The Year Money Grew on Trees (17 page)

Read The Year Money Grew on Trees Online

Authors: Aaron Hawkins

I didn't know what to say. I could think of a lot of words to describe what I was having, but "fun" wouldn't really pop out. I thought of our freezing fingers, stinking shoes, sleepless nights, and poison showers. Then I smiled and simply said, "Yes."

"Good!" she said. "I'm glad. Even if you don't make any money, at least you're having fun. And learning something too. Like the time you dug up my hydrangeas. I'll bet you'll never do something like that again after the lesson I gave you. Sometimes things don't turn out like we hope, but we have to look on the bright side and appreciate the experience."

The hydrangeas. I had tried to forget them, but the whole scene recrystallized. She refused to pay me and kept yelling, "Stupid! Stupid!" If I didn't count my dad, it was the first time an adult had ever said anything like that to me. The next time I saw her, she acted like nothing had even happened and I was supposed to work on her yard again. Hydrangeas. Stupid. I looked at Mrs. Nelson and put my hands up to my face with the palms facing her. I wanted to show her the calluses and blisters I had earned as part of the latest experience. I don't think she got it.

It was strange, but the less contact I had with Mrs. Nelson, the friendlier her son, Tommy, became. When he drove out to see his mom, he would often walk over and talk to me or Amy if he saw us in the orchard. At first, it seemed as if he was inspecting us, but eventually he acted sincerely impressed by what we had done. He had even bothered to learn the names of my sisters and younger cousins. He stopped by right after Sam had

done his discing and found us repairing some of the little ditches Sam had destroyed.

"My old man would have really gotten a kick out of this. It's never looked this clean!" Tommy called to us as he came walking up.

"Thanks," I replied, and I had to agree with him. The tops of the trees themselves were a bright green. The ground around them was a rich wet brown with manure peppered over it. Against the bare earth, the trunks looked strong and wide. If you bent low, you could see from one end of the orchard to the other through the weedless space.

"Didn't it look like this when your dad was working on it?" I asked Tommy seriously.

"Nah. I don't think so. It was always more of a hobby to him than anything else. Sometimes he'd just quit doing anything out here in the middle of the year."

"Really?" I replied, and scanned his face to make sure he was telling the truth. He wasn't even smiling, just turning his head around and looking at the trees. "Tommy, would you like to help us water or something one of these times?" I asked him hopefully.

He laughed a little. "Me? Oh, I don't think I'd be very good at it. I'm sure my mom has told you that a hundred times."

"But you helped your dad sometimes, right? So you've seen how everything is done."

He laughed again. "I helped a little but not very willingly. I don't think I'm much of a farmer."

"That's what my dad says about himself."

"Maybe it skips a generation."

He walked back to his car and zoomed off. For no particular reason, Michael pulled a small apple off a tree and threw it at the cloud of dust Tommy left.

Dump Boxes and They're All Mine

August apples are dangerous. They're smaller than a baseball and just the right weight for throwing. Sam and Michael had been working on their arms all summer, and I was constantly avoiding shots to my head. An August apple can hurt you in other ways too. Earlier in the summer, they're sour enough to make your lips pucker. But by August, a hint of sweetness emerges that reminds you of that apple's potential. You can forget about the sourness and get way ahead of yourself.

One day Sam and Michael had a contest to see how many August apples they could eat at one time. In our

orchard, half of the trees produced green apples and half a green-red combination. They chose the all-green ones. Sam won by eating twelve. Even before he was finished, he was complaining that his stomach hurt. He and Michael spent the next two days moaning and running back and forth to the bathroom.

After the green apple experience, Lisa became very upset about what she called "wasting apples." "All the apple throwing and eating till you're sick is like throwing money away," she lectured. "Think about how much each apple is worth. Jackson, how much is each apple worth?"

I looked back at her like she had asked me to build a TV. I had no idea how much an apple was worth. All I knew was we needed enough of them to add up to the $8,000 that the contract said I owed Mrs. Nelson.

"And I've been thinking, who are we going to sell these apples to, anyway?" she continued.

I had been wondering the same thing and couldn't put the topic off much longer.

"Maybe to the supermarkets or something," I suggested, watching how the others would react to the idea.

"I think supermarkets get their food from places like California," said Amy.

"We could sell them to an apple juice company," offered Sam.

"Or sauce," said Michael.

"Yeah, maybe," I said, trying to sound very thoughtful.

"Why don't you ask Brother Brown where he sells his?" asked Lisa.

"Why would he want to tell us that?" Amy asked quickly. "If we did the same thing, that would be competition and he'd lose money."

I figured she must be right. It was hard for me to think of Brother Brown as competition, but maybe it would be wrong to ask him about selling apples.

