The Truth (2 page)

Authors: Terry Pratchett

“It was a week before Mr. Passmore was able to walk again, though,” said William. The case of Dibbler’s

second

customer had been very useful for his newsletter, which rather made up for the two dollars.

“I wasn’t to know there really

is

a Dragon of Unhappiness,” said Dibbler.

“I don’t think there was until you convinced him that one exists,” said William.

Dibbler brightened a little. “Ah, well, say what you like, I’ve always been good at selling ideas. Can I convince you the idea that a sausage in a bun is what you desire at this time?”

“Actually I’ve really got to get this along to—” William began, and then said, “Did you just hear someone shout?”

“I’ve got some cold pork pies, too, somewhere,” said Dibbler, ferreting in his tray. “I can give you a convincingly bargain price on—”

“I’m sure I heard something,” said William.

Dibbler cocked an ear.

“Sort of like a rumbling?” he said.

“Yes.”

They stared into the slowly rolling clouds that filled Broad Way.

Which became, quite suddenly, a huge tarpaulin-covered cart, moving unstoppably and very fast…

And the last thing William remembered, before something flew out of the night and smacked him between the eyes, was someone shouting, “Stop the press!”

The rumor, having been pinned to the page by William’s pen like a butterfly to a cork, didn’t come to the ears of some people, because they had other, darker things on their mind.

Their rowboat slid through the hissing waters of the river Ankh, which closed behind it slowly.

Two men were bent over the oars. The third sat in the pointy end. Occasionally it spoke.

It said things like, “My nose itches.”

“You’ll just have to wait till we get there,” said one of the rowers.

“You could let me out again. It really itches.”

“We let you out when we stopped for supper.”

“It didn’t itch then.”

The other rower said, “Shall I hit him up alongside the —ing head with the —ing oar again, Mr. Pin?”

“Good idea, Mr. Tulip.”

There was a dull thump in the darkness.

“Ow.”

“Now no more fuss, friend, otherwise Mr. Tulip will lose his temper.”

“Too —ing right.” Then there was a sound like an industrial pump.

“Hey, go easy on that stuff, why don’t you?”

“Ain’t —ing killed me yet, Mr. Pin.”

The boat oozed to a halt alongside a tiny, little-used landing stage. The tall figure who had so recently been the focus of Mr. Pin’s attention was bundled ashore and hustled away down an alley.

A moment later there was the sound of a carriage rolling away into the night.

It would seem quite impossible, on such a mucky night, that there could have been anyone to witness this scene.

But there was. The universe requires everything to be observed, lest it cease to exist.

A figure shuffled out from the shadows of the alley, close by. There was a smaller shape wobbling uncertainly by its side.

Both of them watched the departing coach as it disappeared into the snow.

The smaller of the two figures said, “Well, well, well. There’s a fing. Man all bundled up and hooded. An interesting fing, eh?”

The taller figure nodded. It wore a huge old greatcoat several sizes too big, and a felt hat that had been reshaped by time and weather into a soft cone that overhung the wearer’s head.

“Scraplit,” it said. “Thatch and trouser, a blewit the grawney man. I told ’im. I told ’im. Millennium hand and shrimp. Bugrit.”

After a bit of a pause it reached into its pocket and produced a sausage, which broke into two pieces. One bit disappeared under the hat, and the other got tossed to the smaller figure who was doing most of the talking or, at least, most of the coherent talking.

“Looks like a dirty deed to me,” said the smaller figure, which had four legs.

The sausage was consumed in silence. Then the pair set off into the night again.

In the same way that a pigeon can’t walk without bobbing its head, the taller figure appeared unable to walk without a sort of low-key, random mumbling:

“I

told

’em, I

told

’em. Millennium hand and shrimp. I said, I said, I said. Oh, no. But they only run out, I

told

’em. Sod ’em. Doorsteps. I said, I said, I said. Teeth. Wassa name of age, I said I

told

’em, not my fault, matterofact, matterofact, stand to reason…”

The rumor did come to its ears later on, but by then it was part of it.

As for Mr. Pin and Mr. Tulip, all that need be known about them at this point is that they are the kind of people who call you “friend.” People like that aren’t friendly.

William opened his eyes. I’ve gone blind, he thought.

Then he moved the blanket.

And then the pain hit him.

It was a sharp and insistent sort of pain, centered right over the eyes. He reached up gingerly. There seemed to be some bruising and what felt like a dent in the flesh, if not the bone.

He sat up. He was in a sloping-ceilinged room. A bit of grubby snow crusted the bottom of a small window. Apart from the bed, which was just a mattress and blanket, the room was unfurnished.

A thump shook the building. Dust drifted down from the ceiling.

He got up, clutching at his forehead, and staggered to the door. It opened into a much larger room or, more accurately, a workshop.

Another thump rattled his teeth.

William tried to focus.

The room was full of dwarfs, toiling over a couple of long benches. But at the far end several of them were clustered around something like a complex piece of weaving machinery.

It went thump again.

William winced.

“What’s happening?” he said.

The nearest dwarf looked up at him and nudged a colleague urgently. The nudge passed itself along the rows, and the room was suddenly filled wall to wall with a cautious silence. A dozen solemn dwarf faces looked hard to William.

No one can look harder than a dwarf. Perhaps it’s because there is only quite a small amount of face between the statutory round iron helmet and the beard. Dwarf expressions are more

concentrated

.

“Um,” he said. “Hello?”

One of the dwarfs in front of the big machine was the first to unfreeze.

“Back to work, lads,” he said, and came and looked William sternly in the groin.

“You all right, Your Lordship?” he said.

William rubbed his forehead.

