The Wisdom of the Radish (16 page)

Read The Wisdom of the Radish Online

Authors: Lynda Browning

The heirloom Armenian cucumbers we grew and sold at the market couldn't be found at an average grocery store.

So if certain farmers' market produce is slightly more expensive than grocery store fare on a per-calorie basis, that's because the cost reflects the effort of a diversified growing process. Grocery stores can afford to not make money on certain items because a sale brings in customers, and encourages them to spend more money on other profit-making items (particularly processed foods). If I took this approach, I would be working sixty to eighty hours a week for nothing.

Well, I guess I'd be working sixty to eighty hours a week for the privilege of squash rash, cracked fingers, stained hands, an achy back, and a bad tan. For too few showers, filthy fingernails, and torn pants and shirts.

I may have missed my five-year high school reunion, but I knew where my peers were. Business school, law school, med school; at banks and firms and start-ups in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. If you measure success in salaries, cars, and clothes, I am hardly elite; in fact, I lose handily. Stock options and IRAs aren't part of my job description. I don't own a suit. At the moment, I was living off of savings and the generosity of my boyfriend's parents, hoping that some day two risks would pay offâthe financial risk of starting up a farm business from scratch, and the far more terrifying risk that my first multiyear relationship could also be my last. That maybe, after four years of dating and three of living together, we would make it officialâso that when customers searched for the right

word to describe Emmett, I wouldn't have to fill in with that all-too-shallow word “boyfriend” or the awkward “partner,” which may have had an appropriate denotation but connoted a strictly professional relationship, the presence of a cowboy, or the existence of a gay lover, none of which applied to us.

word to describe Emmett, I wouldn't have to fill in with that all-too-shallow word “boyfriend” or the awkward “partner,” which may have had an appropriate denotation but connoted a strictly professional relationship, the presence of a cowboy, or the existence of a gay lover, none of which applied to us.

Instead, I remained the would-be farmer's long-term girlfriend. And my odds for an imminent change of status didn't seem good. Granted, we had, in private, told each other that we wanted to spend the rest of our lives together, but at some point the rest of the world needed to know this. Sure, we'd started to appear in one another's family photos, and it was generally assumed that when we were invited to functions, our other half would be coming along for the ride. But words matter, and few are so public as

husband

and

wife

. There's something about marriage that says: I choose you to be my family, I choose you to be my home. And there's something about society that recognizes and even honors this choice despite all cynicism and pessimism to the contrary.

husband

and

wife

. There's something about marriage that says: I choose you to be my family, I choose you to be my home. And there's something about society that recognizes and even honors this choice despite all cynicism and pessimism to the contrary.

It pissed me off that I wanted to marry him. I was never the girl who dreamed of marrying the boy, and in fact I really never thought much about marriageâaside from a deeply rooted desire to avoid my parents' disastrous versionâuntil now. But while I didn't want to “get married” per se, I wanted to marry Emmett. I very nearly proposed to him at a remote hot spring on the Olympic Peninsula after a hard hike up a mountain, when the light was soft and the whole green world empty of humanity. I told him that later in New Zealand, one late night in our van, hoping that maybe he'd get the hint.

Emmett got the hint just fine, but he wasn't ready and didn't really see the need to marry. You know, since we were already planning on spending the rest of our lives together anyway. Besides, he didn't really want to find himself in the

awkward position of being the first of his close-knit cousins to marry. Why this position could be considered awkward, I hadn't the slightest idea, but Emmett's never been one to draw attention to himself.

awkward position of being the first of his close-knit cousins to marry. Why this position could be considered awkward, I hadn't the slightest idea, but Emmett's never been one to draw attention to himself.

I glanced over at Emmett, counting the bills. It was noon. For the time being, I'd pack up the remaining produce, save some for the local food pantry, and feed the rest to my flock of awkward teenage chickens. That night I'd dip squash blossoms in batter and fry them up for supper, with a side of sautéed beans: peasant food. When I climbed into bed, arms itching and shoulders stinging with sunburn, I'd realize he was no longer an aspiring farmer. I'd roll over and say goodnight with the traditional blown kiss; he'd catch it, send one back. And I wouldn't have to wonder what I actually accomplished that day. Every part of my farmer's body would already know.

Chapter 6:

BAGS AND BAGS

Beans

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

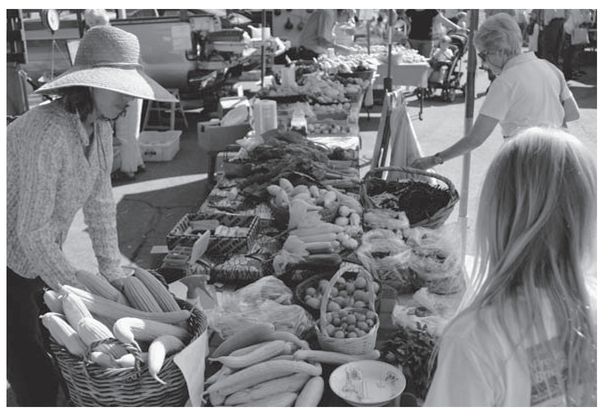

At the Healdsburg farmers' market, three large wicker baskets brimmed with beans.

