The Wisdom of the Radish (28 page)

Read The Wisdom of the Radish Online

Authors: Lynda Browning

It took me several weeks before I started to realize what many a farmer already knows: sheep suck.

Unlike chickens, sheep have the personality of a spoon. I know that a handful of shepherds may argue with me, but I'm pretty sure that the majority of them would agree wholeheartedlyâand that, like me, they end up tolerating sheep because they love their herding dog. Or maybe they delight in mutton or lamb. Or they inherited a sheep farm and

haven't been able to find an idiot to buy it. Or perhaps, for some unfathomable reason, they prefer the aggravating bleat of a hungry sheep to the annoying drone of a lawnmower.

haven't been able to find an idiot to buy it. Or perhaps, for some unfathomable reason, they prefer the aggravating bleat of a hungry sheep to the annoying drone of a lawnmower.

Neither Emmett nor I had ever kicked or hit an animal before; it just wasn't in our character. But on separate occasions, we each took a whack at Teddy. It is extremely difficult to avoid hurting an animal that has just pummeled you with all the force in his hefty, stocky bodyâhas in fact knocked you to the ground that he has conveniently just shat uponâand is backing up to do it again with a look in his eye that comes straight from hell. We figured we needed to go Cesar Milan on his ass: teach him that we, and not he, were the top rams in the flock.

Unfortunately, performing self-defense karate on Teddy was like kicking a boulder. It hurt the foot far more than the ram. Actually, kicking Teddy was worse than kicking a rock: rocks don't laugh at you. After what I thought was a powerful counter-attackâhis head meeting my sole instead of its intended destination, which was the soft spot behind my kneesâTeddy would wiggle his tail, which seemed to be ovine for, “Hee hee; that tickles, silly human.” Then he'd use me as a scratching post and rub his oily, snotty nose on my leg. Then, if I turned my back, the rat bastard ottoman of a sheep would ram me again.

We soon gave up on teaching Teddy a lesson and learned to live in fear of the sound of rapid hoof-beats. Jokes about mutton assuaged my damaged farm ego, although we had no serious intention of eating Teddy. Instead, we kept him long enough to impregnate the ewes, and then got rid of him on Craigslist.

Apparently it wasn't sheep we were missing. We needed something better: kids. Really, what could be cuter than a kid

snuggling with a puppy? We could lock them in the dog crate together so they'd bond with one another. Perfect.

snuggling with a puppy? We could lock them in the dog crate together so they'd bond with one another. Perfect.

Â

Â

Â

And so Ginger entered our lives. When she came home to us she was only about four pounds, bound to her bottle but clearly ready to take on the world. We tucked her into a little bed on the floor, but she immediately got up. She leapt onto the couch and from there to the coffee table, where she scared the living daylights out of our lazy house cat. Jasper fled with fluffed fur and a sulking look that I took to mean, “First a puppy, and now what the hell is this thing?”

Our beleaguered puss had never before come into contact with a Nigerian Dwarf goat kid. Before I went to pick Ginger up from a nearby family farm, neither had I. But as usual, I had performed plenty of research to determine that the Nigerian Dwarf goat was just the right fit for our farm. Originally imported from West Africa in the 1930s, Ginger's ancestors were destined to be conveniently sized zoo food. Over time, artificial selection of the heritage stock resulted in two different breeds that eventually came to be recognized by the national goat registries: Pygmy (a mini meat goat, short and comically stocky) and Nigerian Dwarf (a mini dairy goat, more Barbie than Ken: fine-boned, slender, and possessed of extremely capacious udders).

Nigerian Dwarfsâor Nigis, as the obsessed affectionately call themâhave enjoyed soaring popularity in recent years. Their small stature and gregarious personalities have made them homestead favorites: like chickens, they excel as both pet and producer. And like heritage breed poultry, they are

sufficiently varied so that owners quickly succumb to a “collect them all” mentality.

sufficiently varied so that owners quickly succumb to a “collect them all” mentality.

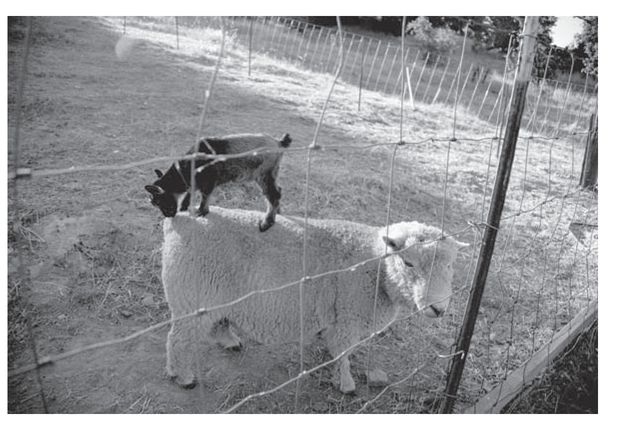

Ginger loved using Teddy as a playgroundâone of the better uses for male livestock I've seen.

