The White Goddess (57 page)

Authors: Robert Graves

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Mythology, #Literature, #20th Century, #Britain, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Mysticism, #Retail

But is not the answer to our question to be found in

The

Battle

of

the

Trees?

What distinguishes the BLFSN from the BLNFS is that the letter N,

Nion

the ash, the sacred tree of the God Gwydion, has been taken out of the dead period of the year, where it is still in black bud, and put two months ahead to where it is in leaf, while

Fearn

the alder, the sacred tree of the God Bran, which marks the emergence of the solar year from the tutelage of Night, has been thrust back into

Nion

’s place. The BLFSN is the trophy raised by Gwydion over Bran. And is it not strange that a few years before the Battle of the Trees was fought in Britain and the letter F humbled, the Greeks had made a dead set against their F, only retaining it as a numerical sign for 6? More than this happened when the order of letters changed; Gwydion’s ash, N, took the place of the fifth consonant,

Saille

the willow, S, which was naturally sacred to Mercury, or Arawn; and Gwydion thereupon became an oracular god. Also, Amathaon who had evidently been a willow-god, S, took Bran’s place at F and became a fire-god in the service of his father Beli, God of Light. It only remained in this General Post for Bran to take over the maritime ash that Gwydion had relinquished and sail away on his famous voyage to one hundred and fifty islands; yet sailing was no novelty to him, the tradition preserved by Virgil being that the first boats that ever took to the water were alder-trunks.

1

In Crete today a pre-marital love-affair has only two possible results: a knife between the lover’s shoulders, or immediate marriage. The German Panzer Grenadiers stationed in Crete during World War II had to go on leave to Mount Athos if they wanted sexual diversion.

1

And probably with female breasts, as in a Middle Minoan seal-type from Zakro, published in Sir Arthur Evans’

Palace

of

Minos.

1

It seems to have been in her honour as Goddess of the dark-blue night sky and the dark-blue sea that the matrons and girls of Britain, according to Pliny, stained themselves all over with woad, for ‘certain rites’, until they were as swarthy as Ethiopians, then went about naked. An incident in the mediaeval

Life

of

St.

Ciaran

proves that in Ireland woad-dying was a female mystery which no male was allowed to witness. If this was also the rule in Thrace and the Northern Aegean, it would account for the nasty stench which, according to Apollodorus, clung to the Lemnian women, and made the men quit their company; for the extraction and use of the dye is such a smelly business that the woad-dying families of Lincolnshire have always been obliged to inter-marry.

Chapter Fourteen

The omission from O’Flaherty’s and O’Sullivan’s Beth-Luis-Nion of the mythically important trees,

Quert

,

apple, and

Straif,

blackthorn, must be accounted for. The explanation seems to be that though the Beth-Luis-Nion calendar is a solar one, in so far as it expresses a year’s course of the sun, it is ruled by the White Moon-goddess whose sacred number is thirteen in so far as her courses coincide with the solar year, but fifteen in so far as the full moon falls on the fifteenth day of each lunation. Fifteen is also the multiple of three and five: three expressing the three phases of the moon and the Goddess’s three aspects of maiden, nymph and hag, and five expressing the five stations of her year: Birth, Initiation, Consummation, Repose and Death. Thus because fifteen letters are needed to present the Goddess as both a triad and a pentad, and to express the days in a month up to full moon, and since only thirteen 28-day months can be fitted into a year, two of the months must be shared between pairs of trees.

Since Q was sometimes written CC by the Irish ollaves – as in O’Flaherty’s alphabet – we may conclude that Z was similarly written SS, as it was in Latin during the greater part of the Republic. This is to say that

Quert

the wild apple shared a month with

Coll

the hazel, because the apple and nut harvest coincide, and that Straif the blackthorn shared a month with

Saille

the willow, because the White Goddess has to make an appearance in tree form in the Spring – in France the blackthorn is called

La

Mère

du

Bois

(‘the Mother of the Wood’).

The blackthorn (

bellicum

in Latin) is an unlucky tree; villagers in Galmpton and Dittisham, South Devon, still fear ‘the black rod’ carried as a walking stick by local witches, which has the effect of causing miscarriages. When Major Weir, the Covenanter and self-confessed witch, was burned at Edinburgh in April 1670, a blackthorn staff was burned with him as the chief instrument of his sorceries. Blackthorn is also the traditional timber with which bellicose Irish tinkers fight at fairs (though the

shillelagh

,

contrary to popular belief, is an oak club), and the words ‘strife’

and ‘strive’, modelled on the old Northern French

estrif

and

estriver

,

may be the same word

Straif

,

derived from the Breton; at least, no other plausible derivation has been suggested. Gilbert White remarks in his

Selborne

: ‘Blackthorn usually blossoms when cold N.E. winds blow; so that the harsh rugged weather obtaining at this season is called by the country people “blackthorn winter”.’ The blackthorn is also called the sloe, after its fruit; and the words ‘sloe’ and ‘slay’ are closely connected in early English. Since Good Friday falls in this month, the Crown of Thorns was sometimes said to have been made of blackthorn; and this was the explanation that the monks gave for the unluckiness of the tree. It is said that whitethorn, tree of chastity, will destroy any blackthorn growing near by.

