The Year Money Grew on Trees (25 page)

Read The Year Money Grew on Trees Online

Authors: Aaron Hawkins

***

Despite the cold, I kept watching Mrs. Nelson's house from the orchard. Nothing happened for the rest of the week, and I couldn't even see any movement through her windows. I decided on Monday afternoon that I might as well fill up some boxes with apples for my mom and aunt before they all fell to the ground. I grabbed more of my dad's non-fruit boxes and went to work. I was able to keep an eye on Mrs. Nelson's since picking had almost become automatic and I could do it mostly by feel.

A couple of hours after I started, Tommy's car pulled up to his mom's house. He went inside, and then a few minutes later started walking down the dirt lane to my

house. He saw me in the orchard and headed toward me. As he got closer, I moved down the ladder I was on and stood clutching it with one hand. I thought of running to get Amy. I hated to be alone if he was going to confront me.

Tommy reached my ladder, huffing loudly with his breath visible in the cold air. "Back out here, huh?" he began.

"Thought I'd pick a few of the leftovers for my family before they drop."

"Well, might as well go ahead and give you this," he said, and pulled a manila envelope out of his coat pocket.

At first I thought it was the envelope I had left on Mrs. Nelson's doorstep, but then I saw it had different writing on it. I took it from his gloved hands.

"Go ahead and open it," he said.

"What is it?" I asked as I turned over the flap on top of the envelope. I pulled out the papers inside. They looked like legal documents or something, and I could see numbers written on them.

"It's the deed to the orchard."

"It is? What does that mean?" I asked while thumbing through the papers.

He pointed to the last page and said, "That's my mom's signature down there at the bottom. It means all you have to do is sign next to it and the orchard's yours. Everything else has been filed with the county already."

I looked up at him in disbelief. "Really? Aren't you mad about this or something?" I blurted out.

"Me? Why should I be mad?"

"Wasn't it supposed to go to you?"

"Maybe when my mom dies, but she'll probably outlive me just to prove a point. Actually, I'm kind of glad it's going to be yours. Then she can't keep nagging me about it."

I stared back down at the documents. "Well, is she mad?" I asked him.

"I don't know about mad. Maybe a little embarrassed and feeling silly. I'm sure she'll get over it next spring when the trees are blooming." He said this last part trying to imitate her voice.

"You know when she told me about your little agreement," Tommy continued, "I mostly felt sorry for you. My mom has no idea what it takes to make any money doing something like this. That $8,000 sounded impossible to me. I didn't want to tell you that because you looked so eager that I hated to discourage you."

"What did you think was going to happen?"

"I thought you would just kind of give up. When I saw the $8,000, I was floored. At first my mom wanted to think of a way not to turn over the orchard, but I kept telling her she'd be the laughingstock of the whole state if people found out she cheated some kid. I figured she owed it to you, no matter how cuckoo the agree

ment was. Of course, the only thing that really worked on her was threatening to stop coming out to see her."

"Thanks," I said, although it didn't sound like enough.

"And by the way, I made her sign over the water rights too. This place isn't much good without them."

I didn't really know what water rights were, but I figured they must have something to do with the canal.

"Thanks again, Tommy. How about the other stuff, like the ladders?"

"Go ahead and keep them. She's not gonna need them for anything."

He looked down at my hands that were still holding the envelope and then looked around the orchard. "So how'd you do it?" he asked. "I mean, that's a lot of apples."

I thought hard about his question and about everything that had fallen into place over the past eight monthsâthe library book, my cousins and sisters, the old Ford tractor, the apples not freezing, Brother Brown, Jimmy, the free boxes at the dump. Take away one of those things, and we probably would have failed.

"I guess I was pretty lucky."

"Whatever it was, I'll always be impressed," replied Tommy, nodding his head.

I looked down at the envelope, and it suddenly felt heavy. Tommy deserved some of the credit too. "If you didn't stand up for me, well, I don't know what..." I trailed off.

Tommy shuffled his feet and looked at the ground. "Ahhh, I figured I owed it to my dad. I never did help him like I probably should have. I dunno, I guess I regret what he probably thought of me, how we never seemed to have anything in common. If I plowed up these trees, he'd probably haunt me forever. It's better having you worry about them."

Tommy held his hands up to his ears like he was trying to keep them warm. "I gotta run, before I freeze." He turned and started walking away. "Hey, Jackson," he called, "just don't turn it into a trailer park, okay? You'd make me look like a moron."

"Don't worry," I shouted. "You want some of these apples?"

"Nah," he yelled back without turning around. "I'll catch you next year."

Breaking Up and Starting Over

In a way, it felt unsatisfying that the paper I was holding was what made me the owner of the orchard. I looked through the pages, and there were words about land and plots but nothing about the trees. As I looked at them in their shadowy rows standing above me, I didn't feel like I owned them. Maybe it felt a little more like responsibility, which had come over me very gradually. I told myself it was what Mrs. Nelson wanted all along, if she was ever really serious about that "true heir" stuff.