They were arranged in stripes of color: one basket filled with green Kentucky Wonders; one basket half green with Blue Lakes and half purple with Royal Burgundies; the third basket strikingly split between dark Dow Purple Pod pole beans and lustrous yellow wax beans.

They were arranged in stripes of color: one basket filled with green Kentucky Wonders; one basket half green with Blue Lakes and half purple with Royal Burgundies; the third basket strikingly split between dark Dow Purple Pod pole beans and lustrous yellow wax beans.

The baskets were overfull, heaped high. The beans within them were uniformly young and tender, of a smaller size than those offered by other market stands. No doubt about it: I was starting to assume an air of legitimacy. It was looking like I might be able to do more than kill thingsâmaybe, just maybe, I could grow them, too.

I was beaming over my bean bounty when a tourist couple stopped by.

“Would you look at that!” a big-haired lady exclaimed, tugging on her husband's Hawaiian shirtsleeves (which tourists tend to sport in California despite the fact that they've stopped a few thousand nautical miles shy of Oahu). “I've

never seen beans like

those

before.” She stepped up to the baskets and fixed her eyes on me. “What do they taste like?”

never seen beans like

those

before.” She stepped up to the baskets and fixed her eyes on me. “What do they taste like?”

“You can try one, if you like them raw,” I replied. It was the purple that she was talking about: I plucked a small, tender, plum-colored bean pod from the basket and held it out to her. When a twist of her lip suggested that she wasn't partial to uncooked beans, I shrugged and bit into it. “They're similar to green beans in flavor, although many of our customers agree they're a bit sweeter than the greens.”

“Wouldn't that look just lovely in a salad,” she said, glancing around for a plastic bag.

With that, it was time for my standard honesty-is-thebest-policy caveat. “Just so you know, the purple beans gradually turn green as you cook them. Not the same color as a regular green beanâmore of a blue-green. But depending on how long you cook them, you can end up with a purple-green tie-dyed effect that's quite nice.”

“Interesting,” she said, with an undertone of

only in California

. “Are they all the same price?”

only in California

. “Are they all the same price?”

“Four dollars a pound, mix and match.”

The customer selected a quarter pound of Dow Purple Pod pole beans, a quarter pound of yellow wax beans, and a few Kentucky Wonders. She grabbed two bunches of Swiss chard, handed me five dollars, and continued on her way.

My tourist customer rated about average on the excitement scale. Many shoppers were familiar only with grocery store green beans; our bright display of yellow, purple, and two different varieties of green beans hooked them. Curious, they'd ask questions about flavor, texture, and length of cooking (purple beans are slightly sweeter; yellow wax, slightly more tender; and the different bean varieties cook at similar rates). If these moderately excited customers occupied the upper end of

the income spectrum, they wouldn't hesitate to throw together a big bag of all the different varietiesâand grab some summer squash, salad mix, and French Breakfast radishes while they were at it. If their budgets were a bit tighter, they'd spring for a small samplerâa little of this and a little of thatâand one of our cheaper items, like Swiss chard. Either way, they probably wouldn't have stopped at our stand at all if they hadn't been drawn in by the beansâso the beans not only sold themselves, they also sold whatever other produce these customers happened to pick up. I'm not afraid to admit it: I was a Royal Burgundy bean pimp, using these lookers to hook customers, reel them in, and redirect them to slightly less exotic varieties.

the income spectrum, they wouldn't hesitate to throw together a big bag of all the different varietiesâand grab some summer squash, salad mix, and French Breakfast radishes while they were at it. If their budgets were a bit tighter, they'd spring for a small samplerâa little of this and a little of thatâand one of our cheaper items, like Swiss chard. Either way, they probably wouldn't have stopped at our stand at all if they hadn't been drawn in by the beansâso the beans not only sold themselves, they also sold whatever other produce these customers happened to pick up. I'm not afraid to admit it: I was a Royal Burgundy bean pimp, using these lookers to hook customers, reel them in, and redirect them to slightly less exotic varieties.

Then there were the customers whose admiration of beans surpassed even my own. Often, these folks' parents or grandparents once trellised purple beans in the backyard. They'd never been able to find those beans in grocery stores; my offerings brought them the bright taste of memory, a sense of

heritage, the opposite of loss. One visit from these customers was enough to rekindle anybody's agrarian idealismâI was able to feel as though I was part of something greater than this small farmers' market, some return to a pre-prepackaging Golden Age.

heritage, the opposite of loss. One visit from these customers was enough to rekindle anybody's agrarian idealismâI was able to feel as though I was part of something greater than this small farmers' market, some return to a pre-prepackaging Golden Age.

We transformed from the bug-munched salad stall into a legitimate farm stand at the Healdsburg farmers' market.

Finally, there were the “beans are beans” customers. These constituted my least favorite group. They didn't particularly care what type of beans I was growing or how I grew them. They were unimpressed by the small size of the beans, harvested when young and tender. The one thing that they cared about was the fact that my beans cost four dollars per pound.

