The Third Reich at War (68 page)

Spotting a group of Soviet fighters above him, he pulled out of his dive and raced up towards them. ‘The love of the chase,’ he confessed, ‘and a sense of indifference had taken hold of my reactions.’ Flying in a steeply banked curve, he got behind one and shot it down. It was a foolhardy action. ‘As I turned round to look for the Russian fighters,’ he wrote in his diary after the incident, ‘I saw their blazing guns eighty yards behind me. There was a terrific explosion and I felt a hard blow on my foot. I twisted my Messerschmitt and forced it up into a steep climb. The Russian was shaken off.’ But Einsiedel’s plane was badly damaged, his guns had been put out of action, and he had to limp back to base.

237

Such incidents occurred on a daily basis over Stalingrad during the late summer and autumn of 1942 and inevitably took their toll. Senior officers disapproved of spectacular individual actions, which, they said, wasted fuel. From now on, Einsiedel’s unit was ordered to support the German infantry and to avoid engaging Soviet fighters. It was a losing battle. ‘Breakdowns reached enormous proportions . . . A fighter group of forty-two machines seldom had more than ten machines operational.’ The odds were impossible. On 30 August a shot penetrated Einsiedel’s engine cooler as he was flying low over the Russian lines, and he crash-landed. Miraculously, Einsiedel was unhurt. But Soviet troops quickly arrived on the scene. They stole all his personal belongings before taking him off to be interrogated.

238

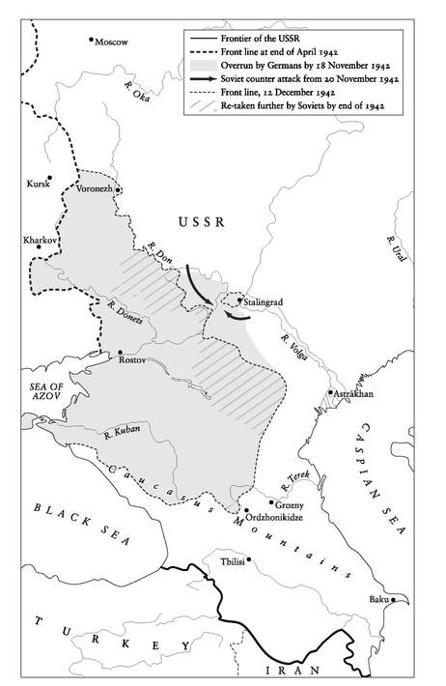

As Einsiedel had noted, the German planes had failed to establish complete air superiority in the area; as fast as they lost planes to the German air aces, the Soviets rushed replacements to the combat zone from other fronts. Yet, on the other hand, the Soviet air force had not achieved domination either. Throughout the spring and summer of 1942, while the German fliers continued to dispute the command of the skies with Soviet fighter-pilots, the German ground forces of Army Group B were advancing steadily on the city of Stalingrad, the gateway to the lower Volga river and the Caspian Sea. The Germans had so far failed to take either Moscow or Leningrad. For Hitler in particular, it was all the more important, therefore, that Stalingrad should be captured and destroyed. On 23 August 1942 wave after wave of German planes carpet-bombed the city, causing massive damage and loss of life. At the same time, German tanks advanced virtually unopposed, reaching the Volga to the north. As the bombing continued, now reinforced by German artillery, Stalin allowed civilians to begin evacuating the city, which was rapidly crumbling into uninhabitable ruins. On 12 September 1942 German troops from General Friedrich Paulus’s Sixth Army, backed by General Hermann Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army, entered Stalingrad. It only seemed a matter of weeks before the city fell. But the German

commander was in some ways less than ideally suited for the job of taking the city. Paulus had been deputy chief of the Army General Staff before being given his command early in the year. Born in 1890, he had spent almost his entire career, including the years of the First World War, in staff posts, and had almost no combat experience. In this situation, he depended heavily on Hitler, whose achievements as a commander filled him with awe. On 12 September, as his troops were entering the city, Paulus was conferring with the Leader at Vinnitsa. The capture of Stalingrad, the two men agreed, would give the German forces command of the entire line along the Don and Volga rivers. The Red Army had no more resources; it would collapse, leaving the Germans free to devote their efforts to speeding up the advance into the Caucasus. The city, Paulus assured the Leader, would be in German hands within a few weeks.

