The Time of Our Lives (31 page)

Read The Time of Our Lives Online

Authors: Tom Brokaw

Meredith’s paternal grandfather, a no-nonsense but lovable country physician, was known to everyone as simply “Doc.” He taught her to drive on isolated rural roads when she could barely see over the steering wheel and played daily word games when she visited him and her grandmother Bird during the summer.

Doc was an amateur geneticist and such a wise observer of the political world that George McGovern, South Dakota’s liberal senator, always made it a point to stop for a visit when he was in the vicinity, even though Doc was a card-carrying Republican.

Doc’s been gone for more than half of Meredith’s life and yet she remembers his many influences on her as if they were passed along yesterday. Her maternal grandparents, Gramp and Nan, were equally important to her formative years, in part because they shared Doc and Bird’s values, if not their politics. Gramp was a populist Democrat when he met Franklin Delano Roosevelt as a vice presidential candidate in the twenties.

They got along well, and FDR appointed Gramp to New Deal–era commissions during the Depression and World War II. When Meredith’s father was gone for five long years during the war, she lived with Gramp and Nan in their home next to the Masonic lodge where he was executive secretary, a position that paid little but perfectly positioned him as a wise counselor to what passed for the community’s power structure.

Guy and Edyth Harvey, Meredith’s maternal grandparents

(Photo Credit 18.2)

It was in their home that Meredith developed a lifelong interest in politics and the news of the day. Meredith, Gramp, and Nan would gather around the large cabinet radio in the living room with Nan’s doilies draped over the sofa and Gramp’s White Owl cigar burning in the standing ashtray.

Like Doc, his good friend and a favorite political debating opponent, Gramp was revered for his tireless enthusiasm for good works and pride in all things South Dakota. Thanks to his FDR connection, he was a ranking official in the March of Dimes campaign, the crusade to find a cure for polio.

Gramp was literally larger than life, at six feet five and close to three hundred pounds, always with a black Stetson and, until late in his life, a lit cigar in his hand. He liked a shot of whiskey and a beer chaser, the cowboy cocktail known as a “bump and a beer.” His childhood was shaped by the calloused-hands way of life of West River country, the rolling grassland and badlands west of the Missouri River.

Nan, a quiet, diminutive woman, was raised in the same area on a remote, economically marginal ranch. During the deathly flu epidemic of 1918, she rode on horseback from ranch to ranch, doing what she could to help families who were losing members to the lethal strain of influenza.

She would recall with a small smile how she and her sister would help with haying in the summertime. Often when they would buck up a load of fresh-cut hay the air would fill with rattlesnakes that had been caught in the harvest.

Gramp had an extensive vocabulary in Lakota, the language of the state’s Sioux tribes, and taught Meredith to count in the Indian way. As a ten-year-old he met Calamity Jane on a Sunday morning in a Fort Pierre bar. He was on his way to Sunday school when he found an empty whiskey bottle, which could be redeemed for a nickel.

“There was this rough-looking woman at the bar on Sunday morning,” he liked to recall, and “she made fun of my tie, grabbing it and cutting it off with a big knife. I began to cry and she felt bad so she handed me a silver dollar. That’s when I found out it was Calamity Jane.”

My favorite Gramp story, however, involved the death of his hero, President Roosevelt, in 1945. Think of the timing. The end of World War II is in sight. The promise of prosperity is bright after fifteen years of economic depression and the trauma of war. Suddenly, the great man who led the nation through all of that is gone.

For Gramp, it was also a deeply felt personal loss. “I locked myself in my room for two days,” he said, “smoked cigars, drank whiskey, and cried. Finally, I came out”—and here his voice would drop an octave as he said, “and Edith [Nan] understood.”

Those stories and the influences of Doc and Bird, Gramp and Nan, have stayed with Meredith for more than sixty years.

There were no trust funds or European junkets, no new cars at graduation or fancy watches. Both sets of grandparents would take the grandkids for a week to a rustic cabin on a Minnesota lake in the summer or on a train ride across Canada. Maybe they’d slip a five-dollar bill in a card on a teenager’s birthday, but that would be the limit of material gifts.

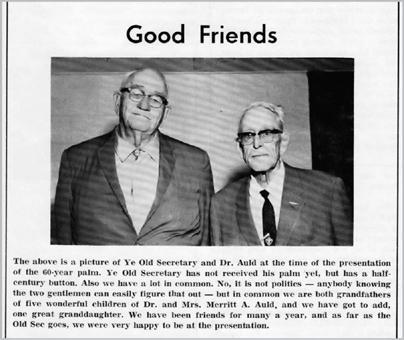

Meredith’s grandfathers, Guy Harvey and Clarence “Doc” Auld: One was a Democrat, the other a Republican, but politics never affected their deep friendship.

