The Way of Wanderlust (3 page)

Every Journey Is a Pilgrimage

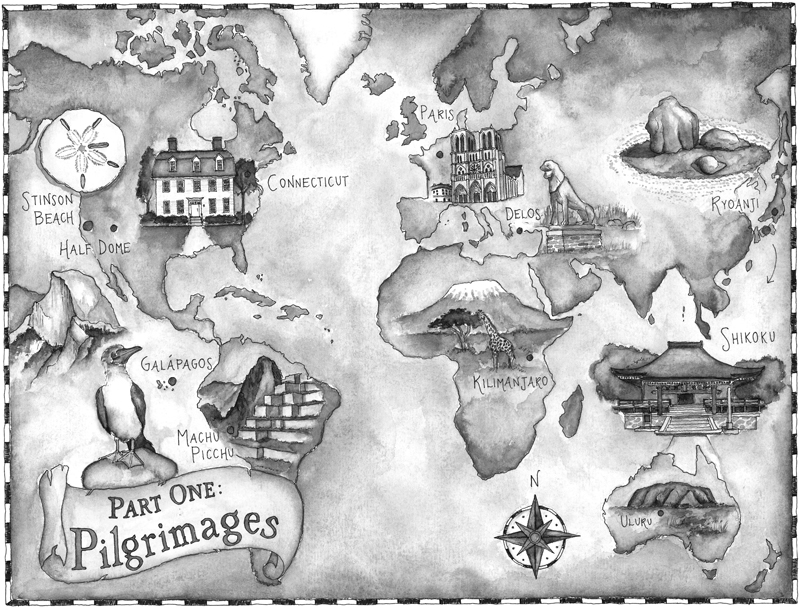

When an editor with whom I had worked at Salon moved to

Yoga Journal

, she asked me if I would like to write an essay about my philosophy of travel, what travel had taught me through the years. This essay, written in early 2004, was the first piece where I succinctly expressed two ideas that had been germinating for decades and that have become the very foundation of my philosophy now: Travel is a way to collect pieces of the vast global puzzle so that we can understand that puzzle better, and travel is an act of pilgrimage that sanctifies the world, wherever and whatever the path we walk. In retrospect, I believe this all happened exactly as it should: It took a journal devoted to yoga, shining its light on me at a particular moment in my own journey, to ripen these seeds to full fruition.

![]()

ONE OF THE MOST REWARDING TRIPS OF MY LIFE

was a five-day solo odyssey I made a few summers ago around the Japanese island of Shikoku. Shikoku has been a place of pilgrimage since the 9th century, when the beloved scholar and monk Kobo Daishi established a path of eighty-eight Buddhist temples that circle the island. Completing this circuit is supposed to give you great wisdom, purity, and peace, but I was on a pilgrimage of another kind. My wife grew up on this island, and I had first visited it with her some twenty years before. Now I had returned to see if the singular beauty, serenity, and slow pace of the place I rememberedâand the country kindness of its residentsâhad survived.

A few hours into my journey, I stopped a wizened woman, clad in the pilgrim's traditional white garb and cone-shaped straw hat, scuffling along a leaf-paved path. She was on her second temple circuit, she told me. “The thing about the pilgrimage,” she said, “is that it makes your heart lighter; it energizes you. It refreshes your sense of the meaning of life.” Then her eyes locked into mine, deep and shining as a cloudless sky.

During my five days on Shikoku, I ate fresh-from-the-sea sashimi with fishermen, philosophized in steaming public baths with farmers, spun bowls with fifth-generation potters, and talked baseball and benevolence with Buddhist monks. I lay down in rice paddies, lost myself in ancient forests, stared at the sun-spangled sea, and listenedâwith the help of an eighty-year-old “translator” I had met as she was mending a fishing net on a pierâto the whispers of ghosts in the trees. By the end of my odyssey, I too felt lighter, refreshed, and energized, but not because of the sanctified sites. The island itself had become one big temple for me.

That trip confirmed a truth I had sensed during two decades of wandering: You don't have to travel to Jerusalem, Mecca, Santiago de Compostela, or any other explicitly holy site to be a pilgrim. If you travel with reverence and wonder, with a lively sense of the potential and preciousness of every moment and every encounter, then wherever you go, you walk the pilgrim's path.

I began to learn this after I graduated from college and moved to Athens, Greece, to teach for a year. By the end of that year, the wonders of the world had ensnared me. I would sit for hours on the Acropolis, staring at the bone-white Parthenon, trying to absorb the perspective of the ancients. I consulted the crimson poppies and fluted marble fragments at Delphi. I meditated on Minoan marvelsâbull dancers, mosaic makersâamong the tangerine-colored columns of Knossos on Crete. I drank ouzo with fellow teachers and excavated the hidden truths of Aristotle and Kazantzakis on a sun-spattered terrace overlooking the Aegean. I danced with wild-haired women under bouzouki-serenaded stars. I fell in love with the world.

In his seminal essay, “Why We Travel,” Pico Iyer writes, “All good trips are, like love, about being carried out of yourself and deposited in the midst of terror and wonder.” Travel stretches us so that our mental clothes don't fit anymore; it reminds us over and over that the anchoring assumptions of our youth lose their hold in the global sea. Travel to strange places can make us strangers to ourselves, but it can also introduce us to all the exhilarating possibilities of a new self in a new world.