That night I went over and told Amy and showed her the papers. She looked over them and then looked up

at me very proudly. "Well, how do you feel? This is just what you've been hoping for and tricking us all into."

"I don't know. Now that it's real, it feels a little weird."

"Have you told your other employees yet?"

"No, so please don't say anything. They've been bugging me non-stop about the money, but I've got to give it a few days to let it sink in and to make sure no one over there changes their minds." I gestured toward Mrs. Nelson's house. "I also have to figure out what I'm going to say."

***

It took all the way until the next Monday for me to get up the nerve to talk to the younger kids. I asked everyone, including Amy, to come to my room after dinner so we could discuss something important. They all sat on my floor expectantly while I sat on my bed.

"I just want to start by saying you all were better workers than I ever hoped for. If you didn't know it, I had no idea what I was doing and just kind of made things up as we went along," I said.

"Oh, we knew it," said Amy.

"Yeah, yeah. Well, if you remember how this whole thing got started, I was talking to Mrs. Nelson one day and she wanted to share the money that could be made from the orchard. But I left out some of the details that I have to tell you now."

"Oh, really?" said Lisa. "Isn't it a little late to be telling us now?"

Everyone stared at me with a mixture of fear and disgust. I went ahead with the whole story, including the trip to the lawyer's office, the envelope with the $8,000 in it, and then the conversation I had with Tommy. I held up the deed as a kind of proof of what I was saying. I told them how at first I had hoped to make a lot more than the $8,000 and planned to give all the extra to them. No one said a word the whole time. They just sat there with their mouths open. Michael was the first out of the gate with a response.

"How could you be so stupid?" he spit out, shaking his head. "That money was ours too. What makes you think you could just take it all and give it away without even asking us?"

"Yeah, we should have voted or something," said Lisa. "Except you knew we wouldn't have voted to do that."

I looked over at Amy for some support, but she just looked away.

"I know. I know I was stupid. It's just that I signed the agreement, and I was afraid she was going to take the money, anyway. And I'm sorry I didn't tell you the whole thing up front. I was afraid you wouldn't help, I guess," I said, trying to sound as sorry as possible.

"Yeah right, you're sorry," said Michael.

"Listen, since we agreed on percentages, if you want, you can own a percentage of the orchard."

"That's just a stupid piece of paper," said Michael. "We want the money."

