The Two of Us (3 page)

Authors: Sheila Hancock

Immediately after the broadcast the heart-sinking, swooping howl of the siren warned of an air-raid. Panic. My father frantically

pushed myself, Billie and Mummy down the garden and ordered us to sit in the wet hole while he single-handedly dragged the

final railway sleepers across. He then, in a frenzy, shovelled earth on top. The stones rained in on us in the darkness and

for the first time in my life I saw my mother nakedly weeping. ‘Not again. Oh Christ, not again.’

Mass evacuation started. There was the possibility of us going to America, but when Dad heard that the little Princesses were

staying put in London he decided so would my sister and I. My father was put on secret work for Vickers and joined the ARP,

whilst my mother continued to work at the shop. Business as usual. Even the local police station had a notice saying ‘Stay

good. We’re still open.’ Blackout went up in all the windows and the world went dark. ‘Put that light out,’ shouted my dad

in the street. Slogans like ‘Keep it dark. Careless talk costs lives’, ‘Dig for victory’, ‘Be like Dad. Keep Mum’ (excuse

me?) and ‘Is your journey really necessary?’ became common currency. The Germans, and later the Japs, became objects of our

ridicule. ‘We’ll get the Hun on the run’ and jokes about Hitler’s one ball were rife, even among us kids. Humour was our only

weapon against an all-powerful enemy. That and Churchill.

10 February

The Tories have taken to standing Hague on a soapbox

and letting him loose amongst the people. Only trouble is,

in the newspaper photos, the people listening look bemused

and bored.

In contrast to our ribaldry, Winnie’s rhetoric was superb. We all crowded round our wirelesses when he was on. ‘I have nothing

to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.’ I found him much more exciting than Laurence Olivier or James Mason. He was the

best actor of the lot, sounding as if he really believed what he said. His gift for oratory got us through that well-nigh

hopeless situation. I saw how my parents perked up and set their jaws after he spoke. ‘Let us therefore brace ourselves to

our duty, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Commonwealth and its Empire lasts for a thousand years, men will still

say, “This was their finest hour.”’ The British Empire has not lasted a thousand years, and as the people who experienced

the war die off, few recall how fine was the hour, but young as I was, I do.

When the Battle of Britain started we were situated in Bomb Alley between Woolwich Arsenal, Vickers and the City and docks.

We were the defence area. Down our road were black cylinders that produced a smoke screen, on the waste land behind our garden

were a mobile searchlight and an ack-ack gun that split your eardrums. Above in the sky were hundreds of barrage balloons

into which the more dimwitted Germans were meant to collide, I suppose. Concrete blocks appeared across the roads confidently

intended to stop the German tanks.

My sister, mother and I slept every night on bunks in our now completed 6 feet 6 inches by 4 feet 6 inches Anderson shelter,

the bangs and shudders not disturbing my sleep at all. My main fear was that a German airman might be shot down in our garden,

but I slept with my hand on the spanner for the escape hatch to deal with that. I still sleep with one hand above my head.

Occasionally someone would say after a huge bang, ‘That was close,’ and peer out to see if the house was still standing. We

were lucky. It always was – just. The roof went several times and most of the windows; eventually, my father gave up repairing

them and just covered things up with tarpaulin and planks of wood.

Come daylight, we went to school in a crocodile, with tin helmets and gas masks at the ready. On arrival, we went down more

shelters. Long corridors, underground, with benches either side. Here we did our lessons, but if the air-raid got very close

and noisy it was my chance to shine. Lessons were stopped and as a distraction I was allowed to entertain. I must have been

the only person in Bexleyheath who wanted the bombs to fall nearby. I puzzled my young audience with impersonations of Ciceley

Courtnidge, Evelyn Laye and Suzette Tarrie – none of whom I, and they, had ever seen, but my sister had been in a panto with

the impressionist Florence Desmond and I impersonated her impersonations of them. I had heard little Julie Andrews and Petula

Clark on the wireless and I had a go at them, although my Andrews coloratura was a bit of a liberty.

14 February

Valentine’s Day. John gave me an odd-looking teddy bear

to add to my collection. He says it looks like him – grumpy

with little short legs. It does give a familiar anguished bleat

when you press its tummy.

