The Two of Us (6 page)

Authors: Sheila Hancock

In the forties the grown-ups were still exhausted and dejected, despite the advent of the Welfare State, but the fifties saw

a surge of energy amongst the young. The new pop music became central to their lives. To begin with, John and his brother

and friends went to clubs in Manchester to hear Chris Barber, Jack Parnell, Ronnie Scott and the groovy Humphrey Lyttelton.

Then they became excited by skiffle and Lonnie Donegan. Along came Bill Haley, Little Richard and the British contingent of

Tommy Steele, Cliff Richard and Marty Wilde, who paved the way for the Beatles and the Stones. The age of the teenager had

arrived. Before, young people had to be seen and not heard, but suddenly they were all-important and going wild. A seminal

moment was Elvis Presley’s appearance on

The Ed Sullivan Show

where he swivelled his hips as if he were ‘sneering with his legs’ and the grown-ups decided he should in future be shown

only from the waist up. Young John thought him thrilling. An Elvis impersonation went into his act, slightly toned down for

the old people’s homes.

On the Belle Vue dance floor the old order fell apart. Sedate waltzes and quicksteps were replaced by jitterbug and jive.

Girls were flung about in wild abandon. The iconic 1955 portrait of Marilyn Monroe, standing on a grille with the draught

blowing her skirt up to reveal a glimpse of rather chaste knickers, was where it was at. On the tennis courts Gorgeous Gussie

Moran showed her frilly ones. Young John enjoyed all this.

5 June

John still not made doctor’s appointment. When I nagged

him he did his usual ‘Oh, never mind. Go on, show us

your knickers.’

The entertainment world led the public into a revolution. Anything goes. The Goons were anarchic and incomprehensible to the

older generation. Zaniness was unleashed: ‘See you later, alligator. In a while, crocodile.’ In his drainpipe trousers, huge

suede shoes with crêpe soles, floppy jumper and cravat and sporting a long cigarette holder, a teenage John felt possibility

in the air. He wanted money so that, like Liberace had in 1954, he could say to his critics, and maybe his mother: ‘What you

said hurt me very much. I cried all the way to the bank.’

Look Back in Anger

opened in 1956 and when John read it, he recognised himself in Jimmy Porter. Film and theatre, although he had still only

seen variety shows, were his obsessions. TV was not part of his ambition. In 1955 the BBC was joined by ITV but John was not

one of the mere 340,000 in the country who owned a set. Olivier was his god. He spent hours listening to recordings of his

performances and delighting in the idiosyncrasies of his delivery.

6 June

Went to see Dr Grimaldi about John’s voice. Immediately

sent him over to Harley Street to see a specialist. He said

one vocal cord was frozen and ‘something’ was causing it.

He ordered a chest x-ray. What the hell is it? I am pretending

calm but I have a fearful foreboding.

Much as he wanted to act, he did not think it was a possibility. No one from his world went into the theatre. Instead, he

left school at fifteen and tried other things. His brother was doing well as an apprentice plumber but John was positively

dangerous with a soldering iron. He worked in the fruit market and nearly broke his back carrying sacks. He trained with a

baker but was appalled at the thought of a lifetime putting jam in doughnuts. He passed the preliminary examination to be

an electrician, but judging by his inability to change a light bulb without causing an explosion, lives were saved when he

progressed no further.

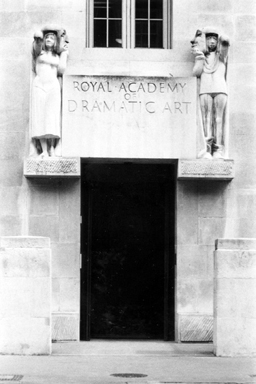

Even though he had left school, his teachers rode to his rescue, believing that acting was the path John should pursue. His

old headmaster, Sam Hughes, moved heaven and earth to wangle a grant from Manchester Council, should John succeed in getting

into RADA. It seemed unlikely that a boy from a council flat in Burnage, with an accent you could cut with a knife, could

enter those hallowed halls.

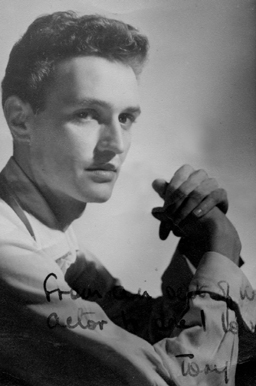

Finally John was summoned for an audition. The whole family got excited about it. Jack took a trip to the pawn shop to pay

for some quick elocution lessons and buy him a new suit. His Auntie Beattie accompanied John into Manchester for the important

purchase. She could not dissuade him from a complete teddy boy outfit, in which he thought he looked the bee’s knees. His

father expressed approval of it, despite grave misgivings, knowing how much bolstering his son needed to go to London for

the first time and face all those toffs. ‘Aye, lad, that’s very good. Very smart.’

