The Wisdom of the Radish (26 page)

Read The Wisdom of the Radish Online

Authors: Lynda Browning

Perhaps in Oregon the customers possess more pluck, but in Healdsburg, few buyers set sail in the rain. As our first customer approached, suited up and clutching a drenched basket, I had to stifle the

Ahoy

that rose in my throat.

Ahoy

that rose in my throat.

“Hi, Care!” Emmett shouted, recognizing the shrouded figure before I did.

“Hi guys,” she replied. “Bit wet today, eh?”

Nearby, a farmer lifted the roof of her tent up with a stick, releasing a giant puddle of water that slammed into the asphalt.

“Thanks for coming,” I said. “Not the best day for a market.”

“Well, if you guys have to be here, we have to be here, too!” Care said.

And in one sentence, Care articulated the attitude that will make the local food movement stick. Although one wet weekend might not break a farm, a fair-weather attitude to local farming very well could. Does the recent popularity of local farms represent a permanent shift in production, or will the farm food fad fade? Farmers' markets have exploded in recent years, and so far the customer base has risen up to meet them. If that base disappears, thousands of new small farms will find themselves stranded: because farming is an investment meant to be recouped and borne out over time, it's not the sort of business that's easy to get into or out of. Economists might not care about the vagaries of their supply and demand curves, but I hope that we're not a country of economists. I have a hunch that the majority of Americans would feel a little tug at their heartstrings, were all the small farms in their neighborhoods to close up shop.

Care bought some broccoli and chard. As I watched customers in fogged-up cars rummage for umbrellas and steel themselves for their wet excursion, I was heartened by the fact

that there were others like her. Over the course of the summer, I'd met people who felt that we needed backyard gardens and farm tours, local livestock and cheerful rows of wormy corn, so that future generations of children could experience a sense of America's historyâand beyond that, an understanding that no matter how technologically advanced our society becomes, someone will still have to grow the food that feeds us all.

that there were others like her. Over the course of the summer, I'd met people who felt that we needed backyard gardens and farm tours, local livestock and cheerful rows of wormy corn, so that future generations of children could experience a sense of America's historyâand beyond that, an understanding that no matter how technologically advanced our society becomes, someone will still have to grow the food that feeds us all.

Customers laughed telling me stories about city kids who thought spaghetti grew on trees. And I laughed in turn when people wanted to buy my “rhubarb,” which was actually rainbow chard. (I laughed partly because I'd be a fool to sell rhubarb with its deadly, poisonous leaves still attached to the stem.) But my younger self didn't know what chard was, let alone that its bright red stems bear some resemblance to rhubarb stalks. I may have gathered from the USDA food pyramid that spaghetti wasn't a fruit, and hence wasn't something that

grew on trees, but beyond that my knowledge of where food really came from ended at the grocery store receipt.

grew on trees, but beyond that my knowledge of where food really came from ended at the grocery store receipt.

Emmett thought that two broccoli heads were better than one.

As a child, my only interaction with livestock came at the San Diego Zoo where, on a lucky day, you just might catch a chick hatching out of an incubator. They didn't mention that the chicks hatched were meat birds destined for the cheetah enclosure, but in retrospect I'm guessing that's the way it went. And rather than finding it repulsive, I think that's pretty damn cool. I'm no expert, but I think kids should know that it takes life to feed other life. For Thanksgiving this year, we bought a heritage turkey from a farmer just across the county border in Mendocino. He had two beautiful daughters, the smaller young enough to count her age out on one hand. She wore a floral print dress and smiled shyly as her dad explained that she was in charge of removing the gizzards from all of the turkeys they processed for customers that Thanksgiving. She wasn't traumatized; she was proud. And I'll bet she really enjoyed her Thanksgiving dinner.

There are plenty of farmers hoping that the country's newfound commitment to local production is a permanent shift. But customers have to be willing to participate in the local food system. Sometimes that involves a hatchet, but for starters, maybe just a rain jacket.

Â

Â

Â

Two hours later, the storm novelty wore thin. My pants were soaked through and my high-tech lightweight rain jacket had sprung a leak. I'd had the sense not to wear my traditional farmers' market Chacos, but not the sense to wear rubber boots. Thus, my lone pair of decent-looking closed toe shoes had morphed into a disaster of overstretched wet leather. My

wool socks squished inside them, and I couldn't feel my toes, just a dull ache. (I might mention that when I was at sea, I was in the tropics. Warm and wet I can handle; cold and wet, not so much.)

wool socks squished inside them, and I couldn't feel my toes, just a dull ache. (I might mention that when I was at sea, I was in the tropics. Warm and wet I can handle; cold and wet, not so much.)