Unlike certain goat breedsâfor instance, the all-white Saanenâthere is no color standard for Nigerian Dwarf goats. Each one is different. They come in black, gold, red, white, dark buckskin, chocolate buckskin, cou clair (pale front quarters shading to black hindquarters), Swiss (black and tan, patterned after the Alpine goat), silver, brown, and chamoisee (tan with dark feet, belly, back stripe, and face). And each of these colors can be moon spotted (dabbed with colored spots), broken with white (patches of white in the midst of a pattern), broken with excessive white (large patches of white dominating a pattern), and accompanied by brown, gold, or blue eyes. Each goat's appearance is as unique as his or her personality, and personalities run the gamut from reserved but tolerant

of human contact to lapdog attention whore. The majority of Nigerians fall on the latter end of the spectrum.

of human contact to lapdog attention whore. The majority of Nigerians fall on the latter end of the spectrum.

There are other reasons Nigis make excellent backyard livestock. While full-sized dairy goats can weigh a couple of hundred pounds, a Nigerian gal might top out at fifty pounds and take up approximately the same amount of space as a Labrador retriever. They eat a third of the feed of a regular sized dairy goat, so they're cheaper to maintain. And thanks to their diminutive stature, they're easy to handle, even for kidsâmaking them a popular choice in 4H and FFA families. Best of all, the market isn't yet saturated for these goats, which means it's fairly easy to place all offspring into loving homes: female kids can be sold off as family milkers, while male kids can be castrated and sold off as weedwhacking pets. In other words, unlike many 4H and FFA projects, your baby doesn't turn into sausage.

There's another reason that goats are attractive, at least from a writer's perspective. The goat world possesses its own charismatic language. There is, of course, the goat kid: the only young animal to have bequeathed its name to human children. Goat kids can be further broken down into doelings, bucklings, and goatlings. (Try adding that suffix to any monosyllabic word, and you'll find it instantly becomes 50 percent cuter.) Elegantly, their parents are the female doe and the male buck. Beats the hell out of cow and bull, one of which is frequently used pejoratively and the other of which is typically followed by “shit.” Ewe, ram, and lamb are similarly dull.

And I haven't even touched on the verbs. A goat giving birth and commencing lactation is said to “freshen.” (Try that one out on a pregnant woman: “Baby, don't think of it as labor; you're just freshening.”) Therefore, first-time mothers are “first fresheners”; after freshening, they're also called “senior does.”

Prepositions assume new importance. A kid's pedigree is described as “out of” the dam, “by the” sire. As in, Ginger is out of Gravenstein Apple by Guy Noir, who is out of Raven. So in one sentence, you have ascertained the two most important parts of her pedigree: her parents, and her paternal grandparents. The paternal granddam is particularly important because the most important part of a dairy goat is her udderâand since bucks don't have udders, the potential worth of a sire is tied to his mother's name and reputation, until such time as he has produced enough show-winning daughters to stand on his own.

And of course, while cows are bovines and sheep are ovines, goats are caprines. The word capers right into “capricious,” an adjective that helps explain why both human and goat children came to be referred to as kids. Goat kids and human kids share that unique attention span that is at times nonexistent and at others entirely persistent. Ginger, once she discovers the presence of chicken feed in the chicken coop, will devote her life to trying to get at it. Like the child who has to be read

Goodnight Moon

every free moment for months on end, Ginger seizes every opportunity she has to escape from the pasture and beeline it for the coop. But try getting a goat or a child to do what you want and, if it's not what they want, you'll find the sensation akin to repeatedly thwacking your head against a wall. In short order, Emmett and I trained our dog Kea to jump up only on command (“Dance!”). But when we attempted to convince a doeling not to jump up on us, it was like playing whack-a-mole. We pushed the goat off. We gently rapped her on the nose. And like clockwork, her adorable little cloven hooves popped right back up, stamping our thighs in mud and mashed-up goat pellets. (Ah, goat pellets.

Another reason that goats beat the heck out of cows. Like sheep, they defecate in convenient, inoffensive, dry pellets.)

Goodnight Moon

every free moment for months on end, Ginger seizes every opportunity she has to escape from the pasture and beeline it for the coop. But try getting a goat or a child to do what you want and, if it's not what they want, you'll find the sensation akin to repeatedly thwacking your head against a wall. In short order, Emmett and I trained our dog Kea to jump up only on command (“Dance!”). But when we attempted to convince a doeling not to jump up on us, it was like playing whack-a-mole. We pushed the goat off. We gently rapped her on the nose. And like clockwork, her adorable little cloven hooves popped right back up, stamping our thighs in mud and mashed-up goat pellets. (Ah, goat pellets.

Another reason that goats beat the heck out of cows. Like sheep, they defecate in convenient, inoffensive, dry pellets.)

