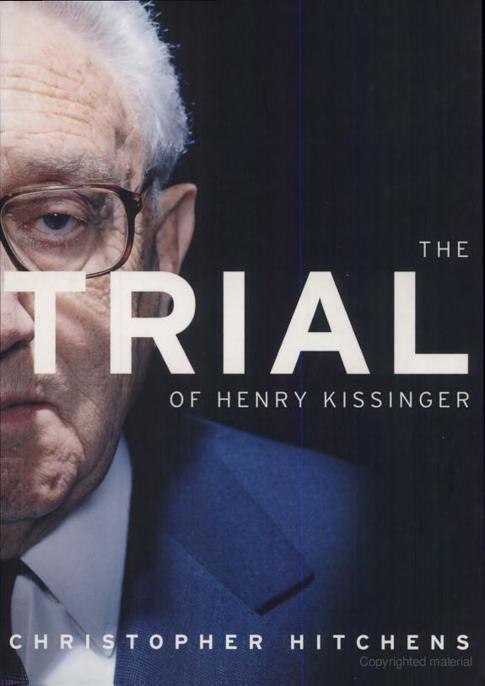

The Trial of Henry Kissinger

Read The Trial of Henry Kissinger Online

Authors: Christopher Hitchens

Tags: #Political, #Political Science, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Statesmen, #United States, #History, #Political Crimes and Offenses, #Literary, #20th Century, #Government, #International Relations, #Political Freedom & Security, #Historical, #Biography, #Presidents & Heads of State

The Trial Of Henry Kissinger

ALSO BY CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS

Prepared for the Worst: Selected Essays and Minority Reports The Elgin Marbles: Should they be returned to Greece? Hostage to History: Cyprus from the Ottomans to Kissinger

Blaming the Victims (edited with Edward Said) James Callaghan: The Road to Number Ten (with Peter Kellner)

Karl Marx and the Paris Commune

The Monarchy: A Critique of Britain's Favourite Fetish Blood, Class and Nostalgia: Anglo-American Ironies

For the Sake of Argument: Essays and Minority Reports

International Territory: The United Nations 1945-95 (photographs by Adam Bartos) The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice When the Borders Bleed: The Struggle of the Kurds (photographs by Ed Kashi) No One Left to Lie To: The Values of the Worst Family Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere

THE TRIAL OF HENRY KISSINGER

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS

VERSO

London • New York

First published by Verso 2001

© Christopher Hitchens 2001

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

- Publisher:

Verso (June 17, 2002) - Language:

English - ISBN-10:

1859843980 - ISBN-13:

9781859843987

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F OEG USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014-4606

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books www.versobooks.com ISBN 1-85984-631-9

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset by M Rules Printed by R. R. Donnelley & Sons, USA

For the brave victims of Henry Kissinger,

whose example will easily outlive him, and his "reputation."

And for Joseph Heller, who saw it early and saw it whole.

In Gold's conservative opinion, Kissinger would not be recalled in history as a

Bismarck, Metternich or Castlereagh but as an odious schlump who made war

gladly.

{Good as Gold, 1976)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

CURTAIN-RAISER: THE SECRET OF '68

INDOCHINA

A SAMPLE OF CASES: KISSINGER'S WAR CRIMES IN INDOCHINA BANGLADESH: ONE GENOCIDE, ONE COUP AND ONE ASSASSINATION

CHILE

AN AFTERWORD ON CHILE

CYPRUS

EAST TIMOR

A "WET JOB" IN WASHINGTON

AFTERWORD: THE PROFIT MARGIN

LAW AND JUSTICE

APPENDIX I: A FRAGRANT FRAGMENT

APPENDIX II: THE DEMETRACOPOULOS LETTER

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INDEX

PREFACE

IT WILL BECOME

clear, and may as well be stated at the outset, that this book is written by a political opponent of Henry Kissinger. Nonetheless, I have found myself continually amazed at how much hostile and discreditable material I have felt compelled to omit. I am concerned only with those Kissingerian offenses that might or should form the basis of a legal prosecution: for war crimes, for crimes against humanity, and for offenses against common or customary or international law, including conspiracy to commit murder, kidnap and torture.