239

After that, Hitler had already decided, the entire adult male population of the city would be killed, and the women and children would be deported.

240

By 30 September 1942 Paulus’s men had overrun about two-thirds of the city, prompting Hitler to announce publicly that Stalingrad was about to fall. Hitler’s speech did a good deal to strengthen the troops’ faith in ultimate victory. ‘The Leader’s great speech,’ reported Albert Neuhaus from the Stalingrad front to his wife on 3 October 1942, ‘has only strengthened our belief in it by another 100%’.

241

But speeches would not overcome the Soviet resistance, whatever their effect on morale. Senior generals, including Paulus and his superior Weichs, and Halder’s successor Zeitzler, all advised Hitler to order a withdrawal, fearing the losses that would be incurred in a lengthy period of house-to-house fighting. But for Hitler the symbolic importance of Stalingrad now far outweighed any practical considerations. On 6 October 1942 he reaffirmed that the city had to be taken.

242

Similar considerations ruled on the other side. After a year of almost continuous defeat, Stalin had decided to throw as many of his resources as possible into the defence of what was left. The city bore his name, and it would be a major psychological blow if it fell. At the same time, feeling battered by the defeats of the previous months, he decided to give a free hand to the chief of the general staff, General Aleksandr Vasilevskii, and Georgi Zhukov, the general who had stopped the German forces at Moscow a year before, in organizing the overall campaign in the south. Stalin gave the command over Red Army forces in the city itself to General Vasili Chuikov, an energetic professional soldier in his early forties. Chuikov had had a chequered career, having been sent off to China in disgrace, as Soviet Military Attach’, following the defeat of his Ninth Army by the Finns in the Winter War in 1940. Stalingrad, where he was put in charge of the Sixty-Second Army, was his chance to prove himself. Chuikov understood that he had to ‘defend the city or die in the attempt’, as he told the regional political boss, Nikita Khrushchev. He stationed armed Soviet political police units at every river crossing to intercept deserters and execute them on the spot. Retreat was unthinkable.

243

German aircraft and artillery continued to attack the Soviet-occupied part of Stalingrad, but the bombed-out ruins of the city provided the Soviet troops with ideal conditions for defence. Digging in behind heaps of rubble, living in cellars and posting snipers in the upper floors of half-demolished apartment blocks, they were able to ambush the advancing German troops, break up their mass assaults, or channel the enemy advance into avenues where they could be disposed of by concealed anti-tank guns and heavy weaponry. They laid thousands of mines under cover of darkness, bombed German positions at night and set up booby-traps to kill German soldiers as they entered houses. Chuikov formed machine-gun squads and arranged for supplies of hand-grenades to be shipped into the city.

244

Often the fighting was hand-to-hand, using bayonets and daggers. The struggle rapidly became a battle of attrition. Constant, unremitting combat increasingly took its toll and many soldiers fell sick. Their letters home are full of bitter disappointment at being told they were having to spend a second consecutive Christmas in the field. Despite the danger of being discovered by the military censor, many were quite frank. ‘I’ve only got one big wish left,’ wrote another on 4 December 1942, ‘and that is: that this shit soon comes to an end . . . We’re all so depressed.’

245

Yet it was in the rear of Paulus’s forces, rather than in the city itself, that the Soviet breakthrough would come. Zhukov and Vasilevskii persuaded Stalin to bring in and train large quantities of fresh troops, fully equipped with tanks and artillery, to try to mount a huge encirclement operation. The Soviet Union was already producing over 2,000 tanks a month to Germany’s 500. By October the Red Army had created five new tank armies and fifteen tank corps for the operation. Over a million men were assembled ready for a massive assault on Paulus’s lines by early November 1942.

