The Up-Down

Authors: Barry Gifford

Tags: #novel, #barry gifford, #sailor and lula, #wild at heart

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

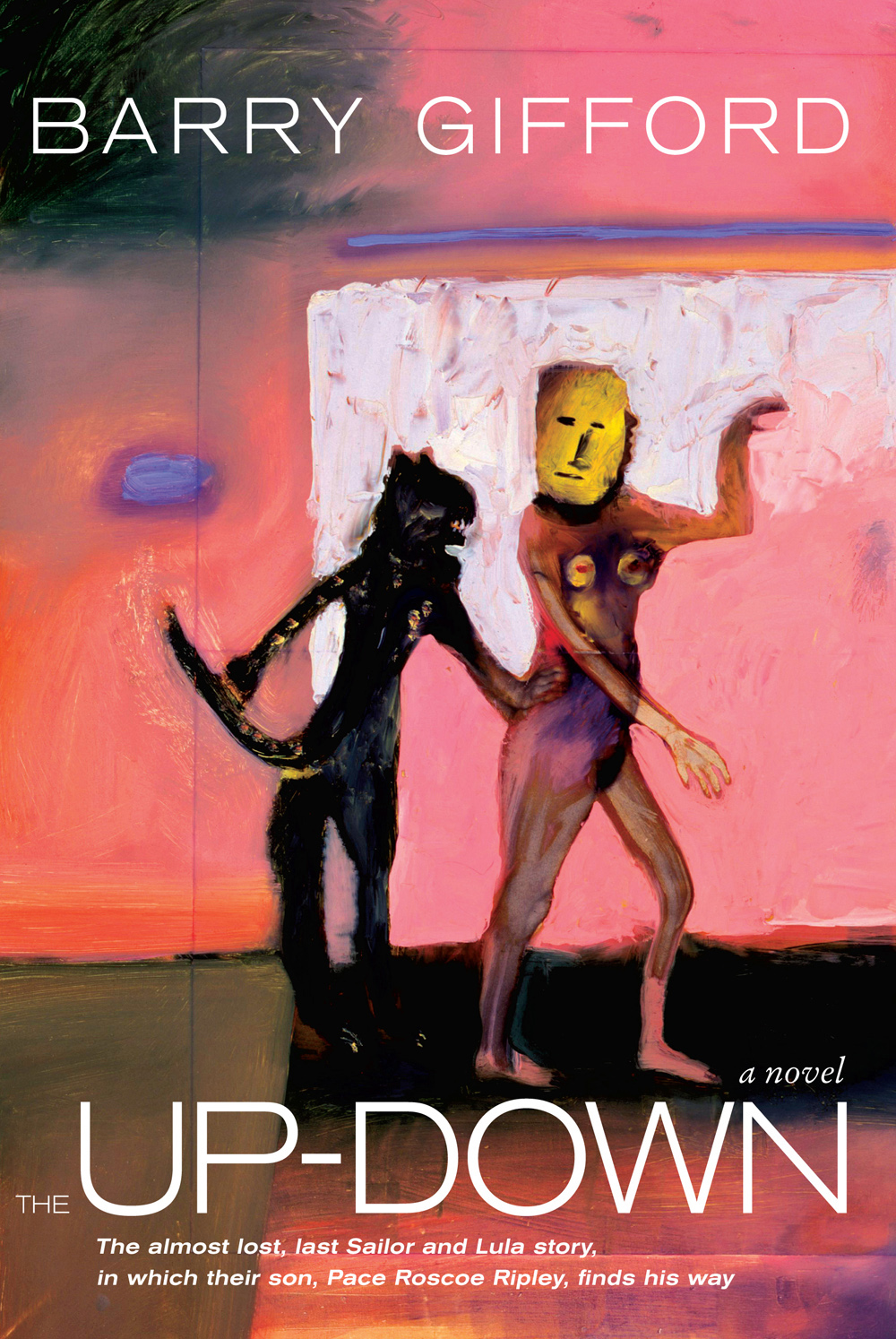

THE

UP-DOWN

The almost lost, last Sailor and Lula story, in which their son, Pace Roscoe Ripley, finds his way

BARRY GIFFORD

Seven Stories Press

New York

Â

This book is for Tita Sorciaâ

“en las estrellas que hay

sobre el firmamento del Veracruz”

Copyright © 2015 by Barry Gifford.

A Seven Stories Press First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Excerpts from

The Up-Down

have appeared in the magazines

Nexos

(Mexico City),

Hotel Amerika

(Chicago),

Vice

(New York), and, in different form,

The Chicagoist

(Chicago).

