The Work and the Glory (520 page)

Behind them, the wagon flap on Matthew’s wagon flew open and Christopher came bursting out, followed by the other children. “It’s the band, Papa. They’re gonna play. Can we go!” Christopher was seven now and proving to be as husky as his father. His eyes were wide and his face infused with excitement. “Please, Papa.”

Emily and Rachel had jumped to their feet and were staring off in the direction of the sounds, which were swelling in volume now with every moment. “Is there going to be a dance?” Emily said, her eyes shining.

Lydia groaned in mock horror. “You can think about dancing after today?”

“Oh, yes, Mama!” came the instant reply.

In the distance, the trumpeter started the first line of “Now Let Us Rejoice,” then let it disintegrate into a series of trills and runs.

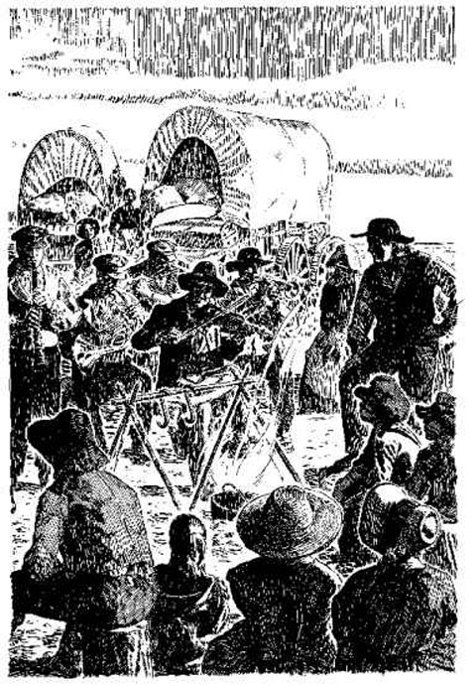

People were coming to their feet, and tent doors and wagon flaps were being opened all across the camp now. People were pointing and calling out to one another. Just then a man came riding toward them on a horse. He was hollering something as he passed. They turned to listen. “Concert at the main campfire in five minutes. Brother Pitt has his band together. Concert in five minutes.”

Nathan turned to his mother and smiled. “What do you say, Grandma? Shall we go and hear Brother Pitt tonight?”

Mary Ann started to shake her head, then immediately changed her mind. If she begged off, claiming she was tired—which she truly was—she knew what would happen. Nathan would volunteer to stay with her. Lydia would then insist on staying with him. Then Joshua and the others would decide maybe it wasn’t such a good idea after all, and none of them would end up going. She turned and looked into her grandchildren’s eyes. They were shining brightly in the firelight, and they were filled with pleading. She couldn’t help it. There was a soft laugh and she got slowly to her feet. “But of course we’re going.”

As the children whooped and threw their arms around her, Jenny stood and spoke up quickly. “I’ll stay with the babies. You all go on.”

She waved her hand as the other mothers started to protest. “No, really. Another night, when I have Matthew with me, then one of you can stay and we’ll go.”

That settled it. As one they moved off, Joshua taking one of his mother’s arms, Emily taking the other. The whole camp was stirring now as people came out of their tents or climbed down from the wagons and streamed toward the central part of camp where the Twelve had their wagons. And Joshua, watching the other families moving together, talking excitedly, felt a great longing for Caroline and the children. It was hard enough being gone from them, without times like this. And yet, at the same time, he also felt a grudging admiration for Brigham Young’s wisdom.

Brigham hadn’t missed much. He had organized a pioneer company under the direction of Stephen Markham, the members of which would go ahead of the main camp, breaking trail, building bridges, securing work and food, preparing ferries for the wider rivers. Bishop George Miller, leading a dozen or so wagons and three or four dozen men, had moved out a few days before, the surest sign that Brigham was serious about starting west. Brigham had asked Hosea Stout, the chief of police in Nauvoo, to create a “police” company. These men, most of whom owned rifles, served as guards, provided protection for the camp, and dealt with those few disagreements that could not be settled by the captains of tens or captains of fifties. The creation of a police company was sobering evidence that Brigham Young was still worried about the threat from their enemies. There were also commissaries appointed to secure food, treasurers to handle the finances, wagon masters, blacksmiths, carpenters, and a dozen other positions required to keep a large body of people moving.

