The Unimaginable Mathematics of Borges' Library of Babel (11 page)

Read The Unimaginable Mathematics of Borges' Library of Babel Online

Authors: William Goldbloom Bloch

Tags: #Non-Fiction

A form a

catalogue might take in principle is: Book (identifiers), Hexagon (location),

Shelf (only 20 per hexagon), Position on Shelf (only 32 books per shelf).

Perhaps surprisingly,

self-referentiality

is not a problem. A volume of

the catalogue, say the tenth, residing in Hexagon 39, Shelf 20, Position 14,

could well be marked on the spine "Catalogue Volume Ten," and

correctly describe itself as the tenth volume of the catalogue and specify its

location in Position 14, on Shelf 20, in Hexagon 39: there is no paradox.

However, beginning with the obvious, here are some of the difficulties that

arise.

Clearly, the

Library holds far too many books to be listed in one volume; any catalogue

would necessarily consist of a vast number of volumes, which, perversely, are

apt to be scattered throughout the Library. Indeed, reminiscent of the approach

of another ofBorges' stories, "The Approach to Al-Mu'tasim," and of

the lines in "The Library of Babel,"

To locate

book A, first consult book B, which tells where book A can be found; to locate

book B, first consult book C, and so on, to infinity. . . .

an immortal librarian trying

to track down a specific book likely has a better chance by making an orderly

search of the entire library, rather than finding a true catalogue entry for

the book. Every plausible entry from any plausible candidate catalogue volume

would have to be tracked down, including regressive scavenger hunts. An

immortal librarian would spend a lot of time traversing the Library,

ping-ponging back and forth between different books purporting to be volumes of

a true catalogue.

After

revealing the nature of the Library, the librarian notes that contained in the

Library are "the faithful catalog of the Library, thousands and thousands

of false catalogues, the proof of the falsity of those false catalogs, a proof

of the falsity of the true catalogue..." This, then, is the second problem

of any catalogue: the only way to verify its faithfulness would be to look up

each book. Furthermore, the likelihood of any book being located within a

distance walkable within the life span of a mortal librarian is, to all intents

and purposes,

zero.

Sadly, even if we were fortunate enough to possess a

true catalogue entry for our Vindication, presumably our Vindication would

merely give details of the death we encountered while spending our life walking

in a fruitless attempt to obtain the Vindication. (Recall in "The Library

of Babel," Borges describes Vindications as "books of apology and

prophecy which vindicated for all time the acts of every man in the universe

and retained prodigious arcana for his future.")

Let's

consider the first category of information found on library cards, that which

uniquely specifies the book.

Authorship is moot.

One might argue that

the God(s), or the Builder(s) of the Library, is (are) the author(s) of any

book. One might also make a claim that the author is an algorithm embodied in a

very short computer program which would, given time and resources, generate all

possible variations of 25 orthographic symbols in strings of length 1,312,000.

One could make the Borgesian argument that One Man is the author of

all

books.

For that

matter, the writer Pierre Menard, a quixotic character in Borges' story

"The Don Quixote of Pierre Menard," may as well be credited with

authorship of all the books in the Library.

Certainly there are many, many

books whose first page resembles the one in figure 4. How many such books?

Specifying one page means that 80 symbols for each of 40 lines are

"frozen." This means that out of the 1,312,000 symbols of a book, the

first 3,200 are taken, leaving 1,308,800 spaces to fill. By the work of the

"Combinatorics" chapter, there are thus precisely 25

1,308,800

books with a first page exactly the same as the depicted title page. (Using

logarithms as in the first Math Aftermath, this number is seen to be

approximately 10

1,829,623

books.) Viewed from a complementary angle,

there are 25

3,200

possible first pages, and although significantly

smaller than the numbers we've been contemplating, it is yet another enormous

number. The chance of randomly selecting a book with this particular first page

is "only" 1 in 25

3,200

, approximately 10

4,474

,

which means, essentially, that it will never happen. For comparison's sake, the

chance of a single ticket winning a lottery is better than 1 in 100,000,000 =

10

8

. So finding such a book is equivalent to winning the lottery

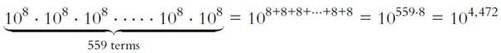

more than 559 times in a row. (In the equation below, each factor of 10

8

signifies winning the lottery once.)