"I think we should start with the supermarket, then. Some of us could go with my mom and check things out," I said. By some of us, I really meant Amy and me, but when I asked my mom about it, Lisa and Jennifer insisted on coming too. We went on my mom's regular shopping day, and Amy got to sit in the front seat of the car.

There were a few different supermarkets in Farmington, but my mom always went to Safeway. While she started to load up her grocery cart, the girls and I went to find the produce department.

"I've never noticed before how many different kinds of apples there are," said Lisa as she examined the stacks of fruit in different colors. "What kind do you think ours are?"

"Half are green, so maybe Granny Smith or Golden Delicious. The red ones, I don't know, maybe McIntoshes," said Amy as she ran her fingers over them.

"Look for someone we can talk to," I whispered to Amy.

"How about that guy," she said loudly, and pointed to someone stacking up potatoes about fifty feet away.

We walked closer to him and noticed that he was young, maybe just out of high school. He wore a neat apron and sort of hummed or whistled to himself as he stacked.

"We want to talk to you about your apples," Amy said boldly from behind him. He swung around, and Amy, Lisa, Jennifer, and I were standing in a line staring at him.

"Uh ... what?" he asked, looking confused.

"Can you tell us where you get your apples?" Amy asked loudly.

"I don't know, maybe Washington. They grow lots of apples there."

"Do they just arrive in a big truck or something? Do you have a big pile of them in the back?" Amy continued.

The potato guy laughed. "No, they come in boxes like this," he said, kicking a box of pears with his foot. "That's a bushel."

"So how much would you pay for a bushel of apples?" Lisa broke in.

"Don't ask me, I just put 'em out."

"How many apples in a box?"

"Mmmm. Maybe a hundred."

"Do you ever sell any apples grown around here?" I asked.

"I wouldn't be able to tell. If you guys really want to know, I could get my manager. He does more of the ordering and that kind of stuff."

"Okay," said Amy quickly.

He walked toward the back of the store and in a few minutes came back with another man who must have been the manager. He was middle-aged, with pale skin and very dark hair combed to one side.

"I hear you want to buy a truckload of apples," the manager said as he walked up. He was trying his best to be funny, but he sounded more like a bad actor in a school play.

Amy looked at him and frowned. "Actually, we thought we'd sell

you

a truckload of them," she said.

The manager stared at her, wearing a creepy grin. He moved his eyes up and down her until she looked away.

I decided I should speak up. "Do you ever buy locally grown fruit and vegetables to sell here?"

"Nope!" he said, still looking at Amy. "All of it comes from our central distributor. Can't be sure that anything else would be safe or high quality."

"We've got a lot of apples that are really high quality, and we've been spraying for worms and bugs regularly."

The manager finally turned and looked at me. "Look, this isn't some kind of flea market. We can't just go buying any old thing off the street. And where are your parents? Shouldn't they be worrying about selling the family crops?" He giggled to himself.

"Then can we talk to the distributor or something? Maybe call him?" I asked hopefully.

"Go ahead if you can find the number. Now, I've got to get back to some real work," he said. He took one last long look at Amy and turned and slumped off slowly, as if he were hoping we would beg him to come back.

When he left, the young potato guy turned to us. "Sorry about that. He wasn't much help."

"Not really," I agreed. "You don't happen to have that distributor's number, do you?"

"No, but maybe you could look in the phone book

or something or call the main line to the store and ask."

"We'll try it," I said. "Do you think we can have a couple of those extra boxes?" I asked, pointing to some boxes he had finished unloading.

"Sure, go ahead," said the potato guy.

