The Time of Our Lives (20 page)

Read The Time of Our Lives Online

Authors: Tom Brokaw

No other city in America has access to as much private wealth as greater New York, but this is about more than the money. It’s about the idea and the selfless execution. Robin Hood could be a template for other cities on a smaller scale.

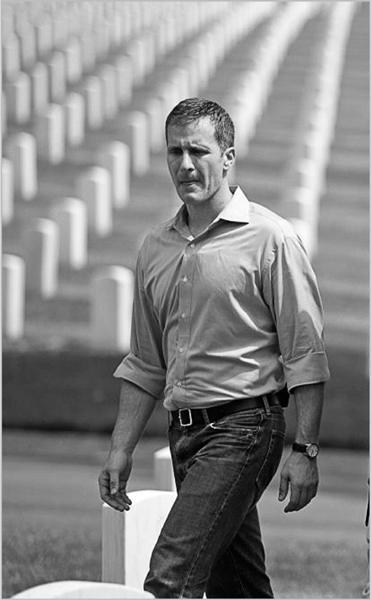

So could the mission of a former Rhodes scholar turned Navy SEAL.

Eric Greitens isn’t waiting for a public service academy to turn out a new generation of public servants. He’s establishing his own corps from the growing ranks of wounded veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. He calls it “The Mission Continues,” a phrase that came to mind during a visit to the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda.

Lieutenant Greitens, a Navy SEAL who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, was recovering from his own combat wounds, which were not extensive, when he went to check on some of his more seriously injured comrades. Making conversation, he asked what they wanted to do when they recovered. To a man, they said they wanted to return to their units. One young man summed up the spirit of the ward: “I lost my legs,” he said. “That’s all. I did not lose my desire to serve or my pride in being an American.”

The powerful idea of continuing service even after paying such a high price led Greitens and his friend Kenneth Harbaugh to form The Mission Continues, a 501(c)(3) that places wounded vets in fourteen-week fellowship programs with charitable organizations such as the Boys and Girls Clubs of America. They get cost-of-living expenses and a renewed sense of worth. The organizations get a well-trained and highly motivated volunteer.

When I met Eric at a VA hospital in St. Louis I thought, Here’s a modest young man with nothing to be modest about. He was an honors student at Duke University before earning a PhD in political science at Oxford University as a Rhodes scholar. His doctoral thesis was called “Children First,” a study he conducted to determine the most effective ways humanitarian organizations can help children affected by war.

Eric’s work in places such as Rwanda, the Gaza Strip, Croatia, and Albania resulted in an award-winning collection of his photographs in the report

Save the Children: Community Strategies for Healing

, a publication of the Save the Children Foundation, Zimbabwe University, and Duke University.

Eric Greitens, founder of The Mission Continues

(Photo Credit 11.2)

After Oxford, he could have opted for the cushy, tweedy life of a college professor but instead he volunteered for the Navy SEALS, the elite warriors who earn their place by undergoing a six-week training program that pushes the candidates to the very edge of physical, psychological, and emotional surrender.

Following his combat tours in Afghanistan and Iraq, Eric returned home to earn one of the highly competitive slots as a White House fellow, the prestigious program that boasts Colin Powell, Kansas governor Sam Brownback, former labor secretary Elaine Chao, and retired CNN chief executive Tom Johnson among its graduates.

As he moved back into civilian life, Eric never forgot the first and last rule of military leadership. As he told me in our first meeting, “You take care of your guys and just because we came off the battlefield, that doesn’t mean we’re gonna stop taking care of them.”

We were in a rehabilitation ward for severe spinal cord injuries, watching Jamey Bollinger, an Army veteran who was caught in an IED detonation in Iraq, patiently go through his therapy routine, his lifeless legs and arms hooked up to electronic stimulators and motors so he could exercise in hopes of regaining some muscle tone. Jamey, from a small town just across the state line in Illinois, was dressed in a St. Louis Cardinals jersey and baseball cap and much more eager to talk about the Redbirds’ pennant chances than his injuries.

“Jamey’s a perfect example,” Eric said. “We have so many wounded and disabled veterans coming back in their twenties and we want to be sure we’re there for them fifty, sixty, seventy years from now. Their whole community needs to be around them, not just for the first six months but for the rest of their lives.”

The best way to do that, Eric believes, is to find a role for the wounded vets in their communities, to give them an opportunity to serve so they’re not just dependent on someone else. In the long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, an estimated thirty thousand Americans have been wounded in combat or seriously injured in war-zone accidents.

In many cases, the wounds are so severe the injured would not have lived just twenty years ago, but thanks to greatly enhanced on-site treatment, speedy evacuation, and especially the advanced surgical and medical procedures once the wounded reach a base hospital, the survival rate is by far the best of any war in which the United States has been involved.