“Um…what happened?” he said. “I, uh, remember seeing a cart, and then something hit…”

“It ran away from us,” said the dwarf. “Load slipped, too. Sorry about that.”

“What happened to Mr. Dibbler?”

The dwarf put his head on one side.

“Was he the skinny man with the sausages?” he said.

“That’s right. Was he hurt?”

“I don’t think so,” said the dwarf carefully. “He sold young Thunderaxe a sausage in a bun, I do know that.”

William thought about this. Ankh-Morpork had many traps for the unwary newcomer.

“Well, then is Mr.

Thunderaxe

all right?” he said.

“Probably. He shouted under the door just now that he was feeling a lot better but would stay where he was for the time being,” said the dwarf. He reached under a bench and solemnly handed William a rectangle wrapped in grubby paper.

“Yours, I think.”

William unwrapped his wooden block. It was split right across where a wheel of the cart had run over it, and the writing had been smudged. He sighed.

“’Scuse me,” said the dwarf, “but what was it meant to be?”

“It’s a block prepared for a woodcut,” said William. He wondered how he could possibly explain the idea to a dwarf from outside the city. “You know? Engraving? A…a sort of very nearly magical way of getting

lots

of copies of writing? I’m afraid I shall have to go and make another one now.”

The dwarf gave him an odd look, and then took the block from him and turned it over and over in his hands.

“You see,” said William, “the engraver cuts away bits of—”

“Have you still got the original?” said the dwarf.

“Pardon?”

“The original,” said the dwarf patiently.

“Oh, yes.” William reached inside his jacket and produced it.

“Can I borrow it for a moment?”

“Well, all right, but I shall need it again to—”

The dwarf scanned the letter a while, and then turned and hit the nearest dwarf a resounding

boing

on the helmet.

“Ten point across three,” he said. The struck dwarf nodded, and then its right hand moved quickly across the rack of little boxes, selecting things.

“I ought to be getting back so I can—” William began.

“This won’t take long,” said the head dwarf. “Just you step along this way, will you? This might be of interest to a man of letters such as yourself.”

William followed him along the avenue of busy dwarfs to the machine, which had been thumping away steadily.

“Oh. It’s an engraving press,” said William vaguely.

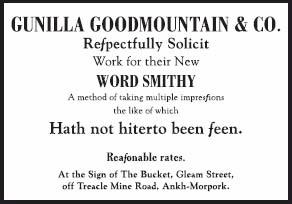

“This one’s a bit different,” said the dwarf. “We’ve…modified it.” He took a large sheet of paper off a pile by the press and handed it to William, who read:

“What do you think?” said the dwarf shyly.

“Are you Gunilla Goodmountain?”

“Yes. What do you think?”

“We—ell…you’ve got the letters nice and regular, I must say,” said William. “But I can’t see what’s so new about it. And you’ve spelled hitherto’ wrong. There should be another

H

after the first

T

. You’ll have to cut it all out again unless you want people to laugh at you.”

“Really?” said Goodmountain. He nudged one of his colleagues.

“Just give me a ninety-six-point uppercase

H,

will you, Caslong? Thank you.” Goodmountain bent over the press, picked up a spanner, and busied himself somewhere in the mechanical gloom.

“You must have a really steady hand to get the letters so neat,” said William. He felt a bit sorry that he’d pointed out the mistake. Probably no one would have noticed in any case. Ankh-Morpork people considered that spelling was a sort of optional extra. They believed in it in the same way they believed in punctuation; it didn’t matter where you put it, so long as it was there.

The dwarf finished whatever arcane activity he had been engaged in, dabbed with an inked pad at something inside the press, and got down.

“I’m sure it won’t”—

thump

—“matter about the spelling,” said William.

Goodmountain opened the press again and wordlessly handed William a damp sheet of paper.

William read it.

The extra

H

was in place.

“How—?” he began.

“This is a very nearly magical way of getting lots of copies quickly,” said Goodmountain. Another dwarf appeared at his elbow, holding a big metal rectangle. It was full of little metal letters, back to front. Goodmountain took it and gave William a big grin.

“Want to make any changes before we go to press?” he said. “Just say the word. A couple of dozen prints be enough?”

“Oh dear,” said William. “This is

printing,

isn’t it…”

The Bucket was a tavern, of sorts. There was no passing trade. The street was, if not a dead end, then seriously wounded by the area’s change in fortunes. Few businesses fronted onto it. It consisted mainly of the back ends of yards and warehouses. No one even remembered why it was called Gleam Street. There was nothing very sparkling about it.

Besides, calling a tavern the Bucket was not a decision destined to feature in Great Marketing Decisions of History. Its owner was Mr. Cheese, who was thin, dry, and only smiled when he heard news of some serious murder. Traditionally he had sold short measure but, to make up for it, had shortchanged as well. However, the pub had been taken over by the City Watch as the unofficial policemen’s pub, because policemen like to drink in places where no one else goes and they don’t have to be reminded that they are policemen.

This had been a benefit in some ways. Not even licensed thieves tried to rob the Bucket now. Policemen didn’t like their drinking disturbed. On the other hand, Mr. Cheese had never found a bigger bunch of petty criminals than those wearing the Watch uniform. He saw more dud dollars and strange pieces of foreign currency cross his bar in the first month than he’d found in ten years in the business. It made you depressed, it really did. But some of the murder descriptions were quite funny.

He made part of his living by renting out the rat’s nest of old sheds and cellars that backed onto the pub. They tended to be occupied very temporarily by the kind of enthusiastic manufacturer who believed that what the world really, really needed today was an inflatable dartboard.

But there

was

a crowd outside the Bucket now, reading one of the slightly misprinted posters that Goodmountain had nailed up on the door. He followed William out and nailed up the corrected version.