At six on the morning of the audition Uncle Charlie drove up to Daneholme Road in his white van. Jack got into the front to

direct Charlie on the best route. Sandra and Beattie squashed up in the back to make room for Ray and John, taking care not

to crease his suit. Four hours later John clambered out in Gower Street. Beattie brushed the cement dust off his trousers

and he remoulded his duck’s arse hairstyle in the wing mirror. His knees buckled under him as he passed between the stone

figures of Drama and Comedy that flank the door of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. The others in the waiting room stared

at him like he was something from another planet. He realised his suit was not like theirs. The fashion was obviously different

down south. He was tempted to leave. It was all a big mistake. But how could he face that lot waiting in the van? A cocky

young man came out who’d obviously done well. ‘All you need is confidence. Look like you’re great and they’ll believe you.

Act it,’ he told the assembled auditionees.

All right. It was now or never. He had to have this. He could act. He knew he could. So come on – act being confident.

In the audition room was a row of half a dozen people slouching on wooden chairs. John marched in, acting confidence for all

he was worth. They all sat bolt upright. They looked impressed. Flabbergasted in fact. Good. He had chosen a speech from

Richard III

and he launched into his version, complete with humped back and a dramatic limp that owed as much to Grandfather Ablott as

Olivier, as did the malevolence. He could hear his careful elocution slip into Mancunian now and then but he saw them nudge

one another at his Olivier bits. Encouraged, he gave it all he’d got. They looked dumbfounded. When he finished they were

silent. Then one of them just said, ‘Thank you’ and he said, ‘You’re welcome’, and left. He told his family he thought he’d

got away with it. He had. Mercifully, the panel had been shrewd enough to see the potential of the strange lad.

7 June

Grimaldi told us baldly – the best way really – it’s cancer

of the oesophagus with secondaries to the lung. He had

already made an appointment with the best oncologist he

knew – Dr Slevin. We were reeling. John probably doesn’t

realise it’s the cancer Alec died of. We were incredibly calm

and polite – even laughed a bit. Outside Grimaldi’s door

we clung to each other, then someone passed us and we

were all polite again. Slevin, matter-of-fact, said he would

have to have a line put into John’s chest to take chemo

plus a big dose by injection in a clinic once a month. Did

he want to start today? John said he needed a weekend to

steady himself. Dear God.

MY PROFESSIONAL LIFE HAS been a litany of mistiming. I have always been ahead of or behind my time. Only in old age have I

caught up with myself. When I went to RADA in 1949 it was a finishing school for the rich, ruled over by a benign old buffer

called Sir Kenneth Barnes. Nine years before the invasion of Finney, Courtenay and Thaw. I was too early.

8 June

Went to Tarlton. Such happy memories. The stubby trees

we planted are an orchard now. The new building has

mellowed. It’s a lovely home. The visit seems to have made

John very positive. The world Alec and I, then John and

I, created has flourished. But I remember my poor skeletal

Alec there and was full of fear but I did an amazing performance

of utter confidence in the treatment. Labour won the

election. Tony’s done it again. Clever bugger.

In my time the Academy moulded its students into the elegant actors required for the theatre and film of the period, for which

I was not promising clay. TV, still in its embryo form, was not even considered. More important were the Radio Technique classes.

My childhood encounters with drama were the

Saturday

Night Theatre

plays and

Children’s Hour

, for which my family sat silently round our big brown wireless set. Radio was central to our lives. BBC English was the order

of the day. Wilfred Pickles was allowed to use his northern accent for his variety show

Have a Go

but went posh when he read the news. Women weren’t allowed to read the news at all. A BBC spokesman pontificated, ‘People

do not like momentous events such as war and disasters to be read by female voices.’

For most of the students of 1949, Received Pronunciation was no problem. All the Honourables and Lady Mucks spoke beautifully.

Most looked beautiful too. I did not even try to compete, slopping around in baggy cords, ex-Navy polo neck sweater and duffle

coat. The exquisite Eve Shand Kidd, huge blue eyes set in a piquant pixie face, caught me washing my face with soap. So horrified

was she that she bought me a complete set of Cyclax cleansing products as used by the Queen. I eyed these beauties with envy

in my soul. My early diaries, no,

all

my diaries are full of lamentations about my ugliness. An entry written when I was twelve reads: ‘Please God let me look all

right from the front.’ Meaning the front of house.

I was acutely aware that the West End theatre welcomed only pretty women. There would have been no room then for the unconventional

looks of a Juliet Stevenson, Fiona Shaw, Julie Walters or Zoë Wanamaker. They might have got character roles but not leads.