And there was William Pitt and his brass band. And who would have guessed that that would be part of the organization? In Nauvoo, Pitt and his band, while perhaps not the finest in the land, had been immensely popular. When Pitt, a British convert, came to America, he brought with him a large collection of music for brass bands and found many opportunities to use it. The Nauvoo Brass Band, as it was called, played grand marches, quicksteps, and gallops, as well as the hymns. They played for dances and gave concerts at the Masonic Hall, which served as the city’s cultural center. When it came time for the exodus, Pitt had specifically been asked by Brigham Young to keep his musicians together in one company so that the band could continue to function on the trail. Joshua had spent years hauling freight across the back roads of western America. He knew how lonely the trail could be and how important morale was. The decision to keep the Nauvoo Brass Band together and functioning was already proving to be a brilliant move.

And then, even as they approached the central campfire, the band began to play a song that in the last few months had become one of the most popular among the Saints. They heard the distant sounds of applause and cheers. Holding on to Joshua’s arm tightly as they moved across the frozen ground of the camp, Mary Ann tipped her head back and began to sing. Momentarily startled, Lydia laughed, then joined in. Then it was Emily and Rachel and others around them. In moments, the whole stream of people moving toward the fire were singing lustily.

The Upper California—Oh, that’s the land for me!

It lies between the mountains and the great Pacific sea;

The Saints can be supported there,

And taste the sweets of liberty.

In Upper California—Oh, that’s the land for me!

Kathryn Marie McIntire Ingalls was worried, and Peter could see it in her eyes, though her head was high and her chin firm with determination. As he pushed her along the boarded walk toward the home of James Reed, he sought for the words that might make her less anxious, but he sensed that unless his attempt was positively brilliant, it would do more harm than good, so he said nothing.

As they approached the large brick home in one of the finer neighborhoods of Springfield, Illinois, he saw her shoulders come back and she drew a deep breath. They were not yet to the corner of the Reed property, with its wrought-iron fence and its beautiful flower gardens. She turned her head. “All right, Peter. I’d like to walk from here.”

He frowned, but immediately nodded. “All right.” He stopped the wheelchair and untied the crutches from the back of it. Stepping around to face her, he held out his hands.

There was a sudden shake of her head—quick, emphatic, stubborn. “Don’t help me, Peter, someone may be watching.”

He took a breath, letting it out slowly, and handed her the crutches. Then he stepped back to brace the chair so it wouldn’t roll. It was not as if he hadn’t seen this stubborn streak in her before they were married. It fact, he had nearly lost her when she thought he might be marrying her out of pity. But in the four and a half months since then, he had come to understand just how fiercely it burned within her. And while sometimes it exasperated him beyond measure, he understood its source and loved her all the more for her determination to make the best of her handicap.

And she was getting very strong. He watched as she put one crutch under her arm and then hoisted her body up, steadying herself on the arm of her wheelchair. With a little flip of her upper torso, the second crutch was in place and she moved away from the chair. “All right.”

Looking around, Peter found a place beside some bushes and pushed the chair into them, well off the walk so it would not be in anyone’s way. When he turned back, she was already moving forward with smooth, even motions. He walked forward to her side. “You really are getting very good, Kathryn.”

“Thank you, dear.” She smiled one of her prettiest smiles at him, but it darkened almost instantly. “I just don’t want the Donners to think Mrs. Reed made a mistake when she hired me.”

“They won’t. And even if they did, Mrs. Reed and the children think you’re wonderful. She won’t change her mind.”

“I know,” Kathryn said, her jaw thrust out, “but I want them all to know that I am not going to be a burden to anyone.”

He grinned at her. “Are all the Irish like this?”

She flashed him a smile back. “All right, Peter. I’ll behave myself.”