We stuck out this mole-like existence, as usual making the best of a bad job. I competed with my friends for the finest shrapnel

collection. Pieces of a bomb were prized, as were machine-gun bullet cases. We were still in imminent threat of invasion.

In June 1940 the French surrendered to Hitler in the same railway carriage in Compiègne where General Foch had made the Germans

agree to humiliating terms in the armistice of 1918, so Hitler was just across the Channel, photographed dancing with glee.

We were not overly confident that the Home Guard marching down the street with rusty old rifles and pikes and cutlasses from

the local museum would be able to beat back the Hun. There were dog fights overhead night and day, bomb sites everywhere and

friends being killed. The Spitfires dodged and weaved above our heads, puffing shots at the relentless 1,000 bombers a day

that came over Britain. ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.’

In December 1940 the City of London was ablaze and on 11 May 1941 there was a raid in which 1,400 people died. In one night

all the buildings that represented our way of life were struck: The British Museum, Westminster Hall and Abbey, Big Ben, the

House of Commons, St Paul’s, all the railway stations and Buckingham Palace. For the first time, people were weeping in the

streets. Enough was enough. It was agreed that my sister and I should be evacuated to the country. I had no idea where.

As I stood in a shattered King’s Cross Station, clutching my suitcase and gas mask, I thought I was being sent away for ever.

The station was full of people in uniform. Nearby was a group of Navy officers, showing off to a couple of Wrens in their

jaunty tricorn hats.

‘Where’s the bloody train?’

Dad whispering, ‘You see, girls, gents like that can get away with swearing. It sounds all right in a posh voice, but you

mustn’t do it.’ He continued to run desperately through a crash course of defensive behaviour:

Little girls should be seen and not heard.

Blessed are the meek.

Don’t blow your own trumpet.

Keep yourself to yourself.

Keep out of trouble.

By the end of it I was convinced the country was the Dragon Wood, and I was no St George. I was an eight-year-old girl, with

a solid rock in my chest and a huge lump in my throat. The train steamed in and my fifteen-year-old sister dragged me away

from my father. We undid the leather strap of the window in the corridor. He shouted through it, panicky, ‘Bum Face, what’s

your identity number again? In case you get lost.’

‘CJFQ29 stroke 4.’

As the train chuffed out of the station I saw my father bent over, his hands on his knees, head hanging down, unable to look

at us as we disappeared waving, weeping.

26 February

Sweet ceremony in Oxford giving Colin Dexter the freedom

of the city. After we had a romantic meal and a night at

the Manoir aux Quat’ Saisons. We were like a couple of

kids. Agog at all the luxury, you’d think we’d be used to

it by now but we still feel they might turn us out if we

misbehave. Which we did in the privacy of our luxury suite.

My sister and I were billeted in Wallingford, then in Berkshire later to be transplanted into Oxfordshire, on an old couple

called Mr and Mrs Giles. They had no children but doted on a snuffly Pekinese called Dainty, who rode in the basket of Mrs

Giles’s sit-up-and-beg bicycle. Dogs they understood. Children were a mystery. The big girl was OK, pretty and self-possessed,

but the little ’un was a puzzle. I was painfully thin on wartime rations, monosyllabic with despair, face contorted with a

tic. Every few minutes my mouth gaped wide open and described a circular movement. Then my teeth clamped shut into a tight

grin and my shoulders shrugged up to my ears. It made me look demented. Trying to comfort me, Mrs Giles made little egg custards

from real eggs. I had only had dried eggs since the war started. Too frightened to refuse one, I forced the slippery pale

yellow spoonfuls down my contracting throat. Half an hour later my stomach dissolved. I was given a torch and made my way

down the garden path to a hut at the end. Inside was a hellhole. A black pit over which was a scrubbed wooden seat. My feet

could not touch the ground and I clung to the sides, vomiting now as well. My bottom was much smaller than the hole, I could

disappear and never be seen again. Or alternatively be bitten by the tarantulas hanging above my head. I cleared up my sick

as best I could by torchlight with the neatly cut squares of newspaper that hung from a piece of string on the door. The endless

path back to the house, surrounded by pitch blackness, was definitely the heart of the Dragon Wood.