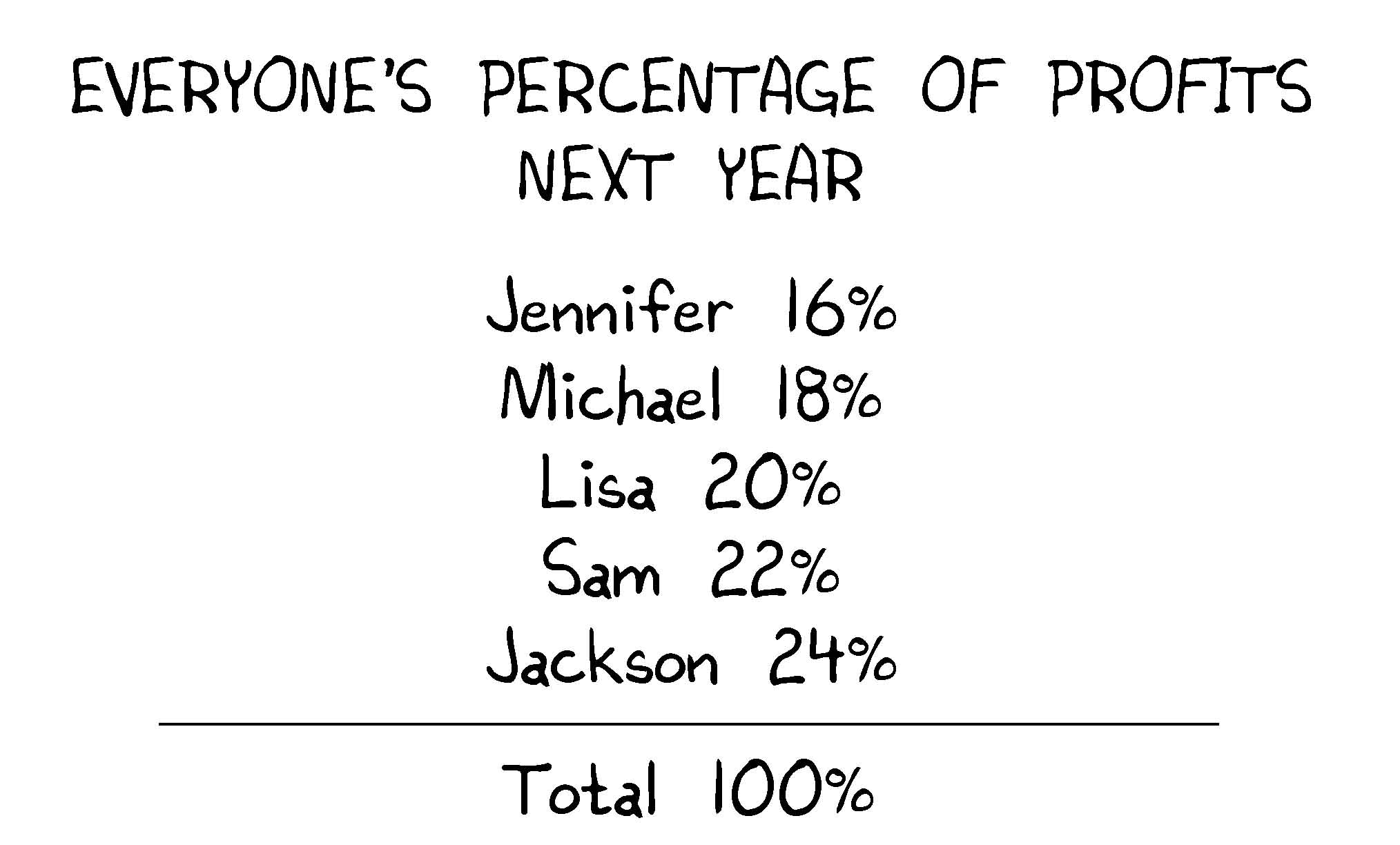

"Okay, how about this. Now that I'm the owner, we don't have to give any money to Mrs. Nelson on anything we earn in the future. What if next year you all get twice the percentages we agreed on this year?"

Lisa's eyes got big, and I realized I should have thought through the numbers before making the offer.

"You're trying to trick us again, aren't you?" said Michael angrily. He was looking back and forth between me and Lisa.

"Actually, that's a better deal than we had if we make the same amount of money next year," said Lisa in a calculating tone. "If we make $9,000 again and I get twenty percent, that's $1,800 for me. And over $1,600 for you, Michael."

"I want my money now. How are we supposed to trust him a year from now?" demanded Michael.

"We could put it in a contract and write it all up, just like Jackson had," interrupted Jennifer from the corner.

"Yeah, we can have a contract," I said carefully, still trying to add up percentages in my head. "Plus you all can split up the money that's left this year. I won't take any of it."

I brought out the remaining $646.30 and laid it out in front of them. The sight of the cash and the idea of the contract seemed to pacify them. They held a vote and it was unanimous in favor of the plan, although Michael kept pointing out that I could be tricking them again.

I also reminded everyone that we had done most of the hard work already. We could probably skip fertilizing the next year, the trees wouldn't need much pruning, and we could even try to hire Brother Brown's work crew for picking. They all seemed to agree, and I was amazed at how short their memories were.

I wrote out a contract right there in pen on a loose-leaf piece of paper. I tried to make it sound as official as possible by including words like "hereby" and "therefore."

Amy said she was "keeping her options open," so she didn't want to be a part of the contract. Everyone else signed their name on the paper. Lisa worked out the math and concluded that I would get 24 percent of next year's profits.

"Twenty-four percent? And he gets the orchard?" protested Michael.

"I'm the oldest. I'm supposed to get the most."

That reminder of our original logic stopped him grudgingly in his tracks.

"And I'm not going to take anything this year," I added.

"Let's give the contract to someone trustworthy to keep so Jackson can't change it," said Michael. "Amy, you better hold on to it."

"You know, though, you have to work hard or the agreement's off," I said.

"We aren't the ones I'd worry about," said Michael.

We split up the money after the contract signing. It wasn't really according to the percentages we had originally agreed on, but I figured it was close enough. I gave $200 to Amy, which she shoved instantly into her pocket. "I'm also going to give you some of my share next year," I said to her, "no matter if you help or not."

"I'll count on it," she replied with a laugh.

Sam got $142, Lisa $122, Michael $102, and Jennifer $80.30. I reminded them again that I wasn't keeping

anything for myself. Holding the money seemed to make them almost pleasant. Soon Lisa had convinced Sam and Jennifer that it wouldn't take much to set up a snow-cone stand next to the apple-selling operation, and she happily added up how much money she'd have by next year. I kept reminding her that her percentage of apple money was after expenses, which might include paying for some temporary pickers. Nothing I said slowed her runaway calculations.

When the meeting finally ended, I decided it had gone far better than I deserved. They had started off ready to kill me, and I ended up with a signed work contract for next year.

Amy spent all her money on new clothes the very next day, bringing home six bags crammed with jeans and shirts, doubling her wardrobe. Michael couldn't convince his mom to let him spend his money on pop, so I drove him down to General Supply so he could buy four cases of it. He hid them under his bed along with at least a hundred candy bars. He also bought three pocketknives and a half-dozen baby chicks before I convinced him he couldn't hold down anything more in the wagon without it flying off. Everyone else saved most of their money and, under Lisa's direction, opened savings accounts at the bank.

When I finally revealed the whole story to my parents,

my mom couldn't decide whether she was proud or angry. "Why didn't you tell us? I just don't understand it," she kept repeating.

Eventually parental pride won out, and she expressed it by baking about a dozen pies using the last apples I'd plucked from the trees. By the tenth pie, she'd perfected the recipe so that the warm crust and apple slices melted away in your mouth. I got as much as I wanted, plus ice cream on top.