That

Coll

and

Quert

share a month between them is appropriate. The hazel is the poet’s tree, and the apple’s power as the salvation of poets is brought out in the Welsh legend of Sion Kent (a verse of whose I quote in Chapter Nine) whom the Prince of the Air tried to carry off: Kent won permission to ‘sip an apple’ first, then caught hold of the apple tree, a sanctuary from which he could not be removed. Therefore ‘being too sinful for Heaven yet safe from Hell he haunts the earth like a will o’ the wisp’. In other words, he secured poetic immortality.

Quert

and

Coll

are also associated in the

Dinnoschencas

with the oak, the King of Trees: the Great Tree of Mugna contained in itself the virtues of apple, hazel and oak, ‘bearing every year one crop each of goodly apples, blood-red nuts and ridgy acorns: its crown was as broad as the whole plain, its girth thirty cubits, its height three hundred cubits.’ It fell with the advent of Christianity.

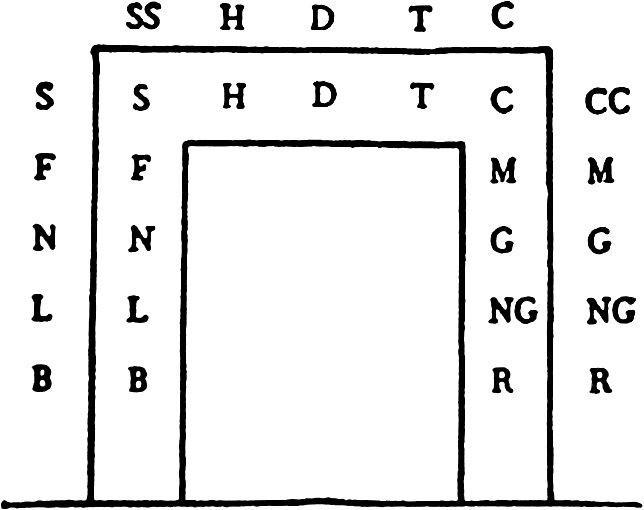

There is a reference in Amergin’s song to the ‘secrets of the unhewn dolmen’. It will be seen that there is room for an extra letter at each corner of the dolmen arch which I constructed to elucidate the reference: the Oghams being nicked on the edges, not painted on the face, of the stones.

It will be observed that the seventh to eleventh letters of this alphabet, which follow the same sequence in the Boibel-Loth, are the letters H.D.T.C.Q. These letters, as Sir John Rhys has pointed out, form the

initials of the Old Goidelic numerals, from one to five:

a

hoina

,

a

duou,

a

ttri,

a

ccetuor,

a

qquenque,

which correspond very nearly to the Latin mumerals

unum,

duo,

tres,

quattuor,

quinque.

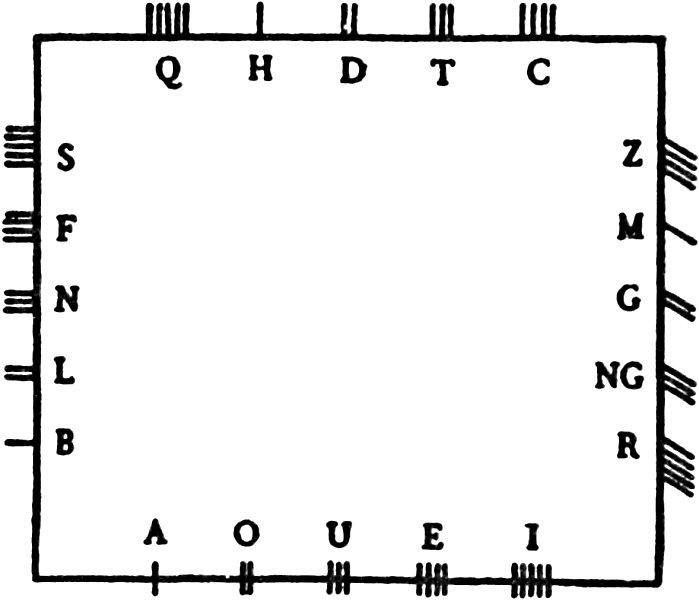

This may explain why the inventors of the Boibel-Loth made H.D.T.C.Q. the central five letters of the alphabet and transferred Z to a position between NG and R. Yet the ancientness of the Old Goidelic numerals suggests that in the original Beth-Luis-Nion finger alphabet the first flight of consonants – the Spring months – numbered only five, not six, to allow H.D.T.C.Q. to form the second or Summer series, and that Z was therefore reckoned to the last series, the Winter series, as a premonitory ‘blackthorn winter’. Thus:

Each series thus has its full five letters, the aggregate number of strokes in each case being fifteen.