I was settled in for the night on an old brown leatherette settee. Everyone else went upstairs. The latch of the wooden door

at the foot of the stairs clunked shut. I stared out of the window at the stars, begging them to watch over my mum and dad.

As I lay there, the pillow either side of my face became wet with tears although I dared not make a sound. Then I felt a warmth

in the bed. I had soiled it. Like a baby. I lay unable to move or speak to ask for help, my cosy world disintegrating. The

Blitz had been fun but this strange country world was dreadful.

My sister Billie soon went back to London to pursue her dancing career, dodging the bombs in London and all over England on

tour. Later she joined ENSA (the Entertainments National Service Association) and weaved between torpedoes to Africa, where

she ventured into godforsaken places to brighten up the troops. She was fifteen when she started, so she grew up fast. I worshipped

her. She was so glamorous in her uniform and she and her variety friends were outrageous and funny. This separation from her

and the rest of the family was grievous. I knew there was a very good chance they would be killed in the inferno I was leaving

behind.

1 March

Taking a break in France before

Peter Pan

. Stopped off at

Vasaly on the way down to Provence. I wanted to climb

the steep hill to the church to light a candle for Jack who

is having his brain scan check-up today. We passed an

ancient building on which was a plaque which said some

saint had stopped there on his journey and founded this

hospice on the site. John struggled on a bit, panting, then

sat on a stone, lit a fag and said, ‘I think I’ll stay here and

found a hospice if you don’t mind, kid.’ I snarled, ‘Well, I

hope it’ll be a non-smoking one,’ and went on to the top.

He’s nine years younger than me, for God’s sake.

IN THE YEAR OF John’s birth all the church bells rang. Up until then they had been silenced, only to be rung when Britain

was invaded, but a victory at El Alamein in 1942 marked a turning point in the war, and Churchill ordered the bells to celebrate

it. But, always brutally honest, he warned, ‘This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps,

the end of the beginning.’

1942 did, however, mark the beginning of the life of the boy. On 3 January of that year, John Edward Thaw was born in Longsight,

Manchester.

Churchill was right to be cautious about premature rejoicing over El Alamein. In the same month as John’s birth, two ugly

events had illustrated that further horrors were being planned. Both prompted television programmes later in the life of that

baby, who was destined to become one of the medium’s biggest stars.

Reinhard Heydrich, right-hand man to Himmler, held a secret meeting in which a group of Nazis cold-bloodedly planned the extermination

of the Jews – the Final Solution. Sixty years later, Heydrich and his team’s clinical decision to set up gas chambers and

killing camps was chillingly portrayed by Kenneth Branagh and his fellow actors in

Conspiracy

. John, no longer able to perform himself, watched it with profound admiration.

The British also embarked on a programme of mass killing in the month of John’s birth. Bomber Harris decreed that his Bomber

Command force would ‘scourge the Third Reich from end to end’ with blanket bombing that had no specific military target but

was aimed at lowering the morale of the German people. With our modern approach of so-called clean bombs and avoiding collateral

damage this may seem shocking, but perhaps it is more honest. John’s portrayal of Bomber Harris on television in 1989 pulled

no punches but, with his usual empathy for the characters he portrayed, he made it easier to understand how the man and the

country felt, bearing in mind that simultaneously news came through of the slaughter of Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto. Hatred

was in the air. Into this grotesque world came the baby who had ‘the whitest hair and bluest eyes you’ve ever seen’.

His mother, born Dorothy Ablott, was one of ten children. His father, John Thaw, commonly known as Jack, was one of seven,

two of whom had died in childhood. They married when Dorothy was nineteen and Jack twenty. Their engagement party did not

bode well for the relationship of the two families. Aware that the Ablotts were even needier than they, Jack’s mother dispatched

her daughter Beattie with her fiancé Charlie on the long walk from their home in West Gorton to the Ablotts’ home in Longsight,

with a laundry basket full of crockery for the party. The party itself was an awkward affair as the families sized each other

up but all went reasonably well until the day after. Beattie and Charlie returned with the empty basket to collect the loaned

dishes. ‘You’re not touching them pots till she gets ’ere to see what’s what,’ said Mr Ablott, despite the obvious superiority

of the Thaws’ precious best china to their own.