But Care was not the only customer who showed up in the rain. Other regulars stopped by, smiles plastered to their wet faces, and as long as we kept talking, we were all proud of our collective bravery. The people who came made a point to buy something from every stand. The market manager told us not to worry about paying our stall fee, and thanked us for showing up in the rain. Some of the other farmers packed up early and headed home, but Emmett and I figured that since we were here, we might as well stay until the bitter end. And if my fingers and toes were wet and freezing, that was hardly anything compared to the sense of adventure. We were all in the same boat, farmers and customersâand we'd be here holding down our end of the line as long as they kept coming. We weren't at the bitter end just yet.

Chapter 11:

THE PRICE OF A RADISH (AND OTHER ROOTS)

Radishes, Beets, Carrots, and Potatoes

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

The last few minutes before market opening always pass like seconds.

At 8:55 a.m., Emmett rushed around taping up price signs; I bunched bright stalks of rainbow chard, trying to strike a balance between efficiency and aesthetic.

At 8:55 a.m., Emmett rushed around taping up price signs; I bunched bright stalks of rainbow chard, trying to strike a balance between efficiency and aesthetic.

“Four minutes until market,” Emmett said, tapping his watch. “You know what they sayâpile 'em high, and watch'em fly.”

In other words: worry about getting enough bunches on the table, and stop obsessing over each individual bunch. Market stands, including ours, strive for beauty in bounty because customers gravitate toward it. No one will pick a last lonely piece of produceâor even select from a few stragglersâbut everyone relishes sorting through a big pile to find the best item.

I snapped rubber bands around the chard, placed the fifth bunch on the pile, and turned to the next green: Lacinato kale.

“How much are we charging for radishes today?” Emmett asked.

“Maybe we should come down to $1.50,” I said, “But I hate doing that.”

“Well, we can stick to $1.75, and if people complain, drop a quarter. We don't have that many bunches, anyway.”

By 8:59 a.m., I'd bunched a few kales, thrown together four bags of baby lettuce mix, four of baby brassica mix, two of arugula, and I was working on the spinach. At 9:00 a.m., the start-of-market bell pealed: I was up to my elbows in green leaves, pulling spinach out of a harvest bin, tossing aside any stray weeds, and placing handfuls in bags.

Thirty seconds later, I put the last bag of spinach on display and fielded a salad purchase. It was one of our regulars: one half of an arugula-loving gay couple. He grabbed one bag of lettuce mix, one of arugula, and a bunch of beets. “How much are your radishes again? I remember last week they were on the expensive side,” he said, in a friendly way.

I didn't mind him commenting on the price of our radishes: he was good-naturedly honest, and after all he was still buying other produce from our stand. He and I could agree to disagree on the cost, or I could take his advice to heart and drop the price a quarter or twoâbut he didn't make me feel embarrassed about my $1.75 radishes.

On the other hand, last week, when a well-clad woman toting a Starbucks cup picked up a bunch of radishes, asked the price, rolled her eyes, dropped the radishes onto the table, and walked offâ

then

I felt embarrassed.

then

I felt embarrassed.

I'd been thinking about the incident ever since. Her coffee cup in particular gave me pause. This woman was happy to pay $4 for a cup of coffee (nutritional value: nil), but balked at the thought of shelling out $1.75 for a bunch of radishes

(replete with Vitamin C and potassium, among other valuable nutrients).

(replete with Vitamin C and potassium, among other valuable nutrients).

Which explains why I'd been philosophizing about radishes all weekâand yet still hadn't come up with a solid answer to Emmett's question. How much

should

we charge for radishes today? I supposed that it depended on the frame of reference. What you feel comfortable charging or what you are willing to pay comes down to which valueâor valuationâsystem you subscribe to. And as a grower, my value system had definitely undergone a major shift from my days spent on the other side of the stand.

should

we charge for radishes today? I supposed that it depended on the frame of reference. What you feel comfortable charging or what you are willing to pay comes down to which valueâor valuationâsystem you subscribe to. And as a grower, my value system had definitely undergone a major shift from my days spent on the other side of the stand.

One way we could determine our radish price was using simple Econ 101: Supply and Demand. We could charge the price that rested at the intersection of the supply and demand curves: just what people were willing to pay for the amount of produce on offer, and no more. In the real world, which doesn't generally run according to economics graphs, this meant looking at our neighbors and charging what they were charging. (Or, if we wanted to get sneaky, a penny under.)