It was one thing if these customers were quiet, but a vocal “beans are beans” customer could ruin my entire day. The week before in Windsorâa more meat-and-potatoes town than Healdsburg, and consequently a tougher sell at the marketâa man walked up to the stand, admired my beans, and then asked me the price.

When I told him, he scowled. “You've got to be kidding me. Four dollars a pound for

beans

?” He spat the word out with disdain.

beans

?” He spat the word out with disdain.

I paused, unsure how to respond. Then I remembered. “At Whole Foods, they're selling purple beans for five dollars per pound.”

“Well, I don't

shop

at Whole Foods,” he snapped back, and his sneering remark was so full of retribution it bordered on hateful. He stalked off, and I didn't have the heart to respond. (Although I did spend the rest of the market thinking up my best comeback: “If you're making minimum wage at your job, sir, you're doing better than me.”)

shop

at Whole Foods,” he snapped back, and his sneering remark was so full of retribution it bordered on hateful. He stalked off, and I didn't have the heart to respond. (Although I did spend the rest of the market thinking up my best comeback: “If you're making minimum wage at your job, sir, you're doing better than me.”)

Are beans just beans? First of all, I take issue with the concept of “just beans.” Rhetorically speaking, our society doesn't hold the bean in particularly high regard. The

Oxford English

Dictionary

lists the third definition of beans as “a very small amount or nothing at all,” while

Merriam-Webster

states the second definition simply as “a valueless item.” Beans pop up in various clichés, too. Those who make beans for a living make little. In English and Australian usage, to “not have a bean” is to be broke. In France,

fin des haricots

(literally “the end of the beans”) is an apocalyptic phrase my mother would summarize as “up shit creek without a paddle.” If even the beans have run out, good luck to you, sir.

Oxford English

Dictionary

lists the third definition of beans as “a very small amount or nothing at all,” while

Merriam-Webster

states the second definition simply as “a valueless item.” Beans pop up in various clichés, too. Those who make beans for a living make little. In English and Australian usage, to “not have a bean” is to be broke. In France,

fin des haricots

(literally “the end of the beans”) is an apocalyptic phrase my mother would summarize as “up shit creek without a paddle.” If even the beans have run out, good luck to you, sir.

Common parlance subconsciously pits the customer against four-dollar-per-pound beans. And it's the gastronomic history of the bean that has produced this linguistic bias: beans were, and still are, peasant protein. Those who can afford to dine on meat, do. Those who can't, eat beans.

The bean-eating societal distinction dates back to feudal Europe. The landed class possessed the ability to graze herds of cattle and sheep, or to hunt game on horseback. Those without land were forced to eat more economically, obtaining protein from sources that required a fraction of the growing space. In a time when class distinctions were stark and cruel, beans became indelibly associated with poverty: the stigma of the “poor man's meat” was born. Even today, legumes remain a staple of impoverished people, overpopulated regions, or areas with scant grazing land.

In fact, beans are still at the forefront of international class differences. America is the land of hamburgers. The U.K. is the land of roast (or corned) beef, France of filet mignon, New Zealand of lamb, Australia of outback steaks, Germany of sausage. In developed nations, the dish du jour is usually meat. But throughout much of the third worldâparticularly in Asia and South Americaâmeals often center around some variety of bean. (The black and pinto beans of South America

are, at the species level, taxonomically identical to the heritage beans I grow.) As developing nations narrow the gap between the third world and the first, economists note that they typically undergo a “meat revolution.” In other words, as soon as the residents of developing nations have access to disposable income, their diets shift abruptly away from beans and grains. That first bite into a thick, juicy steak offers not just gustatory pleasure, but also the sense of having arrived: in the twenty-first century, the ability to consume meat still represents a giant leap up the social ladder.

are, at the species level, taxonomically identical to the heritage beans I grow.) As developing nations narrow the gap between the third world and the first, economists note that they typically undergo a “meat revolution.” In other words, as soon as the residents of developing nations have access to disposable income, their diets shift abruptly away from beans and grains. That first bite into a thick, juicy steak offers not just gustatory pleasure, but also the sense of having arrived: in the twenty-first century, the ability to consume meat still represents a giant leap up the social ladder.

But despite the peasant stereotype, beans harbor a certain nobility. If you strip away the pall of history and examine the bean through a biological lens, you'll find that its unique abilities demand a gardener's reverence. From the moment it emerges from the soil, the bean is in a class all its own.

Well, to be taxonomically correct, the bean is actually in a family all its own. Fabaceae, the legume family, is unique in its ability to influence the planet's crucial nitrogen cycle.

Other books

Gentleman of Her Dreams by Jen Turano

Tickled to Death by Joan Hess

The Ascendant: A Thriller by Drew Chapman

Thirst No. 4 by Christopher Pike

Void's Psionics by H. Lee Morgan, Jr

Vexation Lullaby by Justin Tussing

Lost to You by A. L. Jackson

Drekinn 3 - Reaching Rissa by Jana Leigh

Molly Moon & the Monster Music by Georgia Byng

Cake by Derekica Snake