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

sevenstories.com

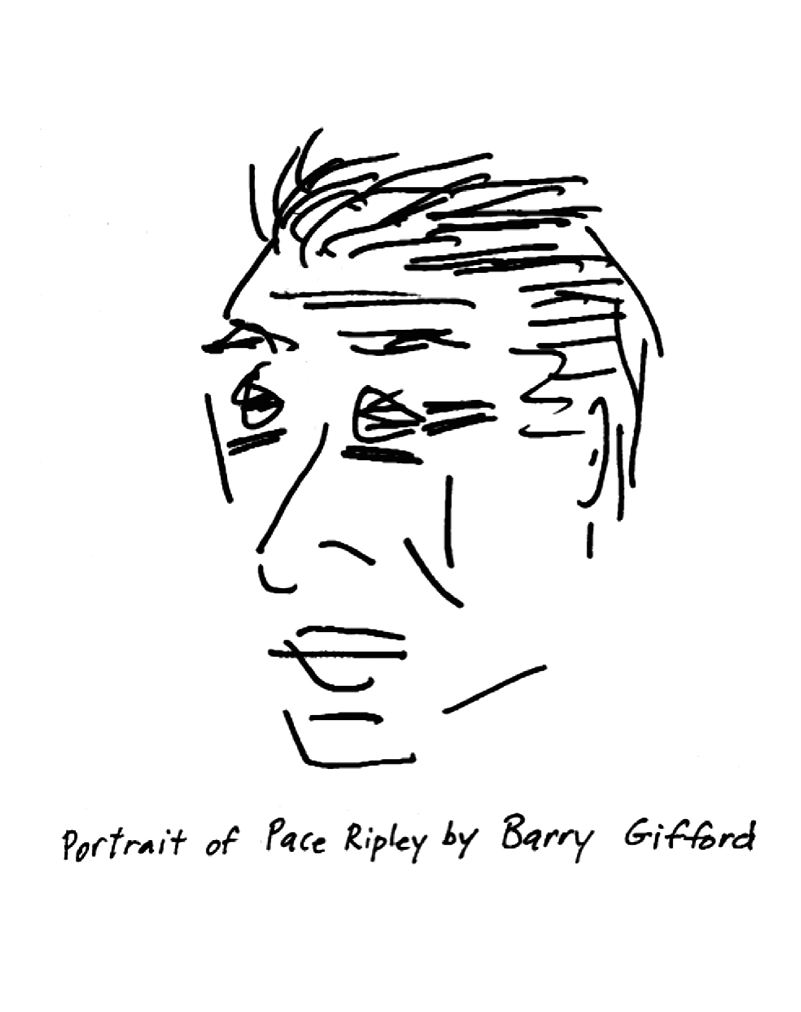

Cover painting “Woman with Mountain Lion” by Holly Roberts, 1985. The drawing of Pace Ripley is by Barry Gifford. The anecdote on page 188 involving Aurelio Audaz and the old Mascogo is credited by the author in part to Guillermo Arriaga and in homage to Jorge Luis Borges.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gifford, Barry, 1946-

The up-down / Barry Gifford. -- First edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-60980-577-7 (hardback)

1. Young men--Fiction. I. Title.

PS3557.I283U73 2015

813'.54--dc23

2014004825

Printed in the USA

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Â

Â

“Death is nothing, nor life either,

for that matter.”

â

Mata Hari

“. . . if I turn mine eyes upon myself,

I find myself a traitor with the rest.”

â

William Shakespeare

Â

Â

Part One

Â

Â

1

Following the death of his mother, Lula Pace Fortune Ripley, Pace Roscoe Ripley, who was at that time living in New Orleans, was seized by a desire to turn his life in a new direction. Pace was fifty-eight years old and he had been engaged in the rebuilding of his home place of N.O. after the devastating damage done to that city due to the flood caused by the failure of the levees occasioned by Hurricane Katrina. Now that both his parents had passed, and with no really significant sentimental attachment to keep him there, Pace resolved to find a solution more personal and closer to his heart. He completed the renovation projects already underway, then dissolved his small construction company, said goodbye to those who had worked with and for him, and, without fanfare, left town.

During the several weeks it took him to complete his affairs in N.O., Pace spent a considerable amount of time deliberating about which direction to go. Years before, he had read that in ancient times various societies, including the Irish, Chinese and Indo-European cultures, believed there were five directions: North, South, East, West and the Up-Down, which represented the navel or center. He had remembered this ever since he'd learned of it, and liked the idea of a fifth, mysterious direction. The center of things is where Pace decided to go. Having lived for periods in places as diverse as New York City and Kathmandu, Nepal, he knew that geography had nothing to do with it, that the signs of the Up-Down pointed inward, that it was time for him to figure out exactly what that meant, and that to get there he had to travel alone.