I was unfashionably tall, with bad skin and an odd nose. I compared unfavourably to Joan Collins in the canteen queue. Diane

Cilento looked a bit like me, but she was the pretty version. With natural white-blonde hair, green eyes and golden skin,

she was what I would have looked like if my prayers had been answered. I once saw her in the bath and was overcome by her

peachy loveliness. So presumably was Sean Connery, who later married her. In the sixties she played on film a part I created

with huge success on stage, and it seemed absolutely right and proper. In my diary I wrote: ‘News about Diane Cilento doing

film of

Rattle of a Simple Man

in press. Felt rather left out and sad but don’t blame them. How could I play it with this face?’

There were few men at the Academy. The death of so many in the war that had ended four years before, and the subsequent readjustment

period needed by those returning to Civvie Street, meant women far outnumbered the male students. It was considered an odd

profession for butch males. My first known encounter with a gay man was with Tony Beckley, at RADA on an ex-Navy grant. If

there had been any homosexuals in Bexleyheath, they kept it to themselves. They had to or they could have been sent to prison.

I didn’t know what they were. My mother didn’t till the day she died. She spent a lot of effort trying to find nice girls

for my gay friends to settle down with.

What little fun I had at RADA was with Tony and his friend Charles Filipes, later Charles Laurence, the playwright. Tony treated

the whole thing with merry contempt. Once, when late for an entrance as a servant in the marriage scene of

The Taming

of the Shrew

, he gaily informed the audience that he had been buying a new hat for the wedding. He had a ball. He managed to inveigle

himself into the Terence Rattigan party set – not difficult as he was devastatingly good-looking.

When being shown round Rattigan’s opulent Brighton house, champagne glass in hand, Tony broke the romantic spell by vomiting

in the marble bath with golden taps. He regaled our little gang with tales of his glamorous escapades over coffee at Mr Olivelli’s

restaurant round the corner from RADA. Sometimes several of us spent an afternoon at Lyons Corner House on Tottenham Court

Road, sharing a pot of tea for one and devouring bowls of sugar lumps while we applauded Ena Baga, entertaining on the electric

organ. We reserved stools in the morning for a place in the queue for the gallery that evening. We worshipped at the shrines

of Paul Scofield and Olivier. We discovered where Scofield went between matinees and his evening show and sat gazing in adoration

as he sipped his tea. Tony and I were both in love with him. We dreamed of future stardom and vowed that when we were old

we would retire to the actors’ home, Denville Hall, and be outrageous till we died. All his life Tony achieved outrage

par excellence

. He acquired cult status as camp Tony in

The Italian Job

and is now buried between Tyrone Power and Marion Davies in Hollywood. A more fitting end than an old people’s home for my

dear, flamboyant friend.

15 June

The first operation John has ever had in his life to put a

tube in his chest to put the chemo into his vein. I couldn’t

bear to see him laid out on the trolley but he smiled and

was so sweet to all the people tending him. Eventually home

with dozens of pills and potions.

I did my damnedest in classes to knock off my rough edges. I toiled at ballet and movement to control my ungainly height.

A ginger-wigged man, Mr Harcourt-Davis, who taught makeup, regarded me as a challenge. He decided to go for an orchidaceous

look, all slanting black eyeliner, white base and deep red lips. Startling but on the whole an improvement. I enjoyed Mr Froeschlen’s

fencing lessons. His cry of ‘Down, down lower, and

sit

’ to get us into the right stance is often repeated by RADA students of the period, especially in erotic situations. He praised

my thrusts and parries and I knew I looked good in tights. During one lesson I noticed two of the dishiest ex-service students,

Charles Ross and Peter Yates, who later became a film director, eyeing me intently. In the canteen they solemnly told me that

after dedicated research they deemed my legs, from the knees up, the best at the Academy. That was probably the single most

beneficial thing I learned at RADA – confidence in my thighs.

I had little in my voice after being subjected to the scrutiny of Miss King. Her cool, beautifully manicured hands stroked

my jaw, rigid with effort, and gently lowered my shoulders from under my ears. She ignored the giggles of my fellow students

as she tried to make me hear the difference between ‘door’ and ‘dawer’. She enlisted the help of the great Clifford Turner,

head of Voice Production. He suggested a tooth prop. This was an evil instrument shaped like a tiny dog’s bone, that was held

between the teeth in the centre of your mouth, with the object of opening up the vowels. I had it in my mouth for most of

my time at RADA.

16 June

Not a good start. I mix up the pills and give him an overdose

of one. The clinic reassured me on the phone but John

was pretty scathing about Sheila Nightingale.

