The Year of Shadows (19 page)

Read The Year of Shadows Online

Authors: Claire Legrand

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Fairy Tales & Folklore, #General, #Social Issues, #Friendship, #Action & Adventure

“Cleaning,” I said, glaring at him.

The Maestro looked past me at his bedroom. “And what a cleaning job. Perhaps you will tell me the truth now?”

“I told you. Cleaning.”

“You shouldn’t go in people’s rooms without their permission, Olivia.” The Maestro wiped his face with a stained handkerchief. “I give you your privacy. You should give me mine.”

“That’s what you want, isn’t it? Your privacy. To be alone with your music. Well, you’ve got it now, don’t you?”

I couldn’t stop myself, even as I heard the words. Part of me screamed at myself to stop. The Maestro didn’t deserve my anger, my energy. I had more important things to do.

But the other part felt sick after all those letters.

Why didn’t you write me letters, Mom? Not even one?

Because of

him.

“I don’t know what she ever saw in you.” The sight of him repulsed me. He was too sweaty and too skinny and too tired. “No wonder she left.”

Something inside the Maestro snapped. I saw it in his eyes, like a light going out. He walked into his room and sank down onto his cot.

“No wonder,” the Maestro repeated. He stared at his piano. “Did you know, Olivia, that it is possible to fall out of love with someone? That people can love one another very much, and then stop loving each other somehow?”

I didn’t know what to say to this. The Maestro and I didn’t talk about love. That was always Mom’s thing.

“I loved Cara—your mother—very much,” the Maestro continued. “But that’s what happened. She fell out of love with me, Olivia. She fell out of love with our life together. And then she left us.”

I didn’t think mothers could fall out of love with their children. That’s what I wanted to say to him. But I couldn’t speak. I felt hopeless.

Then the Maestro’s face crumpled, and he started crying.

I told myself not to look directly at him. I started backing

toward the door. Then, when he buried his face in his hands and let out this awful gasping sound, I ran.

If I’d stayed there any longer, I would have ripped open that box and shoved the letters in his face and demanded an explanation. Either that or started crying right along with him, and that was unthinkable. The Maestro didn’t get to see me cry.

I ended up in the basement, not stopping to notice how weird it was for the door to be left open. Kepler never left the door open.

I found a switch and paced in the dim light until I caught my breath. Old instruments surrounded me. Boxes of worn curtains. Seat cushions chewed through by rats.

Nothing made sense anymore. Letters and kisses, dreams and sobbing Maestros and missing moms—it all whirled about in my head like a sketch left out in the rain. It whirled so hard that I didn’t see the hole in the floor until I’d already fallen through it, and I landed hard on my butt in the dirt.

“Ow.”

I squinted up at the hole in the floor. I wasn’t too far down, just a couple of feet. But it was still weird, for there to be this giant hole in the basement floor. The floor had been torn to shreds. I looked around and realized I was in a shallow tunnel that led back behind me into darkness.

The walls of the tunnel were grooved, like they had been dug away by someone’s fingers.

I started exploring, running my fingers along the grooves

in the wall. They were icy cold, and they left behind black grit on my fingers. I brushed my hand on my jeans to wipe off the grit, but it didn’t budge.

I looked closer. That wasn’t black grit. It was tiny speckled burns, freckling my fingertips. Wherever I had touched the wall, my fingers came away burnt.

Automatically, I clutched the burn on my arm, hidden beneath my jacket. I knew then that shades had been here. Maybe shades had even dug this tunnel.

I should have turned around and climbed out, but I didn’t.

A fat weight landed on my shoulder. Igor started hissing in my ear.

Must I constantly keep an eye on you?

Something crunched beneath my left shoe, and I ran face-first into a cold, hard wall of dirt.

Igor tumbled off my shoulder.

“What is all this?” I knelt down to examine the wall, which was packed full of brick, old wiring, and garbage. The corner of a piece of paper caught my eye. I couldn’t see anything on it but three letters:

“Urg.”

Igor, irritably cleaning himself, meowed.

I do beg your pardon?

“It says ‘urg’. Look.” I started digging into the wall. Mud caked beneath my fingernails. “It’s almost like whoever was digging here stopped all of a sudden.”

Igor wound himself between my legs, meowing louder.

“It’s the concerto.” I pulled out the paper as delicately

as I could. Twenty pages total, crumpled and filthy, but I could still read them. Frederick had written it in E major. How strange, to see his handwriting; it felt so personal. His real, nonghost hands had touched this. “Igor,

look

at it. Right here: It says Frederick van der Burg. We found it!”

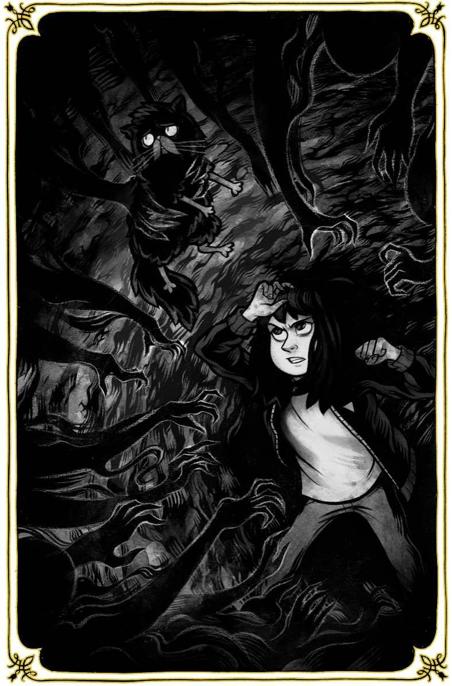

When I whirled around, grinning like an idiot, I saw four long, black arms spring out of the tunnel floor. Their fingers, five times the normal length, curled around Igor and started dragging him toward an opening in the tunnel wall. Past the opening was swirling blackness and crooked, shifting shapes.

Limbo.

I

CRAWLED TOWARD

Igor, screaming.

“Let go of him!” Too angry to be afraid, I pounded on the shades’ arms. Each thud burned my fists and sizzled like meat on a grill. But I didn’t care. They would

not

take Igor from me.

Cold wrapped around me as shadow-fingers brushed against my clothes. Caressed me.

Pet

me.

Then they let go, like

they’d

been burned. They dropped Igor and darted away from me, back into the opening in the tunnel wall. I’d never heard anything like the sounds they made—these awful wails that made my teeth hurt. Even as they slunk back into Limbo, they reached for me.

I staggered back, and they were gone. I was alone, clutching a freezing Igor to me. His coat was matted with frost.

“You’re okay, you weird, stupid cat,” I whispered.

Igor grumbled cattishly to himself.

I almost get killed, and you call me stupid?

Someone shouted my name: “Olivia!”

Henry jumped down into the tunnel and pulled me into a hug. The ghosts hovered right behind him near the tunnel’s entrance.

“