The Triumph of Seeds (17 page)

Read The Triumph of Seeds Online

Authors: Thor Hanson

Tags: #Nature, #Plants, #General, #Gardening, #Reference, #Natural Resources

F

IGURE

7.1. A brine shrimp (

Artemia salina

), one of the few animals whose life cycle includes desiccation and dormancy similar to that found in seeds. Photo © by Hans Hillewaert/CC-BY-SA-3.0. W

IKIMEDIA

C

OMMONS

.

The biology of dormancy has implications for everything from pharmaceuticals to space exploration. NASA scientists study seeds to develop new storage and survival strategies for long missions. When astronauts bolted a case of basil seed to the outside of the International Space Station, the dormant little pips did just fine, germinating normally after more than a year of exposure. At the seed bank, however, most research has a more earthbound goal: keeping people fed in a rapidly changing world. Seed banks act as giant

libraries of variation that farmers and plant breeders can turn to when certain crop traits are needed. After the 2004 tsunami flooded coastal rice paddies from Indonesia to Sri Lanka, seed banks quickly provided salt-tolerant varieties to replant the fields. And when the Russian wheat aphid threatened America’s grain crops in the 1980s, researchers screened more than 30,000 seed-bank varieties to find the strains with natural resistance. With commercial agriculture increasingly focused on a few, mass-produced crops, seed banks provide an important hedge against disease outbreaks, natural disasters, and the steady loss of food-plant diversity around the world. In the years ahead, they’re also expected to play a vital role in our adjustment to another global trend.

I visited Fort Collins in the middle of May, but it could have been August. The thermometer hovered around 90°F (32°C), setting a string of daily records 20 degrees above the average. Two weeks earlier, another weather record had been set—for snowfall. In that context, my conversation with Chris Walters naturally turned to climate change. “It’s already affecting how we collect and what we collect,” she told me. I asked for an example, and she replied in a flash: “Sorghum. It’s going to be huge.” She explained how this tall, African grass was naturally adapted to a warm climate. “It’s the hot, dry grain, and we’ll all be growing more and more of it.” Planning for that future, the seed bank’s collection already contains 40,000 different sorghum samples.

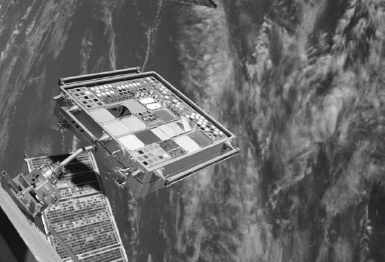

F

IGURE

7.2. This experiment on the International Space Station exposed 3 million basil seeds to the cold vacuum of space for more than a year. Later dispersed to scientists and school groups, the seeds sprouted successfully. P

HOTO

NASA MISSE 3,

COURTESY OF

NASA.

If Chris is right, then seed banks will play a key role in the era of climate change, easing our transition to alternative, warm-weather crops. But they also protect agriculture against catastrophic events—wars, natural disasters, or political upheavals that can bring whole farming systems to a halt. In 2008, scientists unveiled a new international seed repository in the Norwegian Arctic. Carved deep into a mountainside in the Svalbard archipelago, it preserves seeds in cold, dry darkness with little need for additional refrigeration or other support from above. “If there are any big problems on the outside,” its founding director noted,

“this is going to survive.” Dubbed the “Doomsday Vault,” its opening made headlines around the world.

F

IGURE

7.3. Sorghum (

Sorghum bicolor

). A hot-country grain native to Ethiopia, sorghum is expected to become increasingly important as the world adjusts to climate change. The kernels can be ground into flour, fermented to make beer, and even puffed as an alternative to popcorn. I

LLUSTRATION

© 2014

BY

S

UZANNE

O

LIVE

.

“Fear sells,” Chris quipped when I mentioned the Svalbard project. But she quickly added that everyone in the seed community was grateful for the publicity. The attention raised the profile of their work and provided a needed boost in the constant struggle for funding. And running a seed bank is anything but cheap. While words like “vault” and “bank” imply simply turning the key and walking away, managing a seed collection requires constant activity. Even in cold storage, the samples steadily degrade and must be checked continuously to make sure they’re still viable. “The original plan was every seven years, but we don’t have the budget for that,” Chris told me when we toured the germination lab. We stopped by a bench where a technician showed us trays of bean seedlings, each sprout carefully wrapped in damp paper towel. “So now we’re on a ten-year cycle . . . but we don’t have the budget for that either!”

Without regular germination tests, the seeds in any given sample could wink out before anyone noticed. “They die from an accumulation of insults,” Chris explained. Small problems add up over time, like the aches and pains that everyone starts to feel as they age. Taken separately, none of these is serious, but when seeds pass a certain threshold their viability suddenly drops off to nothing. The trick lies in catching a sample before that happens, so that the seeds can be planted, grown to maturity, and then harvested to restock the collection. Regenerating older samples can keep a seed collection viable in perpetuity, but with varieties ranging from tropical cashews to winter-hardy kales, no single facility can handle all that planting.