Inspired by my experience in Greece, I applied for a two-year fellowship to teach in a place that was far more foreign to me than anywhere I'd been before: Japan. I knew nothing of Japan's customs, history, or language, but something was pulling me there. Trusting and terrified, I won the fellowship and took the plunge.

It was while I was living in Tokyo that the first great lesson of travel revealed itself to me: The more you offer yourself to the world, the more the world offers itself to you.

This revelation began with my getting lost. I have an uncanny ability to become lost in even the most obvious circumstances, and in Japan, this predisposition was heightened by my inability to read Japanese. Because I was always losing my way, I had to learn to rely on people. And they came through: Time after time, Japanese students, housewives, and businessmen would walk or drive fifteen or even twenty minutes out of their way to deliver me to the proper train platform, bus stop, or neighborhood. Sometimes they would even press little wrapped red-bean sweets or packets of tissues into my hands when they said goodbye.

Buoyed by these kindnesses, I traveled to Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia for the summer. Once again, I knew no one and couldn't speak the language; I was at the mercy of the road. But I was beginning to trust. And as it turned out, everywhere I went, the more I opened myself up to people and relied on them, the more warmly and deeply they embraced and aided me: A family at an open-air restaurant in Kuala Lumpur noticed me smiling at their birthday celebration and invited me to join the feast; two boys in Bali pedaled me to a secret temple set among glistening rice paddies.

Looking back, I realize that I was refining my practice of vulnerability, a practice as rigorous and soul-scouring as any contemplative art. Becoming vulnerable requires concentration, devotion, and a leap of faithâthe ability to abandon yourself to a forbiddingly foreign place and say, in effect, “Here I am; do with me what you will.” It's the first step on the pilgrim's path.

The second step is absorbing a lesson that grows from the first: The more you humble yourself, the greater you become. I have felt this in Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, imagining the ceaseless processions of worshippers who had come before me and would come after. I have felt it in the main train station in Calcutta, adrift in a sweaty, sharp-elbowed, eternally jostling, cardamom-scented sea of humanity. I have felt it walking alone on the Karakoram Highway in Pakistan, between towering peaks so ancient and enormous that I felt smaller than the tiniest grain of sand. Travel teaches us how small we areâand when we truly understand this, the world expands infinitely. In that moment, we become part of the larger whole; we lose ourselves to the Parisian stone, the Indian crowd, the Himalayan crags.

This truth has led me over the years to a third illumination: Every journey takes us inward as well as outward. As we move through new places, encountering new people and food and artistic creations, new languages and customs and histories, a corresponding journey winds within as we discover new morals, meanings, and imaginings. The real journey is the ongoing and ever-changing interaction of the inner life and the outer.

When we travel, we connect the external world with the one inside. On the best trips, these connections can become so complete that a kind of larger

union is achieved: We transcend not just the barriers of language, custom, geography, and age but the very barriers of self, those illusory isolations of body and mind.

These moments do not last. We exit Notre-Dame, buy our ticket in Calcutta, climb back into our minivan in the Himalayas. But we come back from those momentsâlike the Japanese pilgrim I metâlighter and energized, with a refreshed sense of the meaning of life.

What I relearned on my circuit of Shikoku is that every journey is a pilgrimage. Every sojourn offers the chance to connect with a sacred secret: that we are all precious pieces of a vast and interconnected puzzle, and that every trip we take, every connection we make, helps complete that puzzleâand ourselves.

Thinking of this now, I realize that the goal of all of my life's journeys has been to connect as many piecesâas many places, as many peopleâas possible, so that at some point, I could complete that picture puzzle within myself.

This completion hasn't happened yetâbut what rewards I am finding along the way! Travel has taught me to see beyond barriers. It has taught me to abandon myself to a sashimi celebration in Japan and the spine-tingling hush of Notre-Dame, to the gift of two bicyclists on Bali and the soul-plucking Hellenic stars. I may not know what I will encounter, endure, experience, or explore on my next journey, but I know that it will enrich and enlarge me, and illuminate a little more of the whole.

“Climbing Kilimanjaro” was my first travel story, published in November 1977. I had climbed the mountain on a summer trip to East Africa between Greece and creative writing graduate school in the U.S., and I wrote this story as an assignment in a non-fiction writing workshop. Perhaps because I wasn't a travel writer and didn't really have any idea what travel writing was or was supposed to be, I wrote this more as a short story-meets-essay, with substantial doses of both dialogue and personal reflection. And perhaps that's why it stood out for the

Mademoiselle

Travel Editor. Thirty-eight years later, I'm still astoundedâand gratefulâthat my first attempt at a travel story, written as a workshop assignment and handed to an editor as a writing sample, would become my first published article in a national magazine, and just a few months after I wrote it. This was a very encouraging beginning to my travel writing career!

![]()

THREE GREEKS AND TWO AMERICANS DRAG

five army-green duffle bags from a glaring white Range Rover into equatorial noon, hoist bags onto cotton workshirts already soaked with sweat, and trudge along a dirt path, up eight rock steps to a polished log cabin titled in teakâKilimanjaro Climbers' Registration Office.