Â

Â

2

“I once knew a man whose senses were so acute that he could hear a flea dancing on a silk handkerchief.”

Pace studied the face of the man who said this. He had introduced himself as Dr. Boris Furbo, of Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, soon after Pace had sat down next to him on the City of New Orleans, the passenger train running between N.O. and Chicago. Dr. Furbo, who looked to be in his late sixties or early seventies, wore a yellow-and-white-dotted bow tie with a green seersucker suit. He had almost no hair on his head or on his face, including eyebrows, which were mere creases under his forehead. His rimless, blue-tinted eyeglasses were perilously sustained by a nose no larger than the thumb of a seven year old child. He explained to Pace that he was returning to Wisconsin from a conference on hysterogenics, which he defined for Pace as the study of the origins of unsuitable and/or uncontrollable sexual behavior. The doctor claimed that his clinic in Lake Geneva offered the only reliable treatment for this condition, the mandatory textbook being his own

Guide to Furbotics: The Cauterization Theory and Its Uses, Including a Cessation Process Evidenced by the Eradication of Varietal Types of Caterwauling

. Dr. Furbo dug a copy of the book out of a brown boarhide satchel set on the floor between his feet and handed it to Pace.

“Here, my man,” said the doctor. “After you've read it, you'll never think the same way again about Ingrid Munch's Oslo Syndrome.”

Dr. Furbo suddenly stood and picked up his satchel. Pace was surprised at how tall he was, perhaps six foot six or seven. Furbo strode to the far end of the car and went through the connecting door to the next. Pace did not see him again for the remainder of his journey to Chicago, which, excepting this brief encounter with the dubious doctor, was uneventful. As to the book, each page was entirely blank except for the word “Fin” on the very last, which Pace knew was French for The End.

Â

Â

3

Pace had saved some money from his construction projects in New Orleans and he had inherited a small amount from his mother upon her death, as well as Dalceda Delahoussaye's house in Bay St. Clement, North Carolina, in which Lula had been living. Pace had contracted with a realty company in Bay St. Clement to rent the house, so he also had a little income from that. He felt a bit guilty for leaving New Orleans, but following Lula's death for some reason he felt unusually restless, as if the spirits of both his parents were summoning him, calling from the Great or Not-So-Great Beyond, wherever or whatever that might be, to hurl himself off the cliff of Been There into the ocean of What Could Be. Other than his former paramour Marnie Kowalski, with whom Pace had remained on appreciably more than good terms, and Luther Byu-Lee, a musician whose house he had rebuilt in the Lower Nine, Pace figured there wasn't anyone in N.O that he would miss spending time with more than the ordinary. He'd never been one for hanging on the telephone and he didn't e-mail, text or tweet. Pace did like to send postcards, however, so as long as there was still a United States Postal Service he could keep in touch with those few individuals still on the prowl in the active file of his cerebral cortex.

He knew nobody in Chicago and very little about the city except that it got extremely cold in the winter and the powerful wind that blew in off of Lake Michigan was called The Hawk. It was June now, so cold would not be an immediate problem; and even if it got hot and sticky the humidity wouldn't have anything on summer in New Orleans. When he disembarked from the train at Union Station, Pace stood for a few minutes on the platform looking around and thinking about what he should do first. There was no sign of Dr. Furbo.

Pace had a backpack and a roller suitcase. All of his other possessions he'd stored in a shed in the yard behind Marnie Kowalski's house on Orleans Street. He walked to the taxi stand and asked a driver to take him to a not-too expensive but clean small hotel near the Art Institute. Pace had always wanted to see the original of Georges Seurat's painting

La Grande Jatte,

which he knew was on permanent display there. This was one thing he'd long desired to do so it seemed like a good start. On the drive over, Pace hummed softly the tune “In a Small Hotel,” the way he'd so often listened to it played by the tenor saxophonist Stan Getz.

“You ever been in Chicago before?” the driver asked.

“No,” said Pace. “Always wondered about it, though. Heard good things.”

“Well, it's a city like any other, only bigger than most. Some good things, as you say, some bad. Where you from?”

“New Orleans.”

“I had family in Louisiana,” said the driver. “Close by Baton Rouge. They all passed now, though.”

“Did you ever get down there?”