There was a bit of a problem with this simple system, though. Should we charge what our neighbors at the farmers' market were chargingâor do we price our produce according to the supermarket sale at the Safeway across the street? Or at the health food store down the block? Was a radish just a radish, or were some radishes better than others? Was a farmers' market radish that was not organically certified (but was grown organically) of higher quality than an organically certified Safeway radish that was probably trucked in from Mexico?

Or we could look at our radish price from a grower's perspective. As a farmer, I have a distinct urge to charge people based on how difficult a given plant is to growâand on whether or not it naturally replenishes itself. I'm happy to

provide customers with big bunches of chard for $1.50, even though I've seen other stands charge $2 for half as much. Why? It's simple. Our chard plants will replace the leaves we harvested this morning by next week, and aren't likely to stop doing so anytime soon. Heck, if you drop by the field, I'll give it to you

free

.

provide customers with big bunches of chard for $1.50, even though I've seen other stands charge $2 for half as much. Why? It's simple. Our chard plants will replace the leaves we harvested this morning by next week, and aren't likely to stop doing so anytime soon. Heck, if you drop by the field, I'll give it to you

free

.

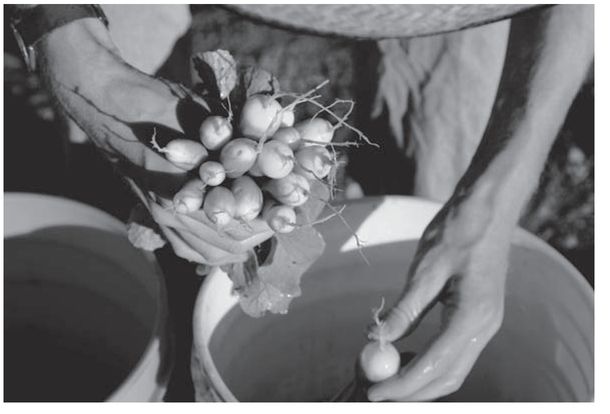

Emmett washed and bunched French Breakfast radishes for market.

On the other side of the spectrum sits the humble radish. Sure, it's a relatively quick grower: ready to go in a month or so. But like all roots and tubers, after I pluck it from the ground it's done. That bunch of French Breakfast radishes that I twist-tie together and place on the table won't give me seeds, won't resprout into a second radish crop, won't do anything other than remove nitrogen and potassium from my soil.

And

that

was the source of my radish angst. I looked at a bunch of radishes and thought: this is seven or eight entire plants. Seven or eight

lives

, if you want to get freaky about it. Was a quarter a plant too much to ask? (And really, what

was the difference between $1.50 and $1.75 anyway, besides a sense of consumer pride?)

that

was the source of my radish angst. I looked at a bunch of radishes and thought: this is seven or eight entire plants. Seven or eight

lives

, if you want to get freaky about it. Was a quarter a plant too much to ask? (And really, what

was the difference between $1.50 and $1.75 anyway, besides a sense of consumer pride?)

But that was applying an external moral framework, I know. It even dared to suggest that a commodity possesses intrinsic value, as opposed to simple market value.

There was one final valuation system we could considerâone that lay between the poetic farmer and the economist. It was based on fuzzy terms like quality, freshness, rarity, and even branding, but this system has weight in today's market. It suggests that a radish is a radishâbut some radishes are better than others, and they come from better places.

First of all, there was the freshness angle. My radishes were plucked from the field that morning, placed under damp towels, and rushed to market; Safeway's were probably picked last week and refrigerated ever since. And my radishes were an heirloom French Breakfast varietyâelongated, pink, with white at the topâwhereas grocery stores usually stick to the run-of-the-mill round, maroon sort. Furthermore, customers were more than welcome to come visit my field, where they could question me about my growing practices. I doubt a grocery store would be so accommodating, because they probably have no idea who actually grows their produce. So my radish offered three things that other radishes didn't: guaranteed freshness, heirloom status, and complete openness about the story behind the food.

Other books

A Texan's Promise by Shelley Gray

Until We Meet Again by Margaret Thornton

The Mango Season by Amulya Malladi

A Regency Christmas My Love by Linda Hays-Gibbs

The Laird's Daughter by Temple Hogan

Green by Nick Earls

Exiled (A Madame X Novel) by Jasinda Wilder

Suffer Little Children by Peter Tremayne

Heaven Sent by Alers, Rochelle

The Wilt Inheritance by Tom Sharpe