They had reached the gate that opened onto the walk that led to the front door of the home of James Reed. Peter moved forward, opened the gate, and stepped back, holding it open for Kathryn. She gave him an impish look, that look that reflected so well her temperament. “Well,” she said with mock primness, “I don’t give a fig what anyone else thinks. We have been hired by the Reeds to help them out, and all we need to do is please them.”

“Which you have,” Peter said firmly, ignoring the fact that she was lying shamelessly to herself.

As they reached the ornately carved wooden door, she hesitated, and he could tell that her bright courage was wavering just a tiny little bit. Peter touched her elbow. “It will be all right, Kathryn. You’ll win them over, just as you won over Mrs. Reed.”

She bit on her lower lip for a moment, then again brought forth her best smile. “But of course, Mr. Ingalls. What else would you expect from the woman you married?”

There were about twenty people squeezed into the large and sumptuously furnished parlor of the Reed home. Originally, this whole thing had started in a reading society. During the fall and winter of 1845–46, westward fever began to sweep the country. Newspapers wrote articles about that great unknown that lay west of the Mississippi River. Books were published and became immensely popular. A few months earlier, Mrs. George Donner had persuaded her reading society group to turn their focus to readings about the West. Very quickly the fever had infected most of the group.

But it was no longer just a reading society. The decision had been made. Now it was planning time. Most present came from three families. The rest, like Peter and Kathryn, were the few “bullwhackers” and assistants who had been hired so far. There were even some of the older children present, wide-eyed and a little breathless to think that this was really going to happen. But it was the Donners and the Reeds who were behind it all. George and Jacob Donner were brothers. Jacob, the older of the two, and his wife, Elizabeth, had seven children who would be accompanying them (two of these being Elizabeth’s by a previous marriage). George had lost his first two wives and married again to the present Mrs. Donner. He had eleven children in all, but many were married. Only five would be going west. James Reed and his wife, Margret, had four children and Mrs. Keyes, the aged and infirm mother of Mrs. Reed.

As Peter looked around the room, there was no question but what the Donner brothers and James F. Reed were well-to-do men. The Donners were both older men, probably in their sixties, Peter guessed, and had made good as farmers in western Illinois. Reed, considerably younger at forty-five, was probably the richest of the three, having had success in such enterprises as furniture manufacturing and railroad contracting. Even now it staggered Peter to think that these men were not selling all their property to finance their trip. George Donner had been trying to sell one of his farms, but even if that fell through, it wouldn’t stop him from going. So if the promise of California proved to be ephemeral, they would still have something to which they could return. That left Peter a little bit dizzy. He had seen the outfits these three families were putting together. Brand-new wagons. The finest of Durham steers, already well proven as draft animals. They would have new tools, ample supplies of food, riding horses, milk cows, beef cows. An average wagon and team, with supplies enough to take one west, cost about seven hundred dollars. But each of these families was taking not one wagon but three, which meant they were easily spending twice or three times that amount; and the fact that they did not need to sell off land in order to do so took Peter’s breath away.

This was the first meeting to which Peter and Kathryn had been invited, and they sat quietly in the corner, listening to the discussion, both of them a little cowed by their surroundings and their company. George Donner stood before them, waving a book in the air as though it were a flag and he was using it to call them to battle.

“Listen to this,” he cried loudly. “Just listen to this.” He opened the book and started thumbing for the place he wanted.

“Tell them what book it is, Mr. Donner,” Tamsen Donner told her husband, with a tolerant smile toward the others. “That’s important.”

He shoved it toward them, spine first, as if they could read the small print from that distance when it was bobbing and dancing like a living thing. “It’s called The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California. The author is Lansford Hastings, one of the few men who have been west and learned the country.”

Now, compliance to his wife’s request done with, he opened the book, thumbed a few more pages, then found his place. “He says here that the climate of western California ‘is that of perpetual spring.’ And over here”—George turned the page over—“he says that since there aren’t any marshy regions in California, ‘the noxious miasmatic effluvia, so common in such regions, is here, nowhere found.’ ”