My struggles with ‘the tongue, the teeth and the lips’, not to mention the ribs, the neck, the arms and the legs, did not

make me an easy person to share digs with. There were four of us in the room at the Young Women’s Christian Association in

Archway. My RADA friend Stella sympathised with my cater-waulings but the two other girls, not being actors, were less happy,

although they were content to share their clothes and food parcels from home. The rules were very strict. Doors were locked

after nine o’clock. In the evenings I was in a cabaret show written by an American fellow student, Dick Vosburgh – clever

material as befits the man who went on to be gag writer for many great comics including Groucho Marx and Bob Hope. I enjoyed

doing it. I also needed the money to augment my scholarship. I got in after hours through a window left open by my room-mates.

When I was caught there were no second chances. Christian women were not expected to stay out late.

Stella left with me, and the two of us found a room in St John’s Wood, which we shared with another RADA student called Gaynor.

We took it in turns to sleep on the camp bed, the floor or the sofa. We cooked in a black frying pan that festered over the

single gas ring. The landlord was a dodgy cove who employed us to sell his diamonds. We had to go into jewellery shops and

pretend we had broken off an engagement and needed to sell our rings. I was his star turn. I shamelessly wove a tale of physical

abuse and unwanted pregnancy that wrung tears out of jewellers from Hammersmith to Hackney. It was the best bit of acting

I did while at RADA and provided a lot of our rancid chips.

Necessity drove me into many jobs, which usually ended in the sack. I worked at a milk bar in Edgware Road, but Tony took

to inviting hordes of people to see me struggling with the froth machine in my large red-check hair bow that drooped over

my face in the steam. The owner did not appreciate them filling the place and only buying one Banana Heaven with eight straws.

Every Saturday I worked at the Archway Woolworth’s. At Christmas-time I was put on the card counter. When I was handed a fistful

of cards priced tuppence halfpenny, a penny farthing, threepence, three farthings, etc., I crouched behind the counter adding

up on my fingers while the customers bayed for attention. The avenging supervisor demoted me to the toilet roll counter where

one day I heard a perfectly projected, ‘Sheila Hancock, what

are

you doing?’ to which I elocuted back: ‘Earning a crust, Mr Clifford Turner.’

I waited on tramps and derelicts in the British Restaurant in Oxford Street, including one regular who claimed he was Jesus

and had holes in his hands and feet to prove it. I waited on the waiters at the Savoy in the staff kitchens, who vented their

hatred of the clientele on us. The performers and staff of Bertram Mills’ Circus were much more congenial. I was a showgirl

and usherette and had to prod the lions with a stick as they ran through a tunnel into the ring, to make them roar, otherwise

they would yawn all through the act after the hearty meal they were given before they went on.

One night we were told the Prime Minister was coming. The show had started when I noticed a lone man hiding in the shadows

at my entrance. Mr Attlee refused to go in during an act and disturb everyone, saying he was happy to wait and have a little

chat with me. Hard to imagine that happening with later prime ministers.

I grew very fond of the circus folk, admiring their camaraderie and vagabond life, and was tempted to stay, particularly when

I became friendly with a man who did a motorcycle wall of death act in a contraption up in the roof of Olympia. One night

his clown trousers caught in the wheel of his bike and I watched in horror as it spluttered to a halt. He floated down and

died at my feet on the edge of the ring. I left soon after.

20 June

Bloody hell. The press office say a journalist is sniffing round

about John. Advised to give a statement to get them off our

backs. I resent this. It’s like when I was ill. I don’t want

him to have to undergo this ordeal under the public spotlight

but I drew up a short announcement. The press are

usually pretty good if you are straight with them and they

know I, and particularly John, have never sought publicity

in a way that makes a plea for privacy hypocritical.

The nomadic circus life would have suited me. Having moved around all my childhood, I have never regarded one particular place

as home. During my RADA holidays and early career I often took off and travelled. Ahead of the times again, I was a hippy

before it was fashionable. In the late forties and early fifties, at every opportunity, I put a Union Jack on my knapsack,

which in those days so soon after the liberation of Europe opened all doors, and hitchhiked, finding work where I could. I

dug ditches in Holland to convert what had been a concentration camp into a holiday home for children. I washed up and waited

on tables in Paris. Young wanderers congregated on the steps of the Sacré Coeur and sang songs to a guitar. People willingly

gave us money and it didn’t feel like begging. I slept rough in haystacks and barns or stayed in primitive hostels. In Paris

I was delighted to discover a proper lavatory – I never enjoyed the holes in the ground – in the

Mona Lisa

gallery of the Louvre. As a result of my daily visits, I could write a paper on the beauty of La Gioconda. I stayed in Ibiza

when there were only a few artists and dreamers there and sat at the feet of Robert Graves in Deya in Mallorca.