The Time of Our Lives (30 page)

Read The Time of Our Lives Online

Authors: Tom Brokaw

But bullying is, alas, an exception to the growing place of racial tolerance, and it is in that arena that grandparents can and should be proactive mentors within their families and in schools as volunteers. My generation can bear witness to the shameful treatment of people of color and the hope that almost all of us had that we could move beyond it.

That we have made great progress is testimony first to the courage and vision of the people of the movement, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., but also to the determination of the rest of the population to march beyond the stain of institutionalized and de facto racism. It should be a matter of generational pride, just as the acknowledgment and diminution of bullying can be a matter of pride for our grandchildren.

To do that we have to find the cyber fusion between our grandchildren and our use of this technology. Websites could be established for interactive conversations and re-publication of the most disturbing images from the civil rights struggle. Online word games could be lessons in hurtful, even hateful, language. It could be an exercise that would help heal the wounds within our generation while providing a forum for intergenerational understanding.

The discussions need not be confined to bigotry or social cruelty. What about a dialogue on the public use of language? When did the F-word become acceptable outside the locker room or barroom? Tell me about your purple hair. Is it only me or do others wonder what the grandparents of the randy, exhibitionist cast of

Jersey Shore

think when they watch Snooki and Paulie and their antics? For that matter, how would you like Paris Hilton as a granddaughter or Charlie Sheen as a grandson? Curious minds want to know.

Attention to personal health and extended longevity are also benchmarks for our generation worth celebrating for the benefit of our grandchildren. At a reunion of high school friends recently—all of us seventy years old or older—I asked, “Who in our town was seventy when we were in high school?” I stumped the gathering. Finally one of the old gang remembered a banker who may have lived his three score and ten. Men, especially, were dying in our town in their late fifties and early sixties with distressing regularity.

In their case, lifestyle was a major factor. They grew up in a world of cigarettes and cigars, marbled beef, mashed potatoes and gravy, fried chicken and butter on everything (even on a slice of cake for my dad), all-you-can-eat buffets, and whipped cream lathered on whatever was for dessert. God forbid they would be caught jogging or biking. Walking from the golf cart to the bar at the end of a motorized round of eighteen holes was about the extent of their regular exercise.

My father and both of Meredith’s parents died before they were seventy. My mother lives on into her nineties, thanks, in part, I believe, to a move to California where her lifestyle took on a healthier mien.

Meredith and I have been physically fit since our twenties when we both gave up smoking and began a regular exercise regimen, so our grandchildren have no reason to focus on our diet. I suspect, however, that they may be aware of our appetite for “things.” As a result, and for our own ease of mind as well as setting the right kind of grandparent example, we’re shrinking, not expanding, our material world.

Our generation has not been a model of temperate materialism, even as we embraced and initiated what has come to be known as the environmental movement. “Reduce, reuse, and recycle” should become our mantra when organizing the next stage of our lives, as an example to the generations that follow.

The psychic and physical energy required to manage too many toys can drain the pleasure of having them.

There is a form of schizophrenia that comes with having grown up with the sensibilities of Great Depression–era parents and the acquisitive traits of my generation. I sometimes open a cabinet filled with seldom-used dishes or sweaters or whatever and feel a wave of guilt, thinking, “We must eat dinner off those plates tonight and I’ll wear two of the sweaters!”

“Need” should overwhelm “want” in these years, and our needs should grow smaller and smaller as we advance in age. For too many baby boomers, however, need has taken on a new meaning in the Great Recession, which came along at exactly the wrong time in their lives. As a group, boomers have been on a long joyride of “spend for today and worry about tomorrow two days from tomorrow.” It was not only the largest generation in American history but also the wealthiest and most determined to spend, spend, spend.

When the economy took a steep dive, so did the assumptions of baby boomers, now grandparents. Their home values plummeted, their retirement accounts dried up or were greatly reduced, and their expectations for the future took a dark turn. Even financially secure boomers were unsettled by the speed and the reach of the downturn.