Thus, in my capacity as a political opponent I might have mentioned Kissinger's recruitment and betrayal of the Iraqi Kurds, who were falsely encouraged by him to take up arms against Saddam Hussein in 1974-75, and who were then abandoned to extermination on their hillsides when Saddam Hussein made a diplomatic deal with the Shah of Iran, and who were deliberately lied to as well as abandoned. The conclusions of the report by Congressman Otis Pike still make shocking reading, and reveal on Kissinger's part a callous indifference to human life and human rights. But they fall into the category of depraved realpolitik, and do not seem to have violated any known law.

In the same way, Kissinger's orchestration of political and military and diplomatic cover for apartheid in South Africa and the South African destabilization of Angola, with its appalling consequences, presents us with a morally repulsive record. Again, though, one is looking at a sordid period of Cold War and imperial history, and an exercise of irresponsible power, rather than an episode of organized crime. Additionally, one must take into account the institutional nature of this policy, which might in outline have been followed under any administration, national security advisor, or secretary of state.

Similar reservations can be held about Kissinger's chairmanship of the Presidential Commission on Central America in the early 1980s, which was staffed by Oliver North and which whitewashed death squad activity in the isthmus. Or about the political protection provided by Kissinger, while in office, for the Pahlavi dynasty in Iran and its machinery of torture and repression. The list, it is sobering to say, could be protracted very much further.

But it will not do to blame the whole exorbitant cruelty and cynicism of decades on one man.

(Occasionally one gets an intriguing glimpse, as when Kissinger urges President Ford not to receive the inconvenient Alexander Solzhenitsyn, while all the time he poses as Communism's most daring and principled foe.)

No, I have confined myself to the identifiable crimes that can and should be placed on a proper bill of indictment, whether the actions taken were in line with general "policy" or not.

These include:

1.

The deliberate mass killing of civilian populations in Indochina.

2.

Deliberate collusion in mass murder, and later in assassination, in

Bangladesh.

3.

The personal suborning and planning of murder, of a senior constitutional

officer in a democratic nation - Chile - with which the United States was

not at war.

4.

Personal involvement in a plan to murder the head of state in the

democratic nation of Cyprus.

5.

The incitement and enabling of genocide in East Timor.

6.

Personal involvement in a plan to kidnap and murder a journalist living in

Washington, DC.

The above allegations are not exhaustive. And some of them can only be constructed prima facie, since Mr. Kissinger - in what may also amount to a deliberate and premeditated obstruction of justice - has caused large tranches of evidence to be withheld or destroyed.

However, we now enter upon the age when the defense of "sovereign immunity" for state crimes has been held to be void. As I demonstrate below, Kissinger has understood this decisive change even if many of his critics have not. The Pinochet verdict in London, the splendid activism of the Spanish magistracy, and the verdicts of the International Tribunal at The Hague have destroyed the shield that immunized crimes committed under the justification of raison d'etat. There is now no reason why a warrant for the trial of Kissinger may not be issued, in any one of a number of jurisdictions, and why he may not be compelled to answer it. Indeed, and as I write, there are a number of jurisdictions where the law is at long last beginning to catch up with the evidence. And we have before us in any case the Nuremberg precedent, by which the United States solemnly undertook to be bound.

A failure to proceed will constitute a double or triple offense to justice. First, it will violate the essential and now uncontested principle that not even the most powerful are above the law. Second, it will suggest that prosecutions for war crimes and crimes against humanity are reserved for losers, or for minor despots in relatively negligible countries. This in turn will lead to the paltry politicization of what could have been a noble process, and to the justifiable suspicion of double standards.

