The UltraMind Solution (86 page)

Read The UltraMind Solution Online

Authors: Mark Hyman

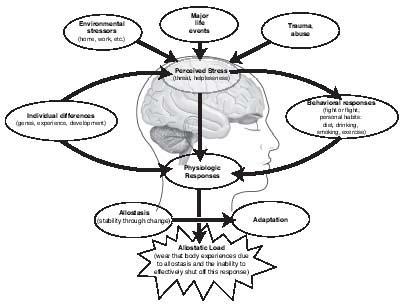

The problem in our culture is the chronic, unremitting, unrelenting stress and endless stressful inputs to our nervous system, including our nutrient-depleted toxic diet, environmental toxins, electropollution, and loss of a sense of control and community.

This puts us in a chronic state of alarm. In his book

The End of Stress as We Know It

, pioneering neuroscientist Bruce McEwen explains how chronic levels of stress lead to wear and tear on our systems. He calls this the “allostatic load.”

4

Think of it as the sum total of all the stressors on your system over a lifetime.

All of these excess stressors—stressors we were not designed to deal with on a chronic and repetitive basis—lead to overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system and stress response, followed by burnout.

Dr. Sapolsky has mapped out the way in which this chronic stress damages the brain. High levels of cortisol, the major stress hormone, damage the hippocampus.

When considered from an adaptive point of view, when we are in dangerous or stressful situations, we want to remember everything about it. That’s a good thing; it helps us avoid the situation in the future.

Figure 15: Allostatic load

That is why there are so many receptors for cortisol in the hippocampus, the memory center of the brain. Since we need to remember dangerous situations to avoid them in the future, our body is perfectly designed to help us do this.

However, in the modern world this system is overactivated. We don’t need to remember every situation we perceive as stressful. And high levels of cortisol over the long term injure the hippocampus, leading to impaired memory,

5

dementia, and depression.

6

Sonia Lupien from McGill University has also shown how stress shrinks the memory center and has damaging effects on our brain function and cognition.

7

;

8

Stress literally eats away at your brain.

The effects of stress can be seen quite clearly in those who suffer post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), an anxiety disorder that is the result of exposure to some traumatic event and causes the person who experienced the trauma to live in a state of hyperarousal. This condition affects about 15 percent of those who experience a major trauma such as war, violence, or abuse. It changes your brain and rewires your response to stress. Many who went through the trauma of 9/11 experienced PTSD.

9

Chronic stress has many negative effects on the body and mind that help explain the widespread problems with obesity, health, and brain function in today’s world. All the feedback from the body and the feed “down” from the brain works through the over or under activity of this important HPATGG system (the communication network that connects your brain with your entire body).

So any “stress,” whether it is physical danger, a thought, perception, toxin, allergen, infection, or even abnormal gut bacteria, has negative effects throughout this system. These effects are widespread and can be very powerful.

HOW THE BRAIN CONTROLS AUTOMATIC FUNCTIONS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here is a short list of the effects of an overactivated stress response over the long term.

10

I list these here just to show you the extent of the research and our understanding of how stress negatively affects us and our brains. Chronic stress over time:

Increases inflammation and inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, and Th1 immune response), which have all been linked to depression, bipolar disease, autism, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer’s.

Reduces the natural relaxation and anti-inflammatory calming, memory-enhancing neurotransmitter called acetylcholine.

Increases depression and anxiety.

Damages the hippocampus, leading to memory loss and mood disorders.

Increases “excitotoxicity” and activation of the NMDA receptors (the on/off switch for your cells) leading to cell death.

Reduces serotonin levels.

Reduces BDNF (the brain’s healing and repair factor necessary for the formation of new brain cells).