As a source of useful

information for a catalogue entry, a title on the spine of a book, such as

The Plaster Cramp,

is similarly moot, for there must still be something

like

distinct books with the exact

same orthographic symbols on the spine.

Edition,

publisher, city of publication, year of publication—all are meaningless in this

Library. The one sort of information we mentioned that may possibly prove

useful is that of a short description of the contents of the book. We'll take

"short" to mean "half-page or less." It's much more

difficult to say what we mean by "description." We'll take it to mean

"something that significantly narrows the possible contents of the

book." For example, "The book is utter gibberish, completely random

nonsense," doesn't significantly narrow the possible contents of the book.

(We are aware that this definition is problematic.)

Any book

published in the last 500 years likely has a short, reasonably limiting

description. A book whose contents consist of the letters MCV repeated over and

over evidently has a short description. A book whose entire contents are

similar to the 80-symbol line

unmenneo

.ernreiuht.naper,utuytgn or fgioe,no,e,dn .roih senoi.,erg n cprih npp

almost certainly doesn't have

a short description. Or does it? A fascinating area of study in the field of

information theory concerns the difficulty of deciding whether or not a line

such as the one above has some sort of algorithmic description that is shorter

than the line itself. Borges seems to have an intimation of this when he writes

"There is no combination of characters one can make—

dhcmrlchtdj,

for example—that the divine Library has not foreseen and that in one or more of

its secret tongues does not hide a terrible significance." Perhaps

"hr,ns llrteee"

is a more concise description of the line, or

perhaps a succinct translation into English is "Call me Ishmael."

It does no

good to excerpt a passage as a short description; titanic numbers of books in

the Library will contain the same passage. In an important sense, then, for all

languages currently known by human beings, for the cataclysmic majority of

books in the Library,

the only possible description of the book is the book

itself.

This, in turn, leads to a lovely, inescapable, unimagined

conclusion:

The

Library is its own catalogue.

Let's restrict the

investigation to a slightly more agreeable collection of books: all those whose

entire contents cohere and are recognizably in English, and whose first page

contains precisely a short title and a half-page description, both of which

accurately reflect the contents. Any rule of selection will have problems. Some

associated with this one are: What does it mean to "cohere"? Would a

collection of essays on different topics constitute a coherent work? Would

sections of James Joyce's infamous novel

Finnegans Wake

register as

"recognizably English"? What if the book contains a non-English word,

such as "ficciones"? What if the title, as in the case of

Ulysses,

is more allusive than descriptive? Can any description "accurately

reflect" the contents of a book? Regretfully, we'll ignore these and other

legitimate, interesting concerns.

For example,

suppose the first page of a volume of the Library began with the following

description, modified slightly from the back cover of the 2002 Routledge Press

edition of Wittgenstein's

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

Tractatus

Logico-Philosophicus by Ludwig Wittgenstein

Perhaps the

most important work of philosophy written in the twentieth century, Tractatus

Logico-Philosophicus was the only philosophical work that Ludwig Wittgenstein

published during his lifetime. Written in short, carefully numbered paragraphs

of extreme brilliance, it captured the imagination of a generation of

philosophers. For Wittgenstein, logic was something we use to conquer a reality

which is in itself both elusive and unobtainable. He famously summarized the

book in the following words, "What can be said at all can be said clearly,

and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence."

If next came the precise

contents of the book, including Bertrand Russell's introduction, followed by

the appropriate number of pages consisting of nothing but blanks, then that

Library volume would be included in the collection. We are also willing to

include books longer than 410 pages, so long as the title page includes

reference to an appropriate volume number. This allows, among other things, for

the inclusion of this Catalogue of Books in English into the putative catalogue

we are trying to define, which we may as well call

Books in English.