wasn’t convinced that it hadn’t been trained, or that its owner wasn’t leading its movements off camera. Could Snowball the dancing cockatoo truly synchronize his movements to music?

Patel and Schulz conducted a little experiment to find out. Patel used a computer program to alter Snowball’s favorite Backstreet Boys song, “Everybody (Backstreet’s Back),” into eleven different versions, each on the same pitch but with different tempos, from 20 percent slower to 20 percent faster than the original. Then Schulz played each version to Snowball on camera while she stood quietly in a corner, watching the bird perform by himself. At slower speeds, Snowball sometimes swayed from side to side, slow jamming, while in the

speeded-up trials he spontaneously slammed his feet up and down in time to the tune. Mostly, he stuck to one basic move: a simple head bob.

Patel meticulously analyzed the videos of each trial, marking the exact frame when each of Snowball’s head bobs reached its lowest point. Then he compared those time points with corresponding beats in the music to find out whether they coincided.