The Time of Our Lives (28 page)

Read The Time of Our Lives Online

Authors: Tom Brokaw

CHAPTER 17

The Grandparent Lode

FACT:

According to a study by Grandparents.com, by 2015, 59 percent of grandparents will be baby boomers, and they’re already changing the model of grandparenthood.

As history’s most prosperous generation they’re inclined to indulge their grandchildren, spending $52 billion a year on goods and services for grandkids. They have also established a new naming pattern for their role.

Contemporary grandchildren no longer see Grandma as the Betty Crocker type in the kitchen. Harvard, MIT, and Brown have grandmother-eligible women as presidents. We’re on our third female secretary of state. There are now three women on the U.S. Supreme Court.

The most influential European leader during the economic downturn was Angela Merkel, chancellor of Germany. Brazil has elected its first woman as president, Dilma Rousseff.

In my family, we are dominated by the female sex. I have three daughters and four granddaughters. Male dominance, once taken for granted, is now in play and I fully expect that the twenty-first century will be the first in which women approach full parity.

QUESTION:

How do contemporary grandparents fit into this new reality and keep pace with the evolution of opportunity and expectation? Should there be a new model of grandparenting?

THE PAST

A

s I think back on my parents and grandparents, somehow they were always more mature than their ages and always active citizens. Or perhaps it was just expected of them, a condition of their time in the Great Depression and World War II. They went from their teenage wardrobes to suits and ties, sensible shoes, and grown-up dresses. Those who didn’t conform were likely to be thought of as not entirely trustworthy, inspiring comments such as “Oh, you know, Bill just doesn’t want to grow up.”

Until John F. Kennedy came along, men in their twenties wore hats better suited to men in their forties. Jackie Kennedy, just thirty-one when her husband was elected, was a welcome change for young women who had come of age with their mothers looking more like Mamie Eisenhower than any of the Kennedy women.

It went well beyond wardrobes. The Organization Man was expected to get in line and wait his turn. Women were expected to marry early, have babies early, and go gray in their late forties. Early marriage was part of the compact of a purposeful life.

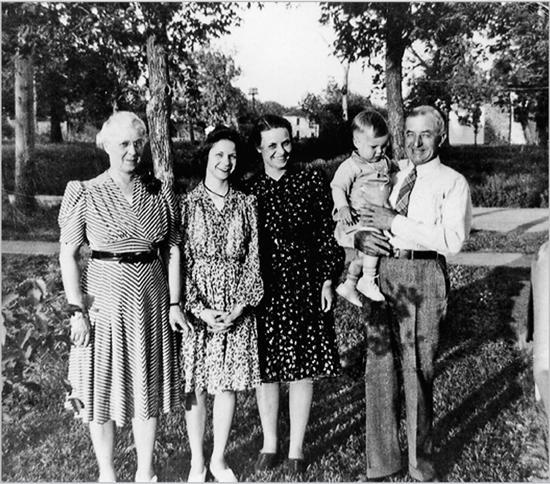

Me with grandparents Ethel and Jim Conley, Aunt Marcia, and my mother, Jean Brokaw, in 1941

(Photo Credit 17.1)

THE PRESENT

Fast-forward to the generational conceit of my age group: We think we’ll be forever young, with the latest running shoes, faded denims, leather jackets, and more toys than our kids.

We can spend now and catch up later, for as Fats Domino sang, “Let the Good Times Roll.”

Together Meredith and I intellectually understood that when our daughters married they’d have children and we’d become grandparents, but I don’t think we saw ourselves as “Grandma and Grandpa,” an old, white-haired couple in tweeds wearing only sensible shoes.

When we became grandparents we were determined, I think, to carry that attitude forward, to give that role fresh meaning, however surprised we may have been by the fact of grandparenthood itself. We felt we were still young and on the come line of life, and that would connect us to our grandchildren in a new manner.

First, there was the naming thing. What would be we called? Meredith immediately said she wanted to be called Nan, the endearing name of her beloved maternal grandmother. I didn’t have a family reference. My grandparents were, in fact, Grandma and Grandpa.

I remember the reaction of Robert Redford when he became a grandfather to two energetic munchkins. We were walking out of a restaurant after a day of skiing. Bob was every inch the Sundance Kid, lean and athletic in boots, blue jeans, and a buckskin jacket. Bystanders gave him the long, admiring stares reserved only for the biggest stars.

Suddenly his red-haired toddler grandkids came running after him, calling out, “Grandpa Bob, Grandpa Bob!” Bob turned and scooped them up, laughing, realizing he’d been busted. Loud enough for his fans to hear, he said, “Not in public, kids. Not in public.”

Informally I surveyed friends and others who were also entering this new, welcome, and yet unaccustomed place in life. A dashing airline pilot I met at a Jackson Hole cocktail party said with a self-aggrandizing air, “I’ve told my grandson to call me Sport.”

I preferred the mischievous response of my friend Peter Osnos, the book publisher. “I have them call me Elvis,” he said. “What do they know?”

A longtime friend in South Dakota, Larry Piersol, a federal judge, was plainly pleased when his grandchild spotted him wearing a large hat at the family farm and immediately began calling him Cowboy. A New York neighbor, a distinguished psychiatrist, is a Belgian native, so he came up with Le Grand Papa.

Another new grandfather about my age had recently married a younger woman and insisted that his grandson call him by his first name, Ben. And so he did, and the two of them became very close. When Ben visited his grandson’s preschool on grandparents’ day the child looked up and said, “Ben! What are you doing here?” Ben replied, “It’s grandparents’ day. I’m your grandfather.” The child’s eyes widened and he said, “You

are

?”