3 March

Bought some pretty new plates in Marseilles plus a desk,

bookshelves and chair in flat packs from Habitat. John

cursing and growling in the salon trying to understand the

diagrams. I put World Service on loud and do a lot of

cooking. Eventually I am summoned to search for various

nuts and screws he’s lost and share his disgust at the ‘fucking

idiots who designed these things’. He is inordinately proud

of the slightly skew-whiff bookshelves and wobbly desk

and chair that he completed. I tightened a few nuts while

he was in the garden.

Dorothy’s father was a frightening man. A cripple from birth, he had a deformed hip and a shortened leg on which he wore a

hefty raised boot. In later life John too had a withered leg, which he put down to copying his grandfather’s walk, although

a more likely explanation was a neglected ankle injury from a car accident causing him to drag his foot and therefore under-use

his calf muscles. If Dorothy and her siblings were scared of their father’s physical violence, they doted on their mother.

A tiny woman, with several fingers missing on one hand from an accident at work with an industrial sewing machine, she managed

to keep the family going despite her husband’s brutality and habitual unemployment.

As a result of the engagement party débâcle, none of the Thaw family attended the wedding at St Cyprian’s Church round the

corner from the Ablotts’ house. Jack and Dorothy started married life in a rented house in Stowell Street, West Gorton. The

terraced rows of two-up, two-down houses had back-to-back cobbled yards with one outside lavatory shared by four neighbours.

Once a week, a thorough wash was done in a tin bath in front of the kitchen coal stove, the water shared to cut down on the

boiling of pans to fill the bath. Jack’s mother and father lived next door, his sister Beattie and her now husband Charlie

up the road, his sister Doris and her husband Mark on the opposite side. The Thaws ruled the roost in Stowell Street, especially

Jack’s mother.

Mary Veronica Mullen, Grandma Thaw, was an ebullient woman of Irish descent, fat and raucous and overflowing with energy.

On top of running her family she worked as a caterer in Hunter’s Restaurant during the day and at Belle Vue Pleasure Gardens

in the evening. She was a wonderful cook and fed anyone who was down on their luck with leftovers she brought home from work.

Every Christmas George Lockhart, the famous ringmaster in the annual Christmas Circus, chose to stay with her. One year an

entire Welsh Rugby Team, playing a Christmas match at Belle Vue, camped out in the various Thaw houses.

Mary Veronica thrived on work. On her marriage certificate, instead of the usual blank for the bride’s rank or profession

in that period, she is listed proudly as Grocer’s Assistant. Her husband is entered as an Iron Slotter, though sadly not a

lot of iron needed slotting and he was frequently unemployed. He could play any tune on the piano, a useful skill for a family

that enjoyed a good old sing-song. On one occasion during the war, Grandma Thaw was enjoying just such a knees-up in the local

pub when a buzz bomb cut through the roof and landed at the back, mercifully failing to explode. Everyone fled but Grandma,

who, surrounded by debris, refused to go till she had finished her Guinness.

I once caught John with tears in his eyes as he watched a TV performance of mine as the battling mother in D. H. Lawrence’s

Daughter-in-Law

, because I reminded him of his gran. She was a Catholic. Her husband disapproved, so she gave her children rather ambiguous

moral guidance by sending them secretly to the local monastery to buy holy water: ‘Don’t tell your dad.’ She fought many battles

against injustice for her neighbours, but was not best pleased when her small daughter was banned from the local football

ground for a month when she ran on to the pitch and beat up a player who had kicked her brother.

Into this rumbustious environment Jack brought his young bride. A feisty peroxide blonde, smart and knowing, she kept a clean

house and got on well with everyone. Perhaps too well with some. A year after the wedding their first son, John, was born.

10 March

The family arrive. This is a wonderful place for the grandchildren.

They can run wild. They play with the Romany

kids camping in the hameau – everyone plays boules with

the locals. We relish one another in the sun. How lucky

we are.

The war made it difficult to have a stable married life. Jack was exempt from military service as he had broken his spine

as a child, playing leapfrog over apple crates, so he worked making munitions in Fairey Aviation Factory, often working nights.

