The Tunnel of Hugsy Goode (10 page)

Read The Tunnel of Hugsy Goode Online

Authors: Eleanor Estes

Tornid and me listened enthralled to this tirade of the moms, who are always worth listening to. Tornid's dad didn't even know it was raining out. He was baking a cakeâhe's good at that, and pies, especially lemon. So, everything being snug harbor inside, no dad needing rescue, Tornid and me went back out into the hard rain. Lots of Alley children were out now, and tiny ones took off their red sneakers and watched them race away. It was about as good as the blizzard last March.

Connie Ives came along. She'd thought it was hailing, the rain banged so on the windowpanes. She was barefoot, too, like us. Connie's hair is long and blond. But in a second it was as dark brown as shiny wet seaweed. She laughed and screamed. Connie enjoys things so much, you can't help but watch her. She licked the rain off her cheeks, and her eyelashes were stuck together and blacker than ever ... looked like fake ones. It's lucky that girls get into that stage finally and outgrow Contamination.

WeâBlue-Eyes, Black-Eyes, all Fabians, all Carrollsâcareened into each other. I said to Tornid, "The rain washes off the Contamination, so you can breathe in the presence of

grils.

"

The two stranger girls watched all this from their dining-room window. "Come on out!" yelled Blue-Eyes and Black-Eyes. All the Fabians have a friendly streak. But the two stayed in.

Suddenly I remembered! "Tornid," I said. "We should have stopped up the hole we made down there into the tunnel. The river will pour down there. Yikes!"

"Yikes!" said Tornid.

Too late now. What would we see tomorrow when we lowered ourselves down? A river? An under-the-Alley river? Yikes!

Midnight River on Larrabee Street

River! I mean it! Call the rain river in the Alley a river? Listen to this if you want to hear about rivers! In the middle of the night I waked up. Steve waked up. The entire family including my mom and dad waked. What did we hear? It didn't sound like rain. It sounded like a waterfallâNiagara, Victoriaâor like a vast river, the Mississippiâsomething gigantic whooshing and swooshingâlike the roaring Rio Grande.

We got out of bed, raced downstairs, and looked out the front windows. There was a flood, a real river on Larrabee Street racing along a mile a minute. It didn't come into our street, Story Street, which slopes down into Larrabee. It tore down Larrabee toward Gregory as though it just had to make the green light there. Rushing to the upstairs back windows, we saw that the river made a left turn on Gregory and whooshed itself around the corner ... because Larrabee begins to go uphill there.

It wasn't a temporary river that came and went like a lost river might do. It kept on coming and churning. My mom and dad got dressed. "Oh, dear," said my dad. "And I only just got to sleep..." Some grownups don't like something novel like a river on Larrabee Street. My mom had the baby in her arms. Holly spoke only in whispers to man and child alike because of the unusualness of the occasion. We all put on something and went out front and stood on the porch.

All the neighbors were coming out in strange garb, and some walked toward the wrought-iron gate of the fence that encircles the campus. Mrs. Stuart had curlers in her hair and didn't care and went to the gate, too.

Then Tornid's mom came to the Alley gate, saw us on our porch, and said, "Why don't you all come into our house? You'll have a better view. All the kids are up and looking out the front windows."

We did this. "It's a come-as-you-are party," said Tornid's mom. The moms and dads had some coffee, and the moms exchanged witty remarks about the way people outside were dressedâMr. Stuart in his fishing boots, for instance. The moms were making a party out of the occasion. It was like New Year's Eve. But no one played the piano or sang "Auld Lang Syne" because they had to watch the river.

There wasn't any end to this river. It came and came and rose higher and higher and swooped over the sidewalk. It might come through the Fabians' front door and go out the back and join up with the ponds created by the rains. Then this little group of houses at the top of the Alley T would be marooned. Tornid stayed close to his dad, ready to save him, if necessary. This was something! We all had sodas. "Rot your teeth," said my mom, but she gave in, for just this once, there being no cider in the house or juice.

Now, there was Mr. Stuart in his fishing boots, joined by John Ives, who, unlike my dad, loves anything exciting. If there isn't any excitement going on, he makes some. He rants about something. He was barefoot and had his trousers rolled up like a clammer. They started to wade across the raging river. "John, come back, come back," yelled Jane Ives. And Connie said, "Dad

dee!

