The White Goddess (58 page)

Authors: Robert Graves

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Mythology, #Literature, #20th Century, #Britain, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Mysticism, #Retail

The Demiurge was Helios, the Sun, with whom the Orphics identified their God Apollo – which was natural, because the Sun does hatch snakes’ eggs – and the hatching-out of the world was celebrated each year at the Spring festival of the Sun, to which the vowel Omicron is assigned in the alphabet. Since the cock was the Orphic bird of resurrection, sacred to Apollo’s son Aesculapius the healer, hens’ eggs took the place of snakes’ in

the later Druidic mysteries and were coloured scarlet in the Sun’s honour; and became Easter eggs.

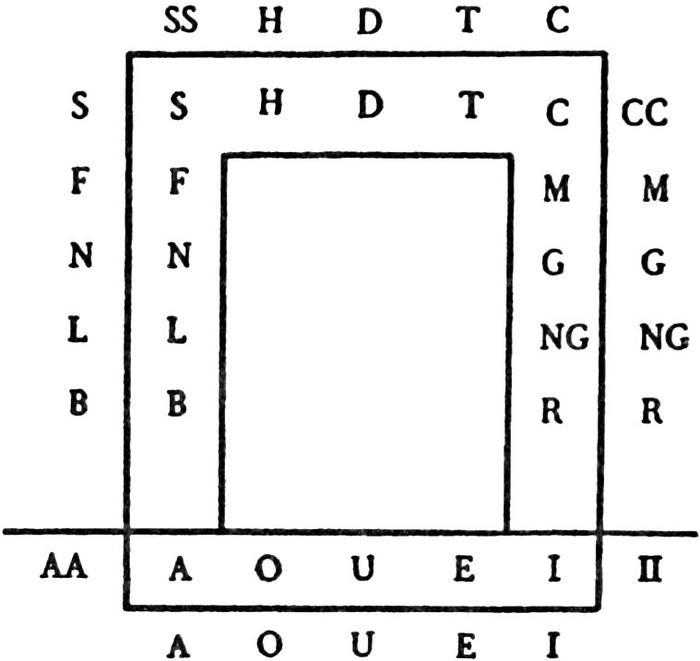

But Little O is not Great O. Great O, Omega, must be regarded as an intensification of Alpha, and as symbolizing the birth of birth. Here then is the new dolmen figure:

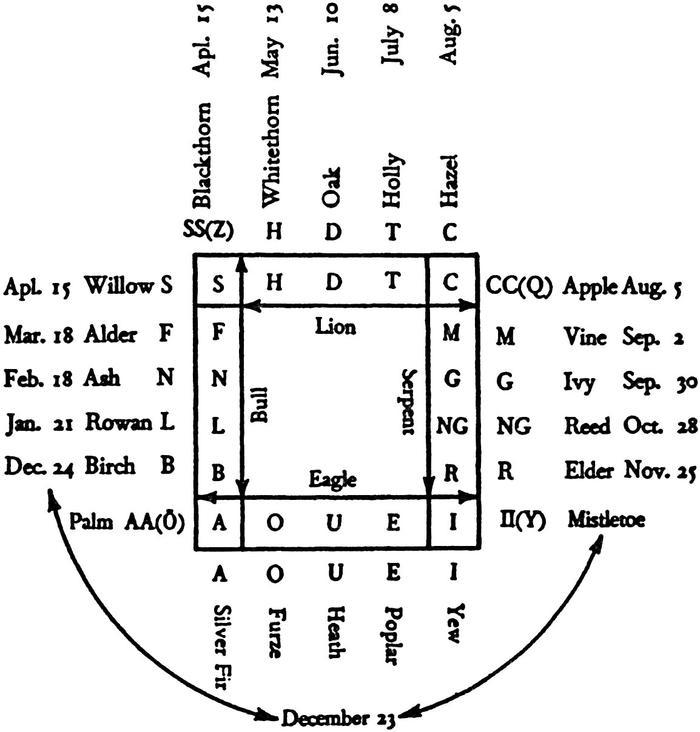

And at last we can complete our Beth-Luis-Nion calendar, with the proper tree accredited to each letter – for the doubled I, or J, letter-tree, the tree belonging to the Day of Liberation which stands apart from the 364 days of the thirteen months, is soon found. Put the requirements of the tree into a bardic riddle and there can be only one answer:

The

lay

that

is

no

lay

calls

for

a

treeThat

is

no

tree,

of

low

yet

lofty

growth.When

the

pale

queen

of

Autumn

casts

her

leavesMy

leaves

are

freshly

tufted

on

her

boughs.When

the

wild

apple

drops

her

goodly

fruitMy

all-heal

fruit

hangs

ripening

on

her

boughs.Look,

the

twin

temple-posts

of

green

and

gold,The

overshadowing

lintel

stone

of

white.For

here

with

white

and

green

and

gold

I

shine

–Graft

me

upon

the

King

when

his

sap

risesThat

I

may

bloom

with

him

at

the

year’s

prime,That

I

may

blind

him

in

his

hour

of

joy.

For the mistletoe, the berries of which were formerly prized both as an allheal and as an aphrodisiac, is not a tree in the sense that it grows in the earth; it subsists on other trees. There are two sorts of mistletoe, the mistletoe proper and the loranthus. The Greeks distinguished them as, respectively,

hypear

and

ixos

or

ixias.

The loranthus is found in Eastern

Europe, but not in Western and, unlike mistletoe proper, grows on oaks. It also grows on tamarisks, and its flame-coloured leaves may have been the original ‘burning bush’ from which Jehovah appeared to Moses. Whether the loranthus was once native to Western Europe, or whether the Celtic Druids brought it with them from the Danube area where their religion was first formulated, or whether they grafted mistletoe proper from poplar, apple, or other host-trees, on their oaks, cannot be determined. It is most likely that they grafted it, to judge from the insistence in Norse myth on oak-mistletoe. Virgil notes that the mistletoe is the only tree that leafs freshly in wintry weather. Its colours are white, green and gold like the pillars and lintel shown to Herodotus in the ancient temple of Hercules at Tyre. On midsummer day, in ancient Europe, the Eye of the year was blinded with a mistletoe stake, all the other trees (according to the Norse legend) having refused to do so. The Church now admits holly and ivy as reputable church decorations at Christmas, but forbids the mistletoe as pagan. However, mistletoe cannot be ousted from its sovereignty of Midwinter, and the exchange of kisses forbidden at all other seasons is still permitted under its bough, if it has berries on it. Chemists have tried to learn how mistletoe won the name ‘all-heal’, by analyzing its alkaloids. They can find none of any curative virtue, though this is not final proof of the mistletoe’s medicinal valuelessness. Camomile, for example, has medicinal properties, but no extractable alkaloid. A plant is rarely awarded mystic virtue unless it has some property beneficial to man. Yet the spectacle of green leaves and white berries on an otherwise bare tree may have been sufficiently odd to invest mistletoe with supernatural powers. The wood, by the way, is extremely hard and tough, mistletoe being slow-growing; Haedur’s mistletoe spear which pierced Balder’s gentle breast in the legend was no poetic fancy – I once cut one for myself in Brittany.

This calendar explains the reference in Gwion’s

Preiddeu

Annwm

to the ‘ox with seven-score knobs on his collar’: the ox is the first flight of five months, consisting of 140 days; it is presumably followed by a lion of one hundred and twelve days, and a serpent of the same length, to justify the two texts already quoted (in Chapter Eight) from Euripides and the Welsh poet Cynddelw – both appealing to the God of the year to appear as a wild bull, a fire-breathing lion and a many-headed snake. The griffon-eagle must be the creature of the extra day, since the god becomes immortal in this form. This year of Bull, Lion, Serpent and Eagle is Babylonian: the calendar beast, called

Sir-rush

on the Dragon Gate at Babylon having the body and horns of a bull, forelegs and mane of a lion, head scales and tail of a serpent, hindlegs and feet of an eagle. The calendar has several secret qualities. One is that the number of vowels is increased to seven, the Roebuck’s own number. Another is that II in Ogham makes a ten-stroke letter, and AA makes a two-stroke letter: thus the aggregate number of

letter-strokes for the complete twenty-two letter alphabet is 72, a number constantly recurring in early myth and ritual; for 72 is the multiple of the nine, the number of lunar wisdom, and eight the number of solar increase.