He was also a volunteer rescue worker with the Fire Brigade. After one raid his sister Beattie, who worked on a mobile canteen,

came across Jack crying and vomiting into the road, having just dug out of the debris a pair of child’s wellingtons with the

feet still inside.

Twenty-year-olds everywhere were exposed to horror but Dorothy still managed to have a laugh. She kept her son and everyone

else amused when she went down the public air-raid shelter in the nearby croft, but mainly they got under the table or the

stairs if there was a bad raid. She fell about when she heard that Beattie had refused to leave her new bedroom suite when

the bombs got close, resolutely holding on to the mirror until the planes passed over. In 1944 another son, Ray, was born.

At the same time Jack was sent to work in the mines and was away even more. It could have been worse. Many of their friends

who had been at the front were missing or killed in action.

The end of the war was greeted with great rejoicing. Ray and John attended street parties dressed in their MacDonald tartan

kilts in honour of their great-grandmother, called illustriously Flora MacDonald. The implications of the atom bombs on Hiroshima

and Nagasaki were not allowed to spoil their celebration at having, against all odds, got rid of something vile. Heedless

of the war-weariness of the grown-ups, Ray and John, now two and four years old, began to have the time of their lives.

11 March

Our dear friends David and Liz took us for a picnic right

up in the Luberon mountains at Silvergue. Magic.

With the war over, Belle Vue, just by Stowell Street, regained its former glory. Founded by John Jennison in 1836, it had

grown to be a wonderful pleasure garden for the working class. Sixty-six acres of it. John and Ray went to the speedway track

with their dad and mum. They watched the rugger and football, getting in free because Uncle Charlie was a coach. Sometimes

their dad, fag hanging from the corner of his mouth, would play football. They rode on the helter-skelter, the scenic railway

and the magnificent Bobs roller-coaster. There was an open-air ballroom alongside a lake for the grown-ups, where many a romance

blossomed. Young women in their Sunday best danced gracefully to Bonelli’s Band, hoping someone beautiful would have the last

waltz with them and walk them home. John’s mother got a job as a barmaid at the Longsight Gate where Grandma Thaw was still

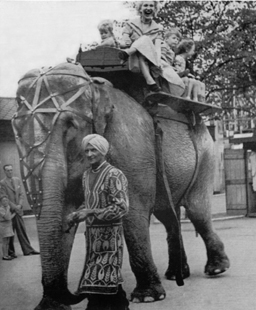

working as a cook. The zoo housed camels, lions, polar bears, tigers and monkeys. Phil Fernandez, the Indian elephant keeper,

lived over the road, and the two boys helped him march extra elephants through the street, from the station to the zoo, for

the annual circus. Young John became very fond of Ellie-May, mucking out her stall and having rides, clinging on to her huge

back. Very often the gibbons and monkeys escaped over the wall into the surrounding streets. The kids helped round them up

in nets. Belle Vue was their huge back garden.

John heard his first classical music when the great Halle Orchestra played at Belle Vue, as well as developing a life-long

passion for the brass bands he heard there. One year the magnificent annual pageant, culminating in a spectacular fireworks

display, was made doubly exciting when his father got a walk-on part. Jack always maintained that his role in the Belle Vue

pageant demonstrated the talent that he bestowed on his offspring. His delivery of his one line, ‘Seize that man’, dressed

in a toga, holding a spear, was apparently the talk of Manchester. His grandchildren later conceded, when he frequently re-created

his triumph for them, that his profile was acceptably Roman, but his accent less so. He challenged them to prove it was less

Latin than their posh English.

12 March

Lovely to be in France. Weather really hot. John slaving

to learn his lines for

Peter Pan

. He doesn’t have to, it’s a

broadcast, but he says pointedly, the live audience will be

short-changed if he has his head in the script. They’re not

paying anyway – so sod it, as far as I’m concerned. Asked

me how to pronounce ‘floreat Etona’, Hook’s dying

words. When I joked, ‘Why? Didn’t you learn Latin in

Burnage?’ he snarled, ‘We didn’t even learn English. Mind

you, we’d have rowed the arse off those Eton tosspots on

Belle Vue lake.’