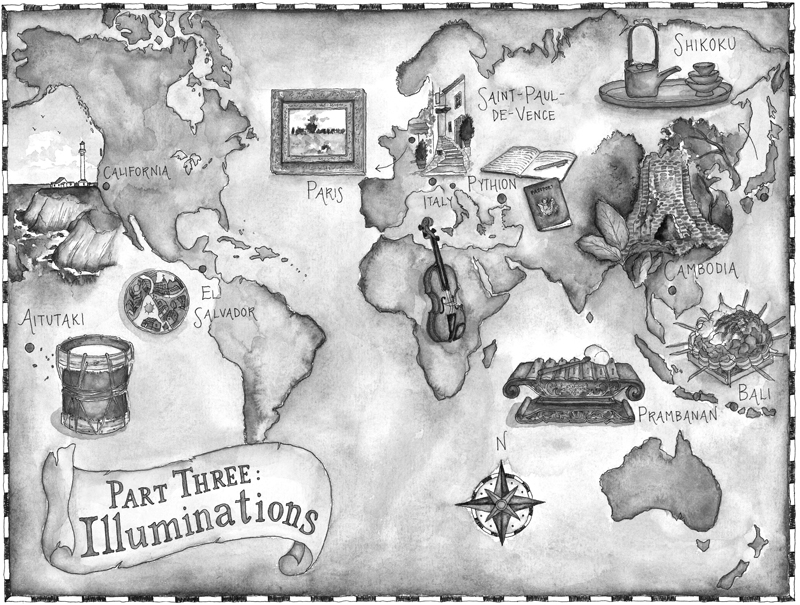

The Way of Wanderlust (28 page)

This story came from a Baltic cruise I took with my wife in the summer of 2014. I wasn't expecting to get any material for great stories on this cruiseâthe trip was supposed to be a vacationâand this piece is a good example of why a travel writer should always have his/her mind open and alert. Before we docked in Germany, I had arranged for a private half-day tour of Berlin with a guide. As we approached the capital on the train from the port, I imagined we would have a pleasant four hours seeing the city's main sights and monuments. But as soon as we met our guide and she began talking in a deeply personal way about the day the Berlin Wall came down, everything changed. Goosebumps rose all along my skin as she told her impassioned tale, and we felt transported through time with her. Sometimes the world delivers the deepest connections when we least expect itâand that's why we have to be alive to every moment.

![]()

IT'S ONE THING TO STAND IN A PLACE

where a historic event transpired a thousand years ago. It's entirely different to stand in a spot where history was made during your own lifetime.

This lesson resonated for me on a mind-expanding cruise around the Baltic Sea in the summer of 2014. Our voyage included day tours in Stockholm, Tallinn, Helsinki, St. Petersburg, and Copenhagen. In each city we gazed at grand, centuries-old cathedrals and statues commemorating epoch-making events. And yet in each, history remained somehow cerebral and out of reachâuntil we reached Berlin.

My wife and I traveled by train from the port of Rostock to Berlin's central rail terminal, where we met a wonderful guide, Sabine Mueller, who immediately took us to the Brandenburg Gate.

As we stood in the shadow of the iconic arch, Sabine said, “I want to tell you about the night the Berlin Wall came down.”

She recalled that in a news broadcast aired at 8:00

p.m

. on November 9, 1989, the East German authorities announced that the eastern borders, including the borders between East and West Berlin, would be opened. She was twenty years old at the time and had been living in West Berlin since she was a toddler.

“People in East Germany listened to these broadcasts, too, and as soon as they heard this news, they streamed to the borders,” she said. “The East Berliners were afraid that the decision might be reversed at any moment and wanted to take advantage of it while they could.

“The next morning I was awakened at dawn by a phone call from my friend. âWe have to go to the Wall!' he said. âWhy?' I asked, still half asleep. âBecause they're tearing it down!'”

Sabine paused and goosebumps ran along my body. I was in two places simultaneously, one foot in modern-day Berlin and the other in the newsroom at theÂ

San Francisco Examiner

that long-ago November day as the first reports streamed over the wire. Standing in Berlin in 2014, I felt the same exhilarating breeze I'd felt in 1989 as I read eyewitness accounts from the German capital and marveled that changes beyond my comprehension were sweeping across the planet.

Sabine pointed at our feet, where a trim line of light gray concrete perhaps eight inches wide ran down the street. “This marks where the Berlin Wall stood,” she said. “My city was divided.”

“Think of it,” she continued. “Twenty-eight years earlier, in 1961, barbed wire had been erected overnight. Some East Berliners who had spent the night in West Berlin woke up unable to return home, or faced the decision of whether to stay in the free West or return to loved ones in the East, knowingly giving up their chance for freedom. Some people who lived in East Berlin but worked in West Berlin suddenly couldn't go to their jobs. Families and friends who lived on separate sides of the Wall were torn apart.”