"

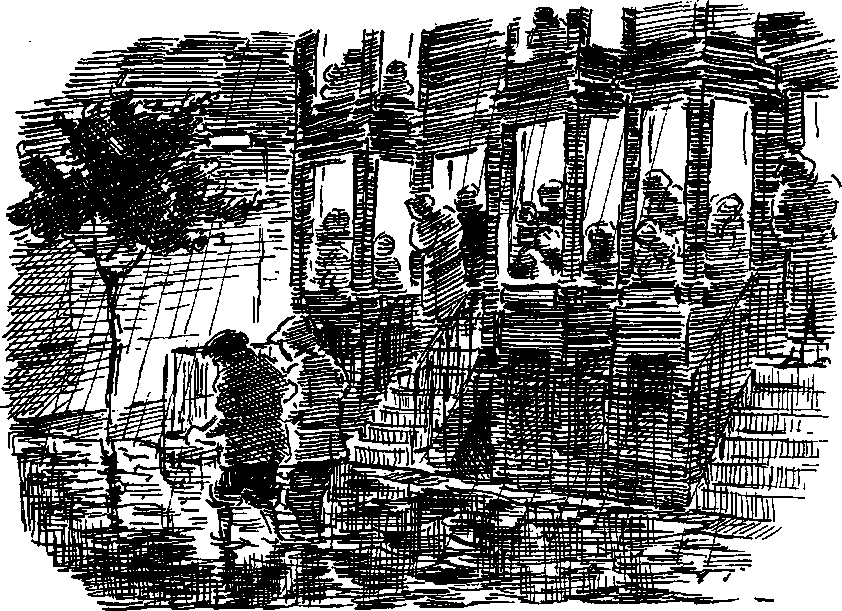

But they went anyway. And Connie and Jane Ives came into Tornid's house and joined all of us at the windows. Other neighbors came in, and if there had been food, a different dish brought by each different mom, it would have been like potluck days of olden times in the Alley. We saw John Ives and Mr. Malcolm Stuart make it across the river and be safe on the other side. They were joined by some students from the dormitory, and all disappeared up Larrabee Street to see where the river was coming from. After a while they came back, sopping wet and exhausted. They came in Tornid's house, and this is what they said.

John Ives said, "A water main broke up there at the corner of George and Larrabee. The houses on, and next to, the corners may crumble. God's blessing no car was coming along at the moment of the break. But cars parked near the corners were whooshed up into the air ten feet and landed upside down, on lawnsâanywhere. Poor Mrs. Allessandro, my secretary ... I helped evacuate her. People are still being evacuated. Some had to be guided from rooftop to rooftop. The students helped me and Malcolm rescue fainting ladies and carry them to safety. A person on George Street had gotten a rowboat out of his cellarâwhy anyone has a rowboat in his cellar in Brooklyn beats me, but that's Brooklyn for you ... full of surprises as well as churches..."

John Ives was happy and excited. He's a great storyteller. Sometimes he shouts. It comes down in his family, Jane Ives says, telling stories well, from generation to generation. His grandfather had the gift, his mother, and now Connie herself ... that's three generations right there. "A magnificent sense of drama," says Jane Ives about them all. But not now ... she isn't saying that now. Now, she is listening as we all are to the account of the flood.

Mr. Stuart said, "Sure was awful. Terrible. Roaring river." He never says very much.

John Ives was speaking again. "And don't let anyone say one thing against our students. They were right there, right on the spot, before police, firemenâanyone.

They

made trips into houses,

they

rescued children and the aged and carried them to a judge's house, an uncle of poor Mrs. Allessandro's, over near Myrtle.... I am very proud of them, our students, very proud," he said.

Mr. Stuart spoke. "Yes, indeed. Proud."

John Ives said, "I won't hear to anybody running down our students ... those with beards and those without. Art students, architecture, food sciences..."

Mr. Stuart spoke. "Hm-m-m ... didn't see any from science..."

Mr. John Ives said, "Oh, yes there were, Male ... you don't have to worry about your own students. They were there, too, along with all the other students, from all the schools, from all the dorms and houses around here, barefooted, pants and pajamas rolled up, rescuing people right and left, handing little ones and frail old ones out windows, carrying them on a man-made chain across the gushing water. They were heroic."

Mr. Stuart spoke. "Heroic."

Mr. John Ives said, "Where they got that rowboat ... beats me. Ingenuity. That's what our students have. And I want you to know that I've worked on campuses all over the country ... north, south, east, and west, even England ... and I have never met a finer bunch of students than ours here at Grandby College. Dedicated. They rise to an occasion.... God's blessing ... a miracle ... that no one was driving down Larrabee. That would have been the end of him ... whoo-oosh him up in the air. He'dâthey'dânever have survived."