A Saanen, the Holstein of the goat world, can produce seventeen pounds of milk per day, while a highly productive Nigerian might produce five. And although you might think that more milk is better, that's not necessarily true for the home goat keeper unless he or she happens to have swine to feed all the extra milk to. And there's a difference in milk quality, too, which is important for the home cheese maker. The Nigerian's milk has the highest butterfat content of any of the dairy goats, so there is less whey byproduct.

Which reminds me, I haven't yet gotten around to making that chèvreâbut that's something I could get into.

Â

Â

Â

Ginger was quickly followed by Sedona, Pippi, Calamari, Zoe, Tuxedo, E squared (Emily and Elizabeth, purchased as prenamed adults), and our aspiring herd sire, Gobi. Aspiring because when he came home, Gobi weighed just a few pounds, his testicles were the size of peanuts, and based on an embarrassing accident perpetrated on my lap on the three-hour drive homeâhe managed to diarrhea all over me as soon as we pulled away from his farmâit was amply clear that he wasn't going to be seeing much action anytime soon.

“You brought home another one that needs a bottle?” Emmett asked, shaking his head. “I thought they were all going to be weaned.”

Surprise!

“And wait a second. How many goats do you have in the car? You said you were only getting three.”

Surprise!

“Four. But this one reminded me of Tux.”

Word to the wise: never buy animals while in a state of grief. To do so is to ensure that common sense will be subsumed by the desire to fill aching voids with adorable creatures. A couple of weeks before bringing home our new goats, we left for the weekend to attend Emmett's cousin's wedding ceremony. It was an agonizing decision: although I wanted to accompany Emmett to the wedding, leaving the animalsâand the vegetablesâin the care of someone else is stressful. We provided our caretakers with written and verbal instructions, physical demonstrations, and reminded them multiple times to check under the porch for eggs and broody chickens who'd been trying to spend the night down there. And then, after shelling out fifty dollars per night for the service, we worried about the farm the entire time we were gone.

When we arrived back home at midnightâafter a fivehour flight and an hour-long drive from the airportâwe went straight to the coop to check on the girls. Hope? Check. Joy? Check. Two Wyandottes? Check. Tux? I ran my hand over every single chicken in the coop, climbing into the back corners to see if for some reason she was there instead of on her usual perch in the front. But Tux was missing. We spent two and a half hours with flashlights searching for her in the dark and calling her name. I was crying even before Emmett found her wings, head, and feetâthe spine there, too, but the torso skinned and disemboweledâacross the road in the vineyard. We buried her that night.

The caretakers hadn't collected a huge pile of eggs that were beneath the porchâwhich would have further persuaded broody Tux to try sitting on them overnight instead of returning to the coop, where she would have been protected from

predatorsâand clearly failed to follow verbal and written instructions.

predatorsâand clearly failed to follow verbal and written instructions.

Emmett felt terrible. This had been my worst fear before leaving for the wedding. So he couldn't exactly begrudge me a black goat with a little white star on her head who followed me around like a puppy dog and climbed into my lap.

Â

Â

Â

Life with seven kids quickly settled into sweet, comforting farm routine. I quickly learned their languageâthe “mehh” that meant, “Hi, mom!” or the “MEH!” that meant, “More alfalfa, please, we're out!” I could tell them apart by the sounds of their voicesâTuxedo's shrill urgency, which hovered somewhere between a yodel and a bleat, Pippi's piercing whine, Sedona's reserved, polite call.

They progressed quickly into puberty, and before I knew it, the girls were humping each other while, in a separate pasture, Gobi watched them and licked his penis. When we placed Elizabeth in the pasture with him, she was approximately twice his size, and Gobi seemed to prefer watching the doelings hump each other to mating with Mrs. Robinson. We were eager for him to impregnate a female goat, because we wanted to start milking as soon as possible.

And then one day, a fascinating awakening took place before our eyes, or at least before Emmett's eyes. I was at workâI had taken an office job to fund our off-season investments in seeds and livestockâwhen I received an e-mail entitled “In other bright news.” Emmett typically writes in grammatically correct sentences, and he's not normally prone to graphic description of any sort, so this e-mail was rather out of character.

Other books

The Greek Rule (The Greek Series) by Nakis, Aleka

Asmodeus: Demon of Lust---Part One (Princes of Hell) by Humphreys, Sara

Fixation (Magnetic Desires Book 3) by Murphy, Misti

Imager's Intrigue: The Third Book of the Imager Portfolio by L. E. Modesitt

The White Horse by Grant, Cynthia D.

The Custodian of Marvels by Rod Duncan

Recollections of Rosings by Rebecca Ann Collins

Dead Air (Sammy Greene Thriller) by Deborah Shlian, Linda Reid

A New Hope (The Second Chance Series Book 2) by Escue, Christina

Paladin of Souls by Lois McMaster Bujold