That’s unconditionally good news, but it also means those with severely debilitating conditions—paralysis, blindness, brain injuries—will require special assistance the rest of their lives. “The Pentagon and Veterans’ Administration have to find better models for reintroducing the vets into society,” Eric said. “The VA still is a hospital model—for treatment and release. Local communities, many of them small towns in the rural areas, have to take ownership of their native sons and daughters returning with lifelong wounds and limited futures. We’ve got to figure out a way to help those communities. The government can pay but that’s just a start.”

THE PROMISE

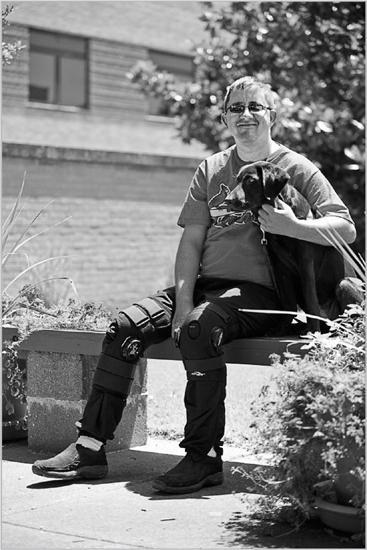

By mid-2010 he had sixty-six full-time fellows, and more than four hundred vets had gone through the program. One of them, Phillip Sturgeon, a fourteen-year Army veteran, suffered head injuries and had developed post-traumatic stress disorder when I met him at the VA hospital in St. Louis. He was training a Labrador pup to be a service dog for the physically challenged. He called the dog L.T., short for “Lieutenant.”

Before Sturgeon heard about The Mission Continues, he had about given up, and it was a strain on his family. “I thought my service and I thought my life was pretty much at an end,” Sturgeon told me as we sat on a gurney in the hospital’s spinal cord rehabilitation ward while Jamey Bollinger continued his workout at the other end, assisted by a team of cheerful, athletic young women specially trained for this kind of therapy.

Sturgeon, a large, quiet man—shy, really, except when he lights up about L.T.—went on, “L.T. gives me purpose. He helps me deal with anxiety every day and he gives me purpose because I know by training him I’m giving back to the community. When I finish with his training he can help someone in a wheelchair.”

Sturgeon hopes The Mission Continues will also help educate the civilian population about the debilitating effects of PTSD. “I don’t think a lot of people understand how it affects the guys who come home, their families, how they live through the nightmares and sleepless nights. Not knowing how to adjust to everyday life after being in a situation like that [Iraq] every day.”

As L.T. pulled on his leash and Sturgeon’s wife and a daughter listened in, smiling, Sturgeon said, nodding to the puppy, “That gives me something to look forward to and it was a huge relief because it brought my whole family back together.”

Phillip Sturgeon, wounded in Iraq and now a part of The Mission Continues

(Photo Credit 11.3)

Phillip Sturgeon’s whole family includes his father, a Vietnam veteran, confined to a wheelchair because of wounds he suffered in that war. When Sturgeon finished his training, L.T. became the service dog for his father.

As I was writing this in Montana after a beautiful, sunny day of fly-fishing and horseback riding with my family, Greitens sent an update on Sturgeon that rocked me emotionally. He wrote that as a result of his traumatic brain injury, “Phil is losing his vision and will soon be blind. Since his original plan to train service dogs is no longer possible we’ve found a place for him with the Red Cross.”

My God, I thought, how much does one family have to go through? How many Phil Sturgeons are out there, in small towns, second- or third-generation military vets so disabled?

We must ensure they are not consigned to a life of constant difficulties, surrounded by the indifference of their fellow citizens.

CHAPTER 12

Wire the World but Don’t

Short-Circuit Your Soul

FACT:

More than a billion people a day sign on to the Internet for commerce, communication, or research on everything from junior high term papers to complex and sophisticated medical, academic, economic, and political issues; they’re looking for a mate or a used book, a new weapons system or an ant farm. There has never been such a transformative technology so instantly and easily available.

QUESTION:

When was the last time you had a conversation in school, at work, or in a bar about the real meaning of all this communication capacity? Or, as a Stanford law student said to me, “When are we going to have a serious discussion about the new meaning of ‘friend’?”

F

or some reason I am still invited to deliver college commencement speeches, a flattering but demanding exercise because I use the occasions to take the measure of what I think I’ve learned in the past four years and what may be useful to graduates one-third my age.

In the week preceding my 2006 commencement address at Stanford, the student newspaper interviewed graduating seniors, asking what they thought of me as a choice to launch them on their way. One young woman said, “Tom Brokaw? That’s like listening to adult radio.”

So when I took the podium I singled her out by name and said, “Turn your iPod to adult radio if you’d like, but I have something to say to your classmates that may have more relevance.”

It got a big laugh, and her parents caught up to me later to say, in effect, “She had it coming.”

What I tried to do that day for those students in the heart of Silicon Valley, at the womb of so many cyberspace geniuses, is to remind them of a wider obligation that goes well beyond logging on.