The Willows at Christmas (4 page)

It was square and squat and quite small and had only one narrow window, as far as he could see, which was barred and set curiously high from the ground. He retraced his steps and saw that there was an old gate, its padlock and chain rusted and broken, which opened upon some steep steps that went down the side of the building and stopped at a low arched door, which had some substantial ironmongery in the way of chains and padlocks, and a little square grille.

“Odd,” he said to himself, “and strange.”

Mole, who was always curious about such things, succeeded in pushing open the gate and venturing down. There was evidence of past flooding on the lower steps in the form of waterborne debris — reeds, bits of wood, rope and the remnants of a swan’s nest.

Standing on tiptoe, he was able to look through the grille. In the dim light cast by the window he could make out a flat stone bench into which were set iron rings, with thick chains hanging from the wall above it. In one corner there was an ancient wooden chair of very sturdy construction, and near it, upon the floor, an earthenware bowl of the kind used by criminals for their ablutions. In another corner the Mole could see a culvert or well of some kind, which he surmised must fall away into the river itself.

“Why, this is a gaol!” said the Mole to himself in astonishment.

This was immediately confirmed when the Mole noticed a battered old sign, its paint peeling and its lettering faded. After considerable effort, he was just able to make out the words,

“Village Pound

—

examine your conscience and your ways all ye who enter here, especially sneak-thieves, pickpockets, felons, traitors, poll collectors, vagrants, nags and witches, to whom every justice shall be shown but no mercy given.”

Underneath this a further inscription announced,

“Renewed by Act of Parliament 1781, this place of retribution and fitting punishment under the jurisdiction of the Lord of the Manor & Court Baron. Hereinafter, as decreed, are listed the trials and tortures to be administered upon the innocent till proved guilty, all in the interests of Justice and for the good of…”

All else was indecipherable. The Mole shivered, for the place had about it an air of past punishment, and long servitude, and was made cold and damp by the proximity of the river. This he now saw flowed hard against the gaol’s walls, and by the look of its colour and the weather it was about to rise even further.

Shivering again, and by now much concerned by the river’s rise, the Mole hurried up the steps and back to the Parish Clerk’s residence.

He was greatly relieved when the door was opened by a tall, gaunt man, dressed in an old-fashioned black frock coat, who in response to the Mole’s query as to whether or not he was the Parish Clerk, responded thus:

“By election and decree and the powers vested in me by the Lord of the Manor I have been, presently am, and shall till my dying day continue to be, unless deposed by statute or proven guilty of treason and or treachery to the Lord of Session, the Clerk of this ancient Parish.”

“You are the gentleman who has signed various notices throughout the Village?” enquired the Mole politely.

The gentleman’s pallid face suffused briefly with pleasure. “You have read, marked and learned them?”

“Some of them,” said the Mole judiciously.

“Then please come into my office,” said the Clerk.

Mole followed him, expecting to be shown into some small room where there might be a few papers, a ledger or two, and, perhaps, a Bible and some Acts of Parliament. But no, they went down a flagged and echoing corridor that opened into a great antechamber with huge wooden benches around its vast perimeter all lit by a skylight. At its far end were three varnished oak doors, the first of which carried the notice “Legal Gentlemen and Witnesses”. The other two were labelled “The Judge” and “The Condemned”.

“Go in there,” instructed the Parish Clerk, pointing (to the Mole’s considerable relief) to the first door, “while I don my robes.”

Mole found himself in a room even vaster than the antechamber. Like the Village Gaol, it was lit by small, narrow, barred windows set high into the walls, through which a cold winter light filtered.

Here and there a little extra illumination was provided by candles in brass holders, which showed it to contain some wooden seats in serried ranks like pews, a witness box, a jury box, a bench behind which were three huge judge’s chairs decorated with heraldic devices, and various other nooks and crannies for court officials.

As his eyes grew used to the gloom the Mole observed at one end a curious set of ancient stone steps much worn by use. They rose towards a door above the general level of the room, which appeared to go straight outside. Above its lintel, in red and gold, were the words,

“Ye Who Have Been Found Guilty, Prepare to Meet Thy Doom!”

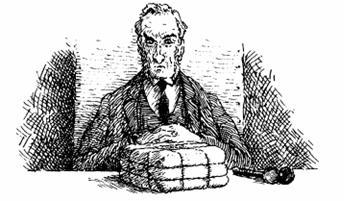

The Parish Clerk appeared suddenly from another door and, to the Mole’s amazement, took what appeared to be the Judge’s seat.