Sabine explained with photographs that the Berlin Wall was actually two walls separated by a no-man's-land that varied in width from about 30 to 500 feet and was punctuated at regular intervals by watchtowers and guards. Anyone attempting to cross was shot, she said.

“So you can imagine the euphoria I felt, we all felt the next morning when my friend and I raced to the Wall,” she went on. “There were crowds of people drinking and dancing and celebrating. Some people had hopped on top of the Wall; others were chipping away parts of it. No one knew what the future would bring, but in that moment no one was thinking of the futureâwe were just intoxicated by the sense of history happening under our feet, in front of our eyes.”

Three hours later, Sabine ended our tour at one of the most substantial sections of the Wall still standing. Alone, isolated, stretching about a city block, it seemed such a frail confectionâa long drab wafer of a wall, perhaps ten feet tall and less than a foot thick, that looked as though it could be toppled with a good kick.

I stared and thought of all the lives that Wall had ripped apart, the dreams that it had buried. It was almost impossible to grasp the authority it had once imposed. Indeed, Sabine said her own school-age children found it hard to believe the Wall had ever existed. It seemed so absurd, so impossible.

It was an equal challenge to reconcile the privations of the Communist past with the prosperity of the capitalist present, proclaimed in the bold, corporate-branded buildings and brisk, besuited businessmen we'd seen on our tour. And that was a good lesson, tooâthat Berlin was resolutely not mired in its past, but had moved on to embrace a once inconceivable future.

As we surveyed that symbolic slice of concrete, Sabine smiled broadly, her eyes alight, and I thought anew of how travel can connect us to historyâand to the people and stories that compose itâin the most visceral, heart-pounding way.

I thought, too, of another truth, fundamentally related to travel but soaring beyond it: that no wall can subdue forever the human will.

And as I imagined Sabine dancing and hugging her newly freed countrymen in this very spot in the fall of 1989, these words formed in my mind: Walls fall; people rise.

Berlin's living history had opened my eyes.

![]()

I visited the Musée d'Orsay in Paris on the same momentous return trip where I had the epiphany in Notre-Dame Cathedral which I wrote about earlier in this collection. Both of those pieces were the product of a lesson that was just beginning to crystallize for me: the importance of focus. The closer you focus on a place or a thing, the more you notice, and the more you have to say. When I began this essay, I wanted to write about the extraordinary richness of art in Paris, and how that richness added layers to the life of the city and to my interaction with that life. I first tried to write about three museums, but in my 750-word

Examiner

column, I could barely begin to say anything about each museum. Then I tried one museum, then one gallery in one museum, then five paintings in that gallery. Each time, the essay seemed too superficial, just glancing the surface of the topic. Finally I realized that the only way to do this topic justice would be to focus deeply on one painting and re-create my interaction with that painting. And that's what I tried to do in this essay. After it was published, an art professor at San Francisco State University wrote to me that she was making it required reading in all of her coursesâso perhaps I did something right!

![]()

I HAVE BEEN LOOKING AT MONET'S

Les Coquelicots

, the painting of two women and children walking through a field of bright red poppies on a sunny, cloud-dappled day, for about forty minutes. It moves me just as profoundly now as it did when I was last in Paris twelve years before; it still tugs deep within me, cuts through all the layers to something fresh and fundamental and childlike.

At first I stared at it closely, my nose within a foot of the canvas, so close that I could see the black-dot eyes of the child in the foregroundâsomething I had never seen before, or at least never remembered seeing.

Get that close and you reduce the painting to its elements: layers of oil paint on canvas, brushstrokes, dabs, tiny tip-tips with the brush. You realize just how fragile a thing a painting is, and just how common.

And you realize too that it was made by a manâfragile, commonâwho stood at the canvas and thought: “a little more red here,” dab, dab; “a cloud there,” push, push; “how can I capture that light?”

Look at the painting closely this way for a few minutes and you break it down into an intricate complexity of colors and textures and forms.

Then step back andâ

voilÃ

!

â

all of a sudden it is a composed whole, a painting: a cloud-bright sky and poppy-bright field, a woman with a fancy hat and a parasol and a child almost hidden by the tall grasses in the foreground, and in the background another woman and a child almost obscured against a distant stand of trees. They are on a walk, or a picnicâa story begins to compose itself, to take on a life inside and outside the canvas.

And you realize that this is a kind of miracle, that colors and shapes dabbed on a piece of cloth 115 years ago have somehow reached across time and culture to touch you.

Look long enough and feel deeply enough, and your eyes fill with tears.