Mr. Stuart spoke again. "Never. Pretty bad ... killed ... sure.... Might have been. You never know."

Loud and clear John Ives said, "Yes, we can be proud of our students all right. Fine chaps. Who's responsible for an accident of this sort? Water! What a waste of good water! Think of the drought of the past two summers, and we might, in spite of the two inches yesterday, have another this summer ... reservoirs still low.... How we have saved water ... not bathed ... not watered the grass (look at the grass on the campus!âburnt tan already and it's not even June). Drought! Yet they let this water come pouring out of a faulty main that they should have known about and fixed long ago. Now they can't even locate the break ... where it is. Ts! And where's it all going, our good water? Roaring down Larrabee. Can't even get into the drains. Poor Mrs. Allessandro ... she's my secretary ... one of those who fainted.... She'll move, she'll move ... and then where'll I be without a secretary?"

Sasha licked Mr. John Ives's feet.

But he went on in his peppery southern way. "'Politics. Politics, politics, child. Politics.' That's what my mother always used to say when the price of cotton fell...'It's politics, child. Politics.'"

We were getting sleepy. All the sodas gone, we drank water from the faucet to have some before it all rolled away, until my mom said maybe we should boil it first. But we were enthralled by Mr. John Ives. It was like being on the banks of the River Kwai, I thought.

John Ives said, "You'd think someone in the Water Department or Con Ed would have a map showing where the bungs are so they could turn them off. Efficiency? Never mind. Let's pray ... pray that our fine new mayor will get things running right..."

I said to Tornid in a whisper, "They should draw a map or plan of the under-Brooklyn like we have of the Alley and then go and find the bungs.... If they don't know, they could at least guess..."

Mr. Malcolm Stuart said with gloom, "I dun-no-o."

While warming his feet on Sasha, Mr. Ives said, "At least our mayor is an honest mayor. He was even on the spot just now. I saw him. I was helping poor little Mrs. Allessandro out. Someone said the mayor was going to bung up the leak like the boy did in 'The Leak in the Dike.' Some sarcastic remark made by some wise guy, the sort that blames the mayor for everything including snow."

I like the mayor, too. I wondered if he had come across the river by helicopter. Perhaps he hadn't even read my letter yet with all these floods and fires and other terrible things to go to.

Mr. John Ives went to the window. "My golly!" he said. "There he is again, the mayor!"

"John Ives must have ESP, too," I whispered to Tornid.

Everyone crowded to the window and rapped and waved. In spite of the rushing noise of the water, the mayor heard us and he waved back. He had his pants rolled up like John Ives and might be barefooted, likewise. After that, everybody went home to their own houses and to bed because the water stayed at about the same level and wasn't coming through anyone's front door.

Next morning everybody felt like the day after New Year's Eve. Some took medicine. But the river had stopped. They got it stopped at 6:00

A.M.

, the radio said. There were some pictures in the

Times.

You could see John Ives and Mr. Malcolm Stuart with his fishing boots on. Also the mayor shaking hands with Father Hanley, the minister of the church at the corner of Gregory. He had a pot of coffee in his hand and some paper cups and was sitting on the seesaw in the park opposite Tornid's.

It was Saturday. Tornid and me looked at the mess left on Larrabee Street for a while. Pebbles, beer cans, sand, rubble, old tires, burnt tin cans from some incinerator! John Ives was out there again, this time trying to help clean up some of the mess. He can't stand messes like this and was muttering to himself. Even on non-mess days he stomps way across the campus to pick up some litter someone has littered. "Eyesore," he says. Once John Ives got out a newspaper all by himself named

The Grandby Growl.

In it he raged about things that are wrong on the campus, because the real college newspaper named

The Grandby Owl

does not rage hard enough for him. Now he's probably working up his rage enough to get out

The Grandby Growl

again ... vol. 1, no. 2.1 hope so.

I said, "Tornid, once we get down in the tunnel, we can get out a newspaper in the office that may be under Jane Ives's house, name it

The Tunnel Trumpet.

"

"Or

The Underground Gazette

," said Tornid.

"

¿Quién sabe?

" I said.

"

Sabe,

" he said. "We can write about the river in it," he said.

The river had been fun while it was going on. Too bad it couldn't stay always.

"But now, Torny, old boy, old boy," I said. "On with Operation Tunnel."

Trats

So, back to the hidey hole! Well. Right now the hidey hole was one big mush hole, water seeping into it from the marsh the Fabians' yard had turned into. I said to Tornid, "If Hugsy Goode still lived here, he'd probably plant water lilies and put polliwogs in."