The Triumph of Seeds (19 page)

Read The Triumph of Seeds Online

Authors: Thor Hanson

Tags: #Nature, #Plants, #General, #Gardening, #Reference, #Natural Resources

F

IGURE

8.1. The busy squirrels from

The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin

(1903), Beatrix Potter’s classic story about gathering (and dispersing) the acorns and hazelnuts of Owl Island.

An

almendro

seed measures two inches (five centimeters) long and slightly more than an inch (two and one-half centimeters) wide, with smooth sides and tapered ends that give it the appearance of a giant throat lozenge. Like the pit of a peach or plum, this seed includes an extra layer of stony shell, with the soft

nut tucked safely inside. The surrounding flesh of the fruit is thin and brownish-green, but sweet enough to attract a wide array of monkeys, birds, and bats. At the height of the season, dozens of species gather around

almendros

, foraging in the canopy and feasting on the bounty that drops to the ground below. But among all these fruit-eaters, only one large bat carries its meal away from the tree. So if an

almendro

wants its young dispersed, it must also concentrate on the creatures that eat its seeds. And while it may be hard to think of trees as intelligent (at least outside of J. R. R. Tolkien stories), the system

almendros

have developed seems careful, calculating, and nearly perfect.

From a plant’s perspective, not all potential dispersers are created equal. When I collected

almendro

seeds, for example, I carted off large quantities and traveled great distances, but then systematically destroyed every one of them for my research. Even if I’d planned on sprouting the seeds, my laboratory was at a university in northern Idaho, hardly the right habitat for rainforest trees. At the other end of the spectrum, smaller rodents, like rice rats and pocket mice, lack the strength to move

almendro

seeds more than a foot or two. Invite them to the feast and the tree’s progeny would die without ever leaving home. Excluding small, ineffective seed predators and limiting the damage from large ones requires a shell with just the right level of defenses, one that optimizes what ecologists call

handling time

.

For

almendro

, the ideal shell turns out to be a woody husk that measures over a quarter of an inch (seven millimeters) thick at its widest point, twice the heft of a plum pit or a peach stone. The walls include additional protections: a layer of resinous crystals, much like the ground glass that exterminators add to concrete when they want to plug a rat hole. But in this case the seed isn’t trying to prevent gnawing entirely, just slow it down. For the average squirrel, chewing through the crystal-filled husk of an

almendro

takes at least eight minutes, and sometimes as much as half an hour. That’s a huge time investment for an animal that needs to locate and eat between 10 and 25 percent of its bodyweight every day just to survive. An

almendro

seed is worth the effort, but just barely. Spiny rats and smaller rodents rarely bother—not necessarily because they can’t, but because it’s not worth their while. The challenge and time involved would exhaust them to a degree that not even the reward of a large nut could repay. In this context, the strength and thickness of

almendro

shells seem perfectly adapted to reserving those nuts for squirrels, agoutis, and pacas—the large rodents most capable of carrying them away. Making them actually do so, however, lies beyond the control of the tree. That incentive must come from other players in the dance.

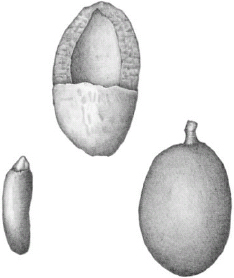

F

IGURE

8.2.

Almendro

(

Dipteryx panamensis

). Seeds of the mighty

almendro

tree lie within one of the toughest shells in nature, a defense against the gnawing teeth of rodents. The shell is pictured at the top, partially cut away in cross section. An extracted seed is shown on the left, with a whole fruit on the right. I

LLUSTRATION

© 2014

BY

S

UZANNE

O

LIVE

.

Once I perfected my mallet-and-chisel technique, I learned to cleave an

almendro

seed and neatly extract the nutmeat in less than a minute. That put me well ahead of squirrels, but it wouldn’t have seemed nearly fast enough if I’d been opening seeds in a dangerous setting—a crocodile pit, for example, or a pen full of hungry wolves. That’s the dilemma faced by rodents. Because as surely as an

almendro

tree attracts seed-eaters, it attracts the

eaters

of seed-eaters. I knew from experience that fer-de-lance hang around

almendro

trees, and so do other rodent-loving snakes like bushmasters and boa constrictors. I once watched a Semiplumbeous Hawk carry off something small and furred in broad daylight. If I’d stuck around until dark, I might have seen half a dozen different owls, as well as ocelots, margays, and jaguarundis, all of them attracted by the concentration of tasty prey. A friend of mine studying mammal communities once showed me a stack of photographs taken by remote cameras scattered throughout the forest—flash snapshots of surprised-looking jaguars, pumas, big weasels, and others. There were even a few hunters and their dogs. He asked me if anything seemed familiar, and then I saw it: time and again the backdrop included an

almendro

trunk, and the ground was littered with seeds. In the rainforests of Central America, the community of animals drawn to a good

almendro

crop doesn’t stop with fruit-eaters, seed-eaters, and predators. It includes all of the people who seek them: scientists, hunters, birdwatchers, and anyone else looking for a piece of the action.