“We don’t do that part here,” Chris said, sounding relieved. Instead, she and her team partner with over twenty regional seed banks and research stations in locations (and climates) as diverse

as North Dakota, Texas, California, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico. They also collaborate with the seed vault at Svalbard and with an impressive facility for wild species

managed by Kew Gardens. In fact, the number of seed banks worldwide is growing rapidly as governments, universities, and private groups recognize the threats posed by declining crop diversity and the loss of native plants. “There are over a thousand of us now,” Chris announced toward the end of our day together. “It’s becoming a movement!” Like any movement, seed banking has its villains and heroes. The villains tend to be faceless—large-scale patterns of habitat loss or trends in global agriculture. But in one case the role of “seed enemy” was played by a very recognizable historical figure: Joseph Stalin. Because when Stalin turned against the scientific community and began jailing Soviet scholars and intellectuals, his victims included the movement’s first and most enduring hero, a brilliant botanist whose work influenced crop breeding for generations and paved the way for every seed bank that followed.

Though he is little known outside botanical circles, many regard Nikolai Vavilov as one of the greatest scientists of the twentieth century. The son of a wealthy industrialist, he survived the Bolshevik Revolution by virtue of his expertise. V. I. Lenin may have deplored the educated “intelligentsia,” but he also believed in a science-based approach to modernizing Soviet agriculture. During the crippling grain shortages of 1920, Lenin diverted scarce funds from relief efforts to found the Institute of Applied Botany. “The famine to prevent is the next one,” he famously told a colleague,

“and the time to begin is now.”

As the institute’s first director, Vavilov received generous support for his plant breeding research and, by extension, his passion for seeds. He traveled widely and gathered samples by the ton, gaining a deep appreciation for how crops such as wheat, barley, corn, and beans varied from place to place—maturing early or late, surviving frosts, or

resisting pests and disease. Better than anyone else in his generation, Vavilov understood how these traits could

be stored indefinitely, in the form of seeds, and used to breed new varieties. He dreamed of developing crops specifically tailored to Russia’s harsh climate, varieties that would end his country’s persistent and deadly food crises. Within a few years, he transformed a tsarist palace in downtown Leningrad into the world’s largest seed bank and research facility, supported by a staff of hundreds working in field stations across the country.

Unfortunately, Stalin did not share his predecessor’s enthusiasm for scientific crop breeding, and he showed little patience for Vavilov’s time-consuming methods. Soon after Lenin’s death, the seed-bank program—and the Mendelian genetics on which it was based—fell out of favor. When another famine struck the country in 1932, Stalin threw his support behind the “barefoot scientists”—a cadre of untrained proletariat agriculturalists who

promised quicker results. Vavilov found his research increasingly thwarted, and he was eventually arrested on trumped-up charges of sabotaging Soviet agriculture. He continued to write about seeds and crop plants in prison until his strength finally failed him. Neglected by his jailors, this champion of feeding the hungry suffered a final irony: he died of starvation.

But while Vavilov languished in prison, his ideas took on a life of their own. Soon seed banks based on the Russian model began springing up around the world. The United States broke ground in Fort Collins at the height of the Cold War, after the

Sputnik

launch inspired a widespread effort to “catch up” with Soviet science. Nazi Germany pursued a more direct route. During the siege of Leningrad, Hitler dispatched a special commando unit with instructions to secure Vavilov’s seed bank at all costs and bring the collection home to Berlin. The city never fell, but the seed bank still faced a constant threat of looting by the starving populace. At least four devoted workers died from hunger without ever touching the thousands of packets of rice, corn, wheat, and other

precious grains in their care.

Surprising stories of seed heroism continue to the present day. As US troops advanced on Baghdad in 2003, Iraqi botanists frantically

packed samples of their most important seeds and shipped them to a facility in Aleppo, Syria. Everything that stayed behind was destroyed. Ten years later, the Syrians did the same thing, evacuating their entire collection mere days before Aleppo became a battleground in their own burgeoning war. Unfortunately, no amount of courage can save some collections. Somalia lost its two seed banks during the 1990s; Sandinista rebels looted Nicaragua’s national collection; and invaluable strains of wheat, barley, and sorghum disappeared from Ethiopia’s seed bank during the 1974 war that toppled Haile Selassie.

In light of this history, the high security and Cadillac-proof walls at Fort Collins start to make more sense. But while few people would argue that seeds aren’t worth protecting, I hadn’t heard Chris Walters or anyone else mention a fundamental irony underlying the whole seed-bank movement. Until very recently, crop diversity pretty much took care of itself, maintained by the same farmers, gardeners, and plant tinkerers that developed it in the first place. Wherever people farmed, they bred local varieties and kept them “banked” in their fields, replanting and refining them season after season. Saving that diversity only became an issue after the advent of industrial agriculture, with its focus on high yields from a few varieties

grown on a massive scale. As impressive and necessary as seed banks have become, they are in many ways an elaborate fix to a problem of our own making.

“I agree completely,” Chris said when I posed this dilemma. “The best kind of conservation is in situ.” For crops, that means in a farmer’s field; for wild species, it means in a healthy expanse of natural habitat. “But that’s not always possible,” she went on simply, showing the pragmatism that makes her such a good scientist. “Seed banking is something we

can

do, and so we should. It’s a way of buying time.”

Because of dormancy, boosted by refrigeration, seed banks can indeed buy a great deal of time. But while they will always be a vital resource for plant research and breeding, there is still the question

of what they’re buying time for—what changes in human activity would lead to the kind of in situ conservation that Chris was talking about? Part of the answer lies not in a laboratory or a cryogenic tank, but on a small farm outside the town of Decorah, Iowa, population 8,121. There, for nearly forty years, a group of dedicated gardeners have kept thousands of different vegetable varieties growing, not just in their own fields, but in garden plots around the world.