It has been, at best, a sobering experience and I do not mean to diminish its effects, but it can also be an instructive lesson to future generations. With our help, grandchildren can learn from our experience. At their age, net worth has little real meaning. It is our love and life they want to share—but we can impart the lessons of managing for the future and not just for instant gratification.

For those of us who were lucky enough to catch the wave of financial security, we can give up a lot and continue to live at a standard unimaginable when we were starting out. It is a matter of reordering priorities.

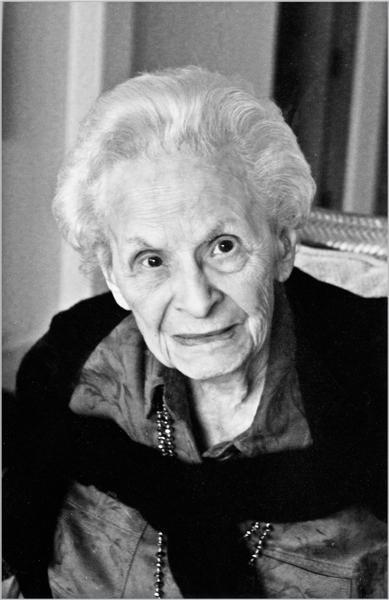

For me, I was helped, as always, by my mother, Grandma Jean, a child of the early twentieth century, a survivor of hard times, and a living exemplar of everyday wisdom.

When she was ninety-three years old Mother spent a few days in Montana at a family reunion at our remote ranch. It wasn’t an easy trip. She has limited mobility because of arthritis in her spine, so we borrowed a wheelchair and made some modifications in her bedroom of our hundred-year-old farmhouse.

It’s a small house by modern standards, just two bedrooms—one up and one down—but a wraparound addition on the river side added a dining room, fireplace, and sitting area. The kitchen is functional but not a candidate for a Martha Stewart taping.

Altogether I doubt the original house plus the addition add up to

1,100

square feet, including the porch and what we in the West call the mudroom, a back entry where muddy boots and wet jackets are shed.

Mother appeared every morning at the kitchen table, dressed in a light robe, complaining mildly about the cool Montana dawns and sometimes asking, “Where am I?” To help her through her confusion I would quickly ask questions about her childhood on the South Dakota farm where she started life.

THE PAST

She’d pause over her scrambled eggs, look to the distance, and say, “My father made me eat oatmeal every morning in front of the big black kitchen stove where my mother made toast. I hated the oatmeal—still do—but we made wonderful ice cream.”

And she’d be off, recalling horse-and-buggy trips to town to buy blocks of ice and the hurried trips back to the farm to store the ice in an insulated icebox that had no electrical refrigeration.

“It was a lot of work,” she’d say. “We’d have to chip away at the ice with a pick and hand-crank the real cream and sugar we used, but it was so good.” Her expression would become puzzled and she’d say aloud, to no one in particular, “What were the names of our horses? I used to remember them all. I think Gladys was the horse that drank from the stock tank and then leaked all the water out of her mouth all the way back up the hill.”

Her gaze would drift to our modest kitchen and she’d say, “Our house then was about the size of this room and maybe one other,” then she’d return to her breakfast, shaking her head slightly.

I’d sit and watch, occasionally prompting her with questions but mostly trying to see in my mind’s eye a slide show of her life.

With my father, she got through the Depression and World War II by getting up every morning with the same set of values as the day before: family first, hard work, faith, thrift, moderation, and community.

Mother, particularly, was interested in politics, an admirer first of FDR and then Harry Truman, who physically resembled her father. Mother and Dad were registered Democrats but skeptical about John F. Kennedy’s stylish ways; Hubert Humphrey was more their kind of guy, a native of South Dakota who took Main Street with him wherever he went.