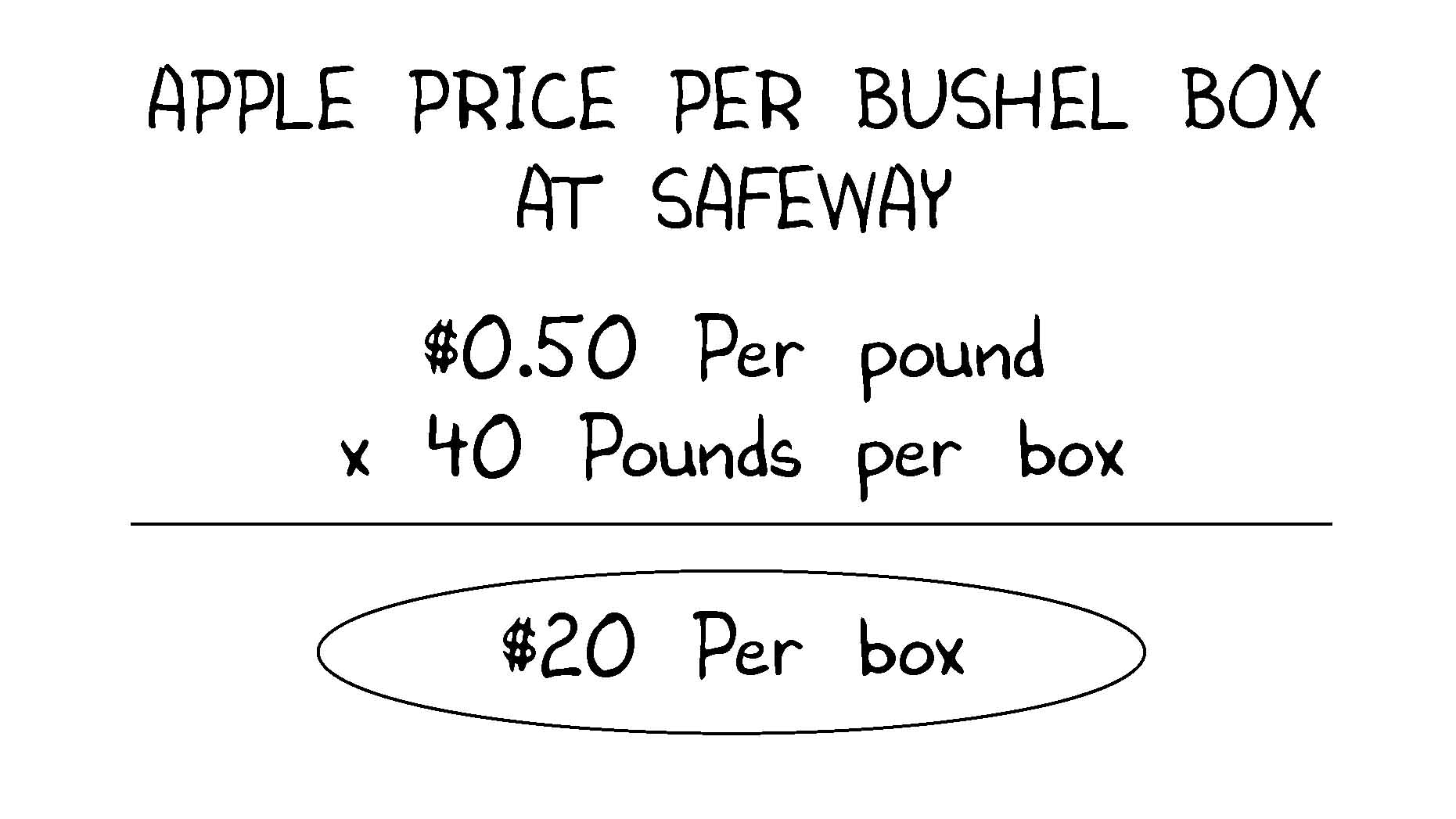

We collected as many empty boxes as we could, including a few apple boxes. We also wrote down what Safeway was charging per pound for apples: fifty cents. The side of the apple box said there were forty pounds per bushel, so we had a pretty good idea of what a bushel of apples would cost at Safeway. It was close to the $25 Mrs. Nelson had mentioned when she was talking me into the orchard idea.

All of our collected boxes plus Mom's groceries wouldn't fit in the trunk of the car, so we had to ride home with a few of them crammed under our feet and on top of our laps. It was depressing to think about not

having a place to sell our apples, and everyone was quiet in the car, staring out the windows.

It's funny how sometimes you can see a thing hundreds of times and never notice it. Then one day you really look at it, and it becomes the only thing you can see. That happened to me just as we were leaving Farmington. On the side of the road, people were selling something out of the back of their car. They had a little sign that said

BEANS AND MELONS

. All of a sudden, I remembered seeing that car almost every time we went to town.

"Hey, Mom," I asked, "would you ever buy fruit from someone selling it on the side of the road?"

She thought for a few seconds. "Well, maybe. It would probably depend on who was selling it, what it looked like."

"Would you pay the same price that you would in the supermarket?" I asked.

"No, because it would require an extra stop. So it would have to cost less. Why?"

"Just kind thinking," I replied.

I noticed several more cars selling fruit before we got to Fruitland. I saw someone with a

WATERMELONS

sign in the distance and asked my mom if we could stop.

"I don't want any watermelons," she said.

"I just want to talk to them a little bit."

She pulled off and said she would wait for five minutes.

I had Amy do most of the talking. We found out that the watermelon sellers were a mother and young daughter. They were selling watermelons now but would sell all kinds of fruits and vegetables during the summer and fall. They raised some of it themselves and would drive out of state to buy things like oranges.

"Do you sell things by the pound?" I asked.

"No, by the box," the woman answered.

"I think that settles that," I said, walking back to the car.

"What settles what? What are you talking about?" asked Amy.

"How we're going to sell our apples."