246

Zhukov and Vasilevskii saw their chance when Paulus’s superior, General Maximilian von Weichs, in command of Army Group B, decided to help Paulus concentrate his forces on taking the city itself. Romanian forces would take over about half the German positions to the west of Stalingrad, freeing up German forces for the assault on the city itself. He thought of them as more than a rearguard. But Zhukov knew that the Romanians had a poor military record, as did the Italians who were stationed alongside them in the north-west. He moved two armoured corps and four field armies to confront the Romanians and Italians to the north-west of Hoth’s armoured forces, and another two tank corps to face the Romanians in the south-east, on the other side of the German armour. Strict secrecy was maintained, radio traffic reduced to a minimum, troops and armour moved up at night and camouflaged during the day. Paulus failed to strengthen his defences, preferring to keep his tanks close to the city, where they were of little use. On 19 November 1942, their preparations finally complete, and with favourable weather conditions, the new Soviet forces attacked at a weak point in the Romanian lines almost 100 miles west of the city. 3,500 guns and heavy mortars opened fire in the early morning mist, blasting a way through for the tanks and infantry. The Romanian armies were unprepared, lacking in anti-tank weapons, and were overwhelmed. After putting up an initial fight, they began to flee in panic and confusion. Paulus reacted too slowly, and when he eventually sent tanks to try to shore up the Romanian lines, it was too late. They were no match for the massed columns of T-34 tanks now pouring through the gap.

247

Soon the rapid Soviet advance was pushing back the German lines as well, driving back Paulus’s men towards the city. None of the German generals had reckoned with a Soviet attack in such strength, and it was some time before they realized that what was in progress was a classic encirclement manoeuvre. So they failed to move troops up to prevent the Soviet tank thrusts from meeting up with one another. On 23 November 1942 the two tank columns met up at Kalach, completely cutting off Paulus and his forces from the rear and leaving Hoth’s armour marooned outside the encircled area. With twenty divisions, six of them motorized, and nearly a quarter of a million men in total, Paulus’s first thought was to try to break out to the west. But he had no clear plan, and once more he hesitated. The idea of a breakout would have meant a retreat, abandoning the much-trumpeted attempt to capture Stalingrad, and Hitler was unwilling to sanction a withdrawal because he had already announced in public that Stalingrad would be taken.

248

Speer reported him at the Berghof in November 1942 complaining privately that the generals consistently overestimated the strength of the Russians, who he thought were using up their last reserves and would soon be overcome.

249

Acting on this belief, Hitler organized a relief force under Field Marshal von Manstein and General Hoth. Manstein’s belief that he could succeed in breaking the encirclement strengthened Hitler in his refusal to allow Paulus to withdraw. On 28 November 1942 Manstein sent a telegram to the beleaguered forces: ‘Hold on - I’m going to hack you out of there - Manstein.’ ‘That made an impression on us!’ exclaimed one German lieutenant in the Stalingrad pocket. ‘That’s worth more than a trainload of ammunition and a Ju[nkers] full of food supplies!’

250

III

Manstein’s forces, two infantry divisions, together with three panzer divisions, all under Hoth’s command, advanced on the Red Army from the south on 12 December 1942. To counter this, Zhukov attacked the Italian Eighth Army in the north-west, overrunning it and driving south to cut off Manstein’s forces from the rear. By 19 December 1942 the German relief armour had been stopped in its tracks, 35 miles away from Paulus’s rear lines. Nine days later it was virtually surrounded, and Manstein was forced to allow Hoth to retreat. The relief operation had failed. There was nothing left for Paulus but to attempt a breakout, as Manstein told Hitler on 23 December. But this still looked like abandoning the entire attempt to take the city, and so, once again, Hitler refused. But Paulus told him that the Sixth Army had only enough fuel for its armour and transport to go for 12 miles before it ran out. G̈ring had promised to airlift 300 tons of supplies into the pocket every day to keep Paulus’s men going, but in practice he had managed little more than 90, and even Hitler’s personal intervention failed to boost it to anything more than 120, and that only for about three weeks. Planes found it difficult to land and take off in the heavy snow, and airfields were under constant attack from the Russians.

251

Supplies were getting low, and the situation of the German troops in the city was becoming increasingly desperate. By now, they were doing little except trying to stay alive. Most of them were living in cellars or underground bunkers or in foxholes in the open, which they tried to line and cover with brick and wood as best they could. Often they furnished and decorated them to try to re-create a homely atmosphere. As one soldier reported to his wife on 20 December 1942:

We’re squatting here with 15 men in a bunker, i.e. in a hole in the ground roughly the size of the kitchen in Widdershausen [his home in Germany], everyone with his clobber. You can well picture for yourself the terrible overcrowding. Now the following picture. One man is washing himself (insofar as water is available), a second is delousing himself, a third is eating, a fourth is cooking a fry-up, another is asleep, etc. That’s roughly the milieu here.

252