Thumping a gavel upon the Bench and quite startling poor Mole, he said, “Take the witness box!”

The Mole did as he was told. “Your reason for being here?”

“I have come to —”A moment — we must observe the proprieties. Are you willing to take the oath?”

“Er — which one?”

“To tell the truth and nothing but.”

“I normally do,’ said the Mole.

“Good,” said the Parish Clerk. “Then we can dispense with that. Let me repeat my question in simpler terms so that its meaning is plain to you. Why (which is to say what reason can you give) are (which is of the verb ‘to be’ and refers to your corporeal presence) you (which is to say that which is invested in your body namely your soul) here (which refers not only to place but circumstance, and in that, to the cause of your coming)?”

“To collect a parcel that was sent to the Post Office, where I read a notice that said —”

“I know what it said,” said the Parish Clerk testily, since I wrote it myself, from which a witness of normal intelligence might be expected to deduce that I have no need to be told what it said.”

The Mole stayed silent.

“Well?” said the Parish Clerk.

“May I have it, please?” asked the Mole.

“Is this the item?” came the response.

Mole’s interrogator produced a package from under the bench which even from the witness box the Mole could see was addressed to himself.

“Yes, it is.”

“Can you show the court proof of your identity?” asked the Parish Clerk, keeping a firm hold on the package.

“I — I —” said the Mole, rather taken aback. “This is addressed to Mr Mole of Mole End.”

“Yes, that’s me,” said the Mole with some satisfaction. “Can you at least demonstrate that you are that Mole, seeing as there may be others?”

“I have a pocket watch with my name inscribed upon it. It was given to me by my sister the last time I saw her, to mark the occasion when I moved south and took up residence at Mole End.”

The Mole proffered his pocket watch but the Parish Clerk showed no great interest in it.

“It might be stolen and used as evidence against you in your trial as a sneak-thief,” he said wearily, “and we do not want that today, because it is the beginning of my annual holiday. A more substantial trial, for arson, let us say, or capital treason, something I might get my teeth into, now that would indeed make my Christmas a jolly and festive one, for I am due for retirement and have never yet been privileged to act as Clerk at such an occasion. Mere sneak-thievery is not worth the candle (which is to say the festive candle). Ha! Ha!”

The Parish Clerk let out several more of these strange sounds before Mole realised that he was laughing at his own little joke and that it might be as well for him to join in, which he did, much to the Clerk’s pleasure.

“You seem honest, you sound honest and, what is most convincing of all, you look like a mole. In that respect at least you are not an impostor, which is more than I can say for the last gentleman who stood there.”

“And who was that?” enquired the Mole with some interest.

“It was a weasel masquerading as a stoat and attempting to fool us, but failing. I dealt with him severely.”

The Parish Clerk glanced at those steep steps the Mole had noticed earlier.

“He was the first person in one hundred and seventy-eight years to be sent up those steps, though in the event he pleaded with me to let him off with a fine, which I did. I shall not be so weak again! I would not want you, Mr Mole of Mole End, to be so condemned, eh?”

“Er, no,” said the Mole.

“Therefore, take your parcel and cause no breach of the peace during your sojourn in our Village and no harm will befall you, for in the absence of the Lord of the Manor you are under the surrogate protection of the Clerk to this ancient Parish, which is to say myself, the Parish Clerk.”

“I am most grateful,” said the Mole, vacating the witness box and approaching the bench, “and if I might be so bold —”

“Permission is hereby granted,” said the Clerk.

“I am glad indeed to see that the ancient traditions of law, order and justice are still alive and well in our land.”

Again the Parish Clerk’s parchment face coloured with pleasure.

“Quite so, Mr Mole, quite so. And there is another tradition which it is my duty to follow It has long been the custom for myself, as Parish Clerk, and my predecessors right back to Arild the Hornless, who was a Viking, to visit the Public House on the eve of Yule. As my last duty before Christmas has been completed, it would be my pleasure to invite you to be my guest and partake of the Village Chalice, whose depths are plumbed on this sole occasion each year.”

Mole agreed at once, for he enjoyed history and tradition, and saw that once again one need only look in the right place to find the spirit of Christmas.

“I imagine you must know the history of this chamber, and this office, better than any man alive.”

“It may be so,” said the Clerk.

“You made mention of the Lord of the Manor,” said Mole, as the Parish Clerk, still wearing his official robes, came round the side of the bench. “I was wondering who that might be, since I have never heard of such a position in relation to the Village. Is it perhaps an office that is now defunct, the bloodline of that office being long extinct?”