1

72, Mr. Clyde Stacey suggests, is also linked to the Goddess, astronomically, by the seventy-two-day season during which her planet Venus moves successively from maximum eastern elongation to inferior conjunction (closest approach to earth) and thence to maximum west elongation. A third quality is that the proportion of all the letters in the alphabet to the vowels is 22 to 7, which, as has already been mentioned, is the mathematical formula, once secret, for the relation of the circumference of the circle to the diameter.

Before examining the fourth and, for our purpose, the most important quality of this calendar, the poetic relation between Hazel and Apple must be considered. It has now been established that the Roebuck, originally a White Hind, hides in the thicket, and that the thicket is composed of twenty-two sacred trees. The poet naturally asks a further question: ‘But where exactly is the beast lodged in the grove?’

‘Where?’ is the question that should always weigh most heavily with poets who are burdened with the single poetic Theme of life and death. As Professor Ifor Williams has pointed out, it is because the cuckoo utters its ‘Where?’ so constantly that it is represented in early Welsh poetry as a kill-joy: for ‘cw-cw’, pronounced ‘ku-ku’ means ‘where? where?’. It cries: ‘Where is my love gone? Where are my lost companions?’ Curiously enough, the same sentiment occurs in Omar Khayyam’s elegy where the ‘solitary ring-dove’ broods in the ruined palace crying: ‘Ku? Ku? Ku? Ku?’ – the Iranian for ‘where’ being the same as Welsh; and in Greek myth Tereus the hoopoe cries ‘Pou? Pou?’ for his lost brides. ‘Where’ in English is derived, according to the

Oxford

English

Dictionary

,

‘from the interrogative stem

qua’

.

Nearly all interrogatives in Indo-European languages begin with Q (except where Q has been, as in Greek, changed into a P or, as in German, into a W), and in Old Scots ‘where’ is spelt ‘Quhair’. Q, in fact, is the letter of perpetual question. Latin has a fine range of Q’s:

Quare?

Quis?

Qua?

Quid?

Qualis?

Qui?

Quo?

Quomodo?

Quando?

Quorsum?

Quoties?

Quantum?

Quot?

And the Serpent’s dangerous question

Quidni?

‘Why not?’ ‘Where?’ is

‘Qu

ă

?’

But the Muse’s promise to the poet is ‘Seek patiently, and you shall find’, so where else should the Wild Hind be hiding except under the Q tree, which is the Wild Apple?

Valentin Iremonger, the poet, has confirmed this for me in the

Hearings

of

the

Scholars

:

Queirt dano is o chrand regainmnighead .i. abull ut dicitur clithar boascille .i. elit glet quert .i. aball.

‘The letter Q is from a tree named

Quert

, that is to say, an apple tree. As the saying is: “

Quert

is the shelter of the wild hind” – meaning that the apple tree is so.’ An interesting poetic gloss on ‘shelter of the wild hind’ occurs in the same book:

.i. boscell .i. gelt basceall .i. is and tic a ciall do in tan degas a bas

‘that is to say, of the

boscell

,

lunatic, the word being derived from

basceall

,

“death-sense”, for a lunatic’s wits come to him when he goes to his death.’

The comment means that love of the Goddess makes the poet mad: he goes to his death and in death is made wise.

Quert

is not only one of the ‘seven noble sacred trees of the grove’ but is recorded in the

Trials

of

Ireland

as

being, with

Coll

,

the Hazel, one of the only two sacred trees for the wanton felling of which death is exacted. The apple in European literature and folklore is the symbol of consummation, as the egg is of initiation. The 112 days of the Lion flight of months in the Beth-Luis-Nion run

ab

ovo

usque

ad

malum,

from egg to apple, from the end of

Saille,

the nesting month, to the end of

Quert,

the apple month. Thus when the Biblical legend of Adam and Eve reached North-Western Europe, the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil was understood as an apple – not as a fig, despite the fig-leaf context. Adam had eaten from the forbidden tree of intelligence given him by Eve, ‘the Mother of All Living’, and the bards therefore translated ‘fruit’ as ‘apple’.