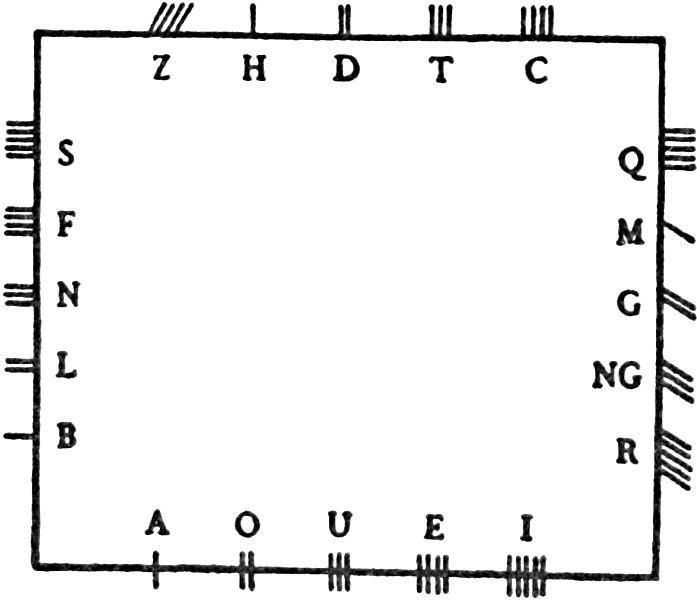

But though this is a logical arrangement, necessitated by the initials of the first five numerals in Latin and Old Goidelic, a sense of mathematical proportion demands that each side of the dolmen should have a single series cut upon it. This would involve a change of places between Z and Q, to make Apple and Willow, Hazel and Blackthorn, share months:

This arrangement makes good seasonal sense, for the wild apple blossoms during the willow month and the sloe is ripe in the hazel month. Poetically it also makes good sense, for the Apple White Goddess is of happier omen than the Blackthorn White Goddess as introducing the summer; and the hostile blackthorn with its mouth-puckering sloe is complementary to the apple, in the nut-month, as representing the poet in his satiric capacity. I believe that both these arrangements were used in Ogham, the necessary ambivalence of poetic meaning being thus maintained: it is an axiom that the White Goddess is both lovely and cruel, ugly and kind.

Now it will be noticed that there are two more unoccupied corner positions on the threshold of the dolmen which represents the extra day of the calendar year; and these can be assigned to J (pronounced Y) and to long O: Y as a reduplication of I, the death-vowel; long O as a reduplication of A, the birth-vowel. That only a single character served for both J and I in Latin and Greek is well known; and the close connexion between long O (Omega) and A appears both in Ionic Greek, where Omega was often written instead of Alpha –

õristos

for

aristos

(‘best’); and in Doric Greek where Alpha was often written for Omega – as

prãtistos

for

prõtistos

(‘first’).

Omega (‘Great O’) seems to signify the world-egg of the Orphic mysteries which was split open by the Demiurge to make the universe: for the majuscular Greek character for Omega represents the world-egg laid on the anvil and the minuscular character shows it already split in halves. The majuscular Omicron (‘little O’) and the minuscular Omicron both show the egg of the year waiting to hatch out. The

glain,

or ‘red egg of the sea serpent’, which figured in the Druidical mysteries may be identified with the Orphic world-egg: for the creation of the world, according to the Orphics, resulted from the sexual act performed between the Great Goddess and the World-Snake Ophion. The Great Goddess herself took the form of a snake and coupled with Ophion; and the coupling of snakes in archaic Greece was consequently a forbidden sight – the man who witnessed it was struck with the ‘female disease’: he had to live like a woman for seven years, which was the same punishment as was permanently inflicted on the Scythians who sacked the Temple of the Great Goddess of Askalon. The

caduceus

of Hermes, his wand of office while conducting souls to Hell, was in the form of coupling snakes. The Goddess then laid the world-egg, which contained infinite potentiality but which was nothing in itself until it was split open by the Demiurge.