The fifties were boom years for my parents and other working-class folks. They bought their first home and first new car. My father was making respectable wages as a hard-hat-wearing, lunch-box-carrying foreman for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on the big flood control and hydroelectric dams being constructed on the Missouri River.

They were saving money for my college education and spending Saturday nights having dinner, drinking a few highballs, and dancing with friends at the local Elks Club. Life was good.

Like so many members of their generation, they were unprepared for the upheaval of the sixties. They were opposed to the war in Vietnam but even more opposed to the idea of college deferments from the draft. When my brother shipped out as a marine, headed for Vietnam (he made it back), my father called me to rail against college boys getting a pass.

I initially made a feeble defense but quickly conceded he was right. We had equally spirited arguments about hair length and militant movements.

The night Mike left for the war, Mother and Dad were on a road trip back to South Dakota from visiting us in Atlanta. They stopped in Tennessee and, anxious about their youngest son’s safety, they uncharacteristically hit the hotel bar for a couple of belts.

Mother had her first taste of Jack Daniel’s, Tennessee’s homegrown sour mash whiskey.

Years later she would remember that stressful night and say, “But I was helped by that good whiskey—what do they call it? Tennessee walking horse whiskey?” The Brokaw boys would tease her about her drinking naïveté. She never did become a Jack and Coke kind of mom.

When my father retired in the early eighties he and Mother moved into a two-bedroom condominium surrounded by the lush vegetation of Southern California in a large Orange County retirement community. They’d return to South Dakota for the summer months, but it was clear California was becoming a large part of their lives.

Dad would spend his weekdays as if still on the job, in the community woodworking shop, making traditional baby cradles for younger friends who were giving him a growing brood of surrogate grandchildren to go with his own. Winter evenings he’d often step out onto his balcony overlooking the flowering trees and sun-washed bougainvillea bushes, laugh, and say aloud, “If the boys in Bristol could see me now,” a reference to his hardscrabble hometown on the northern prairie of South Dakota.

In 1983, his journey from a childhood of deprivation and despair to working-class prosperity, respectability, and real, measureable accomplishment came to an abrupt end. He died of a massive coronary at the age of sixty-nine the week before I was to begin anchoring the

NBC Nightly News

.

Mother wisely concluded, “South Dakota doesn’t need another widow.” She moved permanently to California and for the next thirty years she had a life she never could have imagined as a young woman.

She returned to Europe for a second time, cruised through the Panama Canal, and found a male friend in her bridge club. Together they sailed the Alaska coastline. She went to concerts in Los Angeles and became an enthusiastic fan of the Angels of the American League and the Lakers of the NBA.

When I got her an autographed picture from Kobe Bryant she was thrilled, until he got in trouble in Colorado. Then she took down the picture but did not throw it away. When the Lakers began to win championships again, she put Kobe back on the wall and never conceded that she might have been guilty of a sliding scale of worthiness.

When age and infirmities began to overrun her enthusiasm for an active life she retreated to her assisted living apartment without rancor or complaint. She would occasionally say, matter-of-factly, “I’ve lived long enough” or “I never expected to live this long.” Yet she would soldier on, and made a difficult trip to Montana for a gathering of her boys and our families.

She’d sit in her wheelchair at lunch in our rustic lodge, gazing out at the river running through the property, the thick, golden grass on the hillsides, the stately cottonwoods, Douglas firs, and aspen trees framing the distant mountains, and ask, “Now where are we?” When I answered, “We’re on our ranch, Mom. Remember, Meredith and I bought this twenty years ago. You’ve been here before.”

She’d shake her head slightly, pat me on the hand, and then, noticing I was wearing my fishing cap indoors, she’d silently gesture with her arthritic hands for me to take it off.

In her nineties, Grandma Jean remains the family role model.

(Photo Credit 18.1)

No caps at lunch in her presence, ever.

When she returned to California, Meredith and I reflected on the lessons of our grandparents and how they have stayed with us.