“Yes, sir, a few times when I was a boy, but that was more than forty years ago. Recall catchin' catfish with my cousin Charles, with our hands. Charles showed me how to hold 'em without those sharp spears poke out both sides of their head don't cut you up.”

“That was good of him. Catfish cuts can be plenty nasty.”

“Yes, sir. Poor Charles, though, he only made it to sixteen years old when he got shot bein' in a wrong place at a wrong time, buyin' a RC Cola in a convenience store when some fool tried to rob it. Clerk took up a pistol and kept firin' until all the bullets was used. One of 'em hit Charles in the head. Robber got away.”

“That's a sad story,” said Pace.

“Mm-hmm. I'll take you to a little hotel two blocks from the art museum, the Blackhawk, named after the Indian chief lived around here back in the day. They call it a boo-teek, 'cause of the size, but it's priced very reasonable and decent folks work there. My sister, Marvis, she works on the reception desk. Tell her Arvis brought you by.”

“Arvis and Marvis, huh?”

“Uh huh. Got a brother named Parvis, the oldest. Our mama had a real affection for rhymin'. She told me she'd had a fourth child, she would have named him Jarvis, or if it was a girl, Narvis. Here we are now.”

Pace was checked into the Blackhawk by Marvis, who told him that her brother brought customers to the hotel only if he had a good feeling about them. She gave Pace a room on the fourth floor with windows overlooking the street. Pace lay down on the bed and immediately fell asleep. He dreamt that he was a little boy again and he was riding in the back seat of his father's car. Sailor and Lula were in the front. Sailor was driving as night fell. “Daddy,” Pace said in his dream, “aren't you gonna turn on the headlights?” Lula turned around and smiled at him. Her face was silvery blue in the dusk light. “Don't worry, darlin',” she said, “we don't need them any more.”

Â

Â

Â

4

The first thing Pace did the next day at the Art Institute was look at Seurat's painting. It was much larger than he'd expected it to be and he was pleased to finally be standing in front of it, but he was disappointed that it was covered by glass and at certain angles was difficult to see properly. After he'd had enough of

La Grand Jatte

, Pace toured most of the rest of the museum, then went outside and stood near one of the lion statues at the entrance and watched the traffic crawl by.

He thought about his parents, Sailor and Lula, and how impossible it seemed to him that neither of them was alive. As long as his mother was still on the planet, Pace felt that Sailor, even though he had preceded Lula to the promised land by fifteen years, through her remained near by, his spirit if not his consciousness embodied in Lula. She was forever “consulting” Sailor, as she put it, considering what he would do or say in a certain situation. At least Pace had had a good last visit with his mother when she and her dearest and most enduring friend, Beany Thorn, had driven down from North Carolina to New Orleans to see him. The fact that Beany had been with Lula when she expired consoled Pace some. Anyway, he was almost sixty years old now and he'd led an interesting life, from N.O. to New York, to Nepal, Los Angeles and back to N.O. The problem, Pace had realized for a long time, was that he had been marked so deeply by the mutual devotion of his parents. Their undying love was a kind of miracle, he believed, and the fact that he never found the Big Love he expected to show up made Pace wonder if his own life had been a failure. Perhaps if he and his ex-wife, Rhoda Gombowicz, had had children, he would feel differently. He'd loved Rhoda but their time had run out thirty years ago. She was gone now, too, of course. After they'd divorced and Pace had taken himself off to Kathmandu, Rhoda had gone back to college and become a primate ethnologist. While doing fieldwork in Rwanda, studying gorillas, she was killed by poachers who had in an effort to cover up their crime dismembered her body and buried the parts in different places in the jungle. Only Rhoda's head and her left leg were found and returned by the Rwandan government to her parents.

Pace had read about her death and the circumstances of it by chance in a month-old copy of

The International Herald Tribune

while he was recovering in Bangalore, India, from two broken ankles suffered during a trek in the Himalayas. Rhoda's murder was investigated but the perpetrators had never been found. Harvard University, which had funded her research, apparently mounted a plaque in Rhoda's honor on a wall in their anthropology department but Pace had never gone to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to see it. He had, however, visited Rhoda's grave, which, of course, contained only the remains of her headâone ear was missingâand one leg, in a cemetery at Montauk, Long Island, where her parents, Irving and Greta Gombowicz, had gone to live following Irving's retirement from the New York City Fire Department. Engraved on Rhoda's tombstone, other than her name and dates of birth and death, were the words: “Her Heart Is With The Animals She Loved.”

It was time, Pace decided, while watching a red Toyota Prius being driven by a woman talking on a cell phone rear end a city bus, to get serious about the Up-Down.