In the face of all this commotion, much of it fanged and hungry, squirrels and other rodents usually treat

almendro

trees like a

drive-through. They pick up a meal and carry it away before stopping to eat—forty feet (twelve meters), fifty feet (fifteen meters), and sometimes much farther. Agoutis, in particular, turn out to be vital dispersers. They not only move seeds a long way, they bury them for safekeeping in tidy little holes throughout their home range, a habit with the pleasing name of

scatter-hoarding

. From the tree’s perspective, this fits the bill nicely: a creature that moves seeds and plants them, and then stands a good chance of being killed off by one of the many predators lurking nearby.

This pattern repeats itself with different rodent and plant species all around the world, providing ample evolutionary incentive for nut-like seeds to develop their thick, hard shells. In fact, any trait that adds to handling time can be an advantage, which is probably why walnuts have that brainy, convoluted shape that’s so irritatingly difficult to remove in one piece. Rodents, too, have responded with more than just strong teeth, developing bulging, high-capacity cheek pouches to carry off numerous seeds at once, as well as an uncanny ability to sniff out and discard diseased or worm-infested nuts before bothering to gnaw them. Like so many evolutionary stories, the impact of rodents on seed defense is more than a bilateral arms race. It involves a whole suite of relationships and species, with give-and-take on all sides. For the

almendro

, my research showed not only how elaborate that system can be, but how quickly it can fall apart.

In a healthy rainforest, crossing the muddy ground near large

almendro

trees feels like walking on lumpy gravel—gnawed, split, and otherwise discarded shells carpet the ground underfoot. I counted them by the thousands and rarely found an intact seed, let alone a young tree. With such a concentration of gnawers around, the only seeds that sprouted and grew into saplings were those that got themselves dispersed far away. In patchy forest, however, hunting and other disturbances took a heavy toll on large rodents, and there was hardly any sign of gnawing or scatter-hoarding. Seeds simply germinated where they fell, leaving every adult tree ringed by a thicket of its own children. In the short term, this scenario meant bad news

for the next generation—baby trees don’t fare well in the

shade of their parents. From an evolutionary standpoint, it put

almendro

in a bind—removing its partners in the dance left it with a seed too hard for anyone left in the forest to chew.

Studying

almendro

taught me that plants defend their seeds with a complex calculus where protection is only one of the variables. But it also left an obvious question unanswered: Just how hard is an

almendro

shell? Harder than concrete? I found the answer while writing this chapter.

Though I finished my dissertation years ago, a person doesn’t invest that kind of time in a project without taking home a few souvenirs. Dried now to a rough honey-brown, the

almendro

shell I keep on my desk still bears the telltale grooves of rodent bites at one end. To test it against concrete, I simply stepped outside of my office and crawled under the porch. The Raccoon Shack rests on a foundation of concrete pier blocks, the standard variety with a built-in bracket available at any home supply store. I placed my

almendro

shell edgewise against a pier block—like a chisel—and gave the thing a good solid whack with a hammer. It didn’t surprise me in the least to see cracks form in the concrete: if rodents evolved to gnaw, and

almendro

responded with one of nature’s hardest seeds, then

almendro

shells should be very nearly as tough as rat teeth. A few more whacks produced a sizable concrete chip that flew loose and landed in the soil below. I reached down to pick it up, careful to avoid the less savory items lying around under the porch: droppings and tattered feathers from our chickens, and half a dozen empty rat traps. One look at those traps annoyed me, and I made a mental note to return that evening and re-bait them with nut butter.

“People won’t believe you,” Eliza warned, smiling when I told her what was happening under the Raccoon Shack. But as Oscar Wilde once observed, “life imitates art far more than art imitates life.” And the fact remains that while I was sitting at my desk, writing about rodent teeth and seeds, a version of that same drama was playing out directly beneath my feet. Attracted by the grain in our

nearby chicken coop, an extended family of Norway rats had moved into the crawlspace under the Raccoon Shack. They gained entry by chewing a neat hole through a sheet of 23-gauge galvanized steel hardware cloth. Once inside, the rats had a cozy home base from which to stage raids on any nearby edibles. They soon discovered my pea bed, where I’d stupidly left the entire harvest for my Mendel experiment drying on the vine. By the time I figured out what was going on, the rats had decimated my Bill Jump Soup Peas and put a sizable dent in the Württembergische Wintererbse. The sad remnants that Noah and I picked through totaled a scant three cups, but luckily they included enough successful crosses to continue the experiment for another (better-protected) season.

L

osing my peas to the rats turned out to be a valuable lesson—as Mr. Wilde also noted, “experience is the name we give our mistakes.” First of all, I gained another insight into the methods of that cagey old monk. Unless the Monastery of St. Thomas maintained an army of cats, Mendel must have built a safe place to dry his harvest. It wouldn’t surprise me if his lost journals and papers contained detailed plans for a rat-proof granary. More importantly, I learned that even in the artificial setting of my pea bed, with a domestic vegetable and a nonnative rodent, the same rules apply. When the rats sniffed out my vines, they did their job perfectly, using the precise logic found in any rodent/seed interaction. Bill Jump peas mature slowly and hadn’t fully dried yet, making them comparatively easy to chew. Those were eaten on the spot. When I tried biting into a winter pea, however, I nearly broke a molar. They required more handling time, and, according to theory, should have been hauled away for safe gnawing. Sure enough, when I opened up the crawlspace under the building, I found a huge pile of empty pods and winter-pea seed coats. (The opposite of a scatter-hoarder, the Norway rat stores all its seeds in one place and is known in biology circles as a “larder-hoarder.”)