(Photo Credit 18.3)

In remembering them and my grandparents, Meredith and I both have the same recollections: They were always engaged citizens, attentive to local and national politics and international affairs. When I was too young to fully comprehend what he was trying to teach me, my grandfather would open

Time

magazine to trace the maps of World War II. He also suggested to my mother that she keep the encyclopedia in the bathroom so we could read while in the tub or on the john. She resisted, but somehow we all turned out okay anyway.

I like to think that if Doc, Gramp, and my grandpa were still with us they’d be asking, “Have you thought about learning to read and speak in the Chinese language? Or Arabic?”

Meredith remembered her grandfathers getting together and promising not to argue about politics but failing. “Doc and Gramp always had heated but respectful discussions about politics when they got together and they weren’t parroting someone else. They did their homework, and anyone listening would be enlightened. It was just part of my growing up.”

THE PROMISE

We were blessed to be surrounded by elders who were always active, involved citizens in small ways and large.

What better legacy for one generation to pass along to another? Meredith and I have tried to keep that perspective in mind. If we can have the same influence on our grandchildren as our grandparents had on us, that will be reward enough.

We learned early as grandparents that close-to-the-ground, very personal excursions can lead to some essential truths. A few years ago, Meredith and I took our San Francisco granddaughters on an overnight camping trip to a backcountry cabin in the Montana mountains. It was not an easy hike, leading through trackless timber and up steep slopes, but despite some small-bore protesting about the bugs and the isolation, the girls made it.

After a cookout we explained to Claire and Meredith, then nine and seven, that they would be sleeping inside the darkened cabin, which had been a cowboy’s one-room shelter during roundup time. Meredith assured them, “Tom and I will be right outside.”

We slipped into our sleeping bags under the stars and listened to the girls’ whispers from inside the tiny cabin. Suddenly, the youngest of the two appeared and said in a commanding voice, “Nan, we need an adult in

here

—NOW.”

Don’t we all?

S

ometimes those reminders of adult roles and responsibilities come in unexpected fashion. In June 2006, I was in Montana on a bluff overlooking a grove of conifers alongside the west Boulder River, which was close to flood stage because of the heavy snowpack runoff.

As I stood there a small herd of elk cows—mothers—emerged from the tree line with their new calves. They paused to look at me and apparently decided that I was far enough away to do no harm, and so they stepped into the raging river to lead their children to the grassy pastures on the other side.

It was not an easy crossing. The calves struggled against the current and then had to thrash their way through thick brush on the far bank. One calf failed and was swept downstream, swimming frantically until he reached an eddy and was able to gain a sandbar on the side from which he’d started.

He waded into the river and failed again, repeating the retreat to the eddy and the sandbar. He tried a third time and still didn’t make it. When he got back to the sandbar he was trembling, and I wondered, What now?

On the far bank, the rest of the herd waited patiently as the mother of the frightened calf stood at the water’s edge and, as God is my witness, nodded her majestic head to him, as if to say, “It’s okay; I’m coming to get you.”

With that she waded into the river and crossed over to him, nuzzling him for a moment before leading him upstream to an easier passage. They rejoined the rest of the herd and trotted off to greener pastures.

I was so moved by the experience I could barely breathe, and once again I was reminded that every year the creatures of the wild teach me something about life as it should be lived.

I shared the story with our grandchildren and friends over the years, extending the metaphor about maternal care to include the obligation we all have to one another when we reach our own flood-stage rivers. We navigate them successfully when we do it together.

For Claire and Meredith

,

Vivian and Charlotte

,

and grandchildren everywhere

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book first began to take shape in my mind as I traveled across America on U.S. Highway 50 for a study of the American character commissioned by Bonnie Hammer, the enterprising and creative head of USA, the cable channel that is such an important part of the NBC family. Martha Spanninger led our Peacock Productions team on the long road from the eastern shore of Maryland to Sacramento, California, with stops in Washington, D.C.; Ohio; Indiana; St. Louis, Missouri; Kansas; Colorado; and Nevada. In every location I visited with fellow citizens who shared their wisdom, concerns, and determination not to lose the American Dream. I am eternally grateful for their cooperation and insights.