Many if not most of Kissinger's partners in crime are now in jail, or are awaiting trial, or have been otherwise punished or discredited. His own lonely impunity is rank; it smells to heaven. If it is allowed to persist then we shall shamefully vindicate the ancient philosopher Anacharsis, who maintained that laws were like cobwebs: strong enough to detain only the weak, and too weak to hold the strong. In the name of innumerable victims known and unknown, it is time for justice to take a hand.

INTRODUCTION

ON 2 DECEMBER 1998

, Mr. Michael Korda was being interviewed on camera in his office at Simon and Schuster. As one of the reigning magnates of New York publishing, he had edited and "produced" the work of authors as various as Tennessee Williams, Richard Nixon, Joan Crawford and Jo Bonanno. On this particular day, he was talking about the life and thoughts of Cher, whose portrait adorned the wall behind him. And then the telephone rang and there was a message to call "Dr" Henry Kissinger as soon as possible. A polymath like Mr.

Korda knows - what with the exigencies of publishing in these vertiginous days - how to switch in an instant between Cher and high statecraft. The camera kept running, and recorded the following scene for a tape which I possess.

Asking his secretary to get the number (759 7919 - the digits of Kissinger Associates) Mr.

Korda quips drily, to general laughter in the office, that it "should be 1-800-cambodia ... 1-800-bomb-cambodia." After a pause of nicely calibrated duration (no senior editor likes to be put on hold while he's receiving company, especially media company), it's "Henry - Hi, how are you?... You're getting all the publicity you could want in the New York Times, but not the kind you want ... I also think it's very, very dubious for the administration to simply say yes, they'll release these papers ... no ... no, absolutely ... no ... no ... well, hmmm, yeah. We did it until quite recently, frankly, and he did prevail ... Well, I don't think there's any question about that, as uncomfortable as it may be. ... Henry, this is totally outrageous ... yeah ... Also the jurisdiction. This is a Spanish judge appealing to an English court about a Chilean head of state. So it's, it ... Also Spain has no rational jurisdiction over events in Chile anyway so that makes absolutely no sense ... Well, that's probably true ... If you would. I think that would be by far and away the best ... Right, yeah, no I think it's exactly what you should do and I think it should be long and I think it should end with your father's letter. I think it's a very important document ... Yes, but I think the letter is wonderful, and central to the entire book. Can you let me read the Lebanon chapter over the weekend?" At this point the conversation ends, with some jocular observations by Mr. Korda about his upcoming colonoscopy: "a totally repulsive procedure."

By means of the same tiny internal camera, or its forensic equivalent, one could deduce not a little about the world of Henry Kissinger from this microcosmic exchange. The first and most important thing is this. Sitting in his office at Kissinger Associates, with its tentacles of business and consultancy stretching from Belgrade to Beijing, and cushioned by innumerable other directorships and boards, he still shudders when he hears of the arrest of a dictator.

Syncopated the conversation with Mr. Korda may be, but it's clear that the keyword is

"jurisdiction." What had the New York Times been reporting that fine morning? On that 2

December 1998, its front page carried the following report from Tim Weiner, the paper's national security correspondent in Washington. Under the headline "U.S. Will Release Files on Crimes Under Pinochet," he wrote:

Treading into a political and diplomatic confrontation it tried to avoid, the United States decided today to declassify some secret documents on the killings and torture committed during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in Chile...The decision to release such documents is the first sign that the United States will cooperate in the case against General Pinochet. Clinton Administration officials said they believed the benefits of openness in human rights cases outweighed the risks to national security in this case.

But the decision could open "a can of worms," in the words of a former Central Intelligence Agency official stationed in Chile, exposing the depth of the knowledge that the United States had about crimes charged against the Pinochet Government...

While some European government officials have supported bringing the former dictator to court, United States officials have stayed largely silent, reflecting skepticism about the Spanish court's power, doubts about international tribunals aimed at former foreign rulers,

and worries over the

implications for American leaders who might someday also be accused in

foreign countries,

[italics added]