THE PROMISE

Some of what I’ve already discovered is that my generation has to race to keep up with the world of our grandchildren. By the time they’re six or seven, they’re into the dazzling world of information technology, sitting at computer terminals with their own log-ins and favorite sites, playing video games that are much more engaging than the Dick and Jane books of our youth.

The small screen, I’ve discovered, can be a mutually rewarding meeting place for grandparents and their grandchildren. Email, Skype, and Facebook are happy new forms of communication across generational lines. The latest arresting image on YouTube or a virtual tour of a location in the news may not completely replace “Over the river and through the woods to grandmother’s house we go,” but they can be an agreeable conduit between generations widely separated by age. That electronic connection is still very much a work in progress, but it has infinite possibilities.

This new generation is also growing up on a palette in which the colors are much more vivid than they were for most of us my age. Their world reflects the steady rise in ethnic integration, from classrooms to after-school activities, television shows and commercials, movies and public life. Well before Barack Obama became the first African American president, there were black, Latino, and Asian school administrators, mayors, and members of Congress and city councils.

When NBC broadcast a retrospective of my journalism career it included coverage of the civil rights movement out of Atlanta in the sixties. Our San Francisco granddaughters, Claire and Meredith, at the time eight and six years old, were stunned and upset by the images of black people being sprayed with fire hoses and beaten as they marched for their rights. “What was that all about?” they demanded to know of their mother. It was entirely alien to their experience.

They had a similar reaction when in the winter of 2010 I did a lengthy report during the Vancouver Olympics on Gander, Newfoundland, which became a safe port in the storm of uncertainty during the 9/11 attacks. Thirty-seven transatlantic flights and their seven thousand passengers headed to the United States were ordered to land at Gander as part of the airspace shutdown.

The generous and matter-of-fact manner in which the Gander community took in all those strangers on such short notice—fed them, comforted them, and provided beds and even clothing, all at no cost—was so inspiring I suggested to my son-in-law Allen and daughter Jennifer that they watch with Claire and Meredith, by then thirteen and eleven years old.

It didn’t occur to me or to their parents that the 9/11 attacks, which are so vivid for us, occurred when they were just four and two. As a result they had no clear memory of that awful time and so they rushed to Google to learn more.

For my part, I realized that America has been at war in Afghanistan and Iraq during most of their lives, but because they have no family members or friends involved, that, too, is not part of their active consciousness. The tedious security procedures at airports are for them routine; they’ve never known any other way to board a plane.

Like every generation, their time is being defined by new realities, many of them unforeseen but with certain advantages. When each of our grandchildren was born I had the same thought: Welcome. You’re off to a good start. You’ve been born in America into loving, stable families with strong traditions of parenting.

I was never more proud of our middle daughter, Andrea, an executive at Warner Music, than when she was frazzled one Sunday morning while dealing with thirty-month-old Vivian and twelve-month-old Charlotte, trying to give each newly awakened toddler breakfast and attention.

I said, “Motherhood is a lot more demanding than you expected, right?” Andrea paused in the middle of putting a fresh diaper on Charlotte, laughed, and said, “Yeah, Dad, but it is so much

fun.

” She wasn’t kidding, this free-spirited Berkeley graduate who spent her twenties and most of her thirties hanging out at rock clubs and concerts, trying to find the next Bruce Springsteen.

Jennifer, our eldest daughter and a physician, shares the joy of parenting with her sister as she shepherds her two daughters through preteen and teenage commitments to school, chorus, soccer, field trips to local attractions, and summer trips to Italy and London.

Jennifer has started a new business as a consulting physician after twelve hard years working in San Francisco and Albuquerque emergency rooms, but she’s determined not to dial back her attention to Claire and Meredith or her husband, Allen, a prominent and very busy radiologist.

She recognizes the pressures for women of her generation who want to do it all, including, in her case, a demanding training regimen for long-distance swimming in San Francisco Bay.

“Dad,” she’ll say, “it wears me out but I know it’s worthwhile.”

Sarah, our youngest, is not married at age forty-one and with every passing year the idea of becoming a single mother plays a larger role in her life. Frozen embryos, a surrogate, and adoption are subjects a new generation of grandparents have come to know in a way our parents could not have imagined. A clinical therapist, Sarah transformed her personal and professional experience with these issues and others affecting modern young women into a popular book called

Fortytude: Making the Next Decades the Best Years of Your Life—Through the 40s, 50s, and Beyond

.

Exploring the myriad questions facing women in their forties is another manifestation of the social and cultural evolution of Sarah’s generation. Confronting these changes as a grandparent is a handy way of calibrating the course of our life histories. When I participated in a grandparents’ day at Claire and Meredith’s school in the fall of 2009, a teacher asked the grandparents and her students to record side-by-side accounts of life in the seventh grade for the two generations. All the grandparents except one who had attended a public school in the Bronx remarked on the de facto and legal separations of the races in their seventh-grade experiences. We also commented on the inequality of opportunities between boys and girls, especially in athletics.

The grandchildren seemed amused and slightly bewildered by what I am sure they considered to be ancient history. Their lists made no reference to race or gender. They began with computers and video games. They also call their teachers by their first names—remember, this was in San Francisco—a practice that in my time would have meant a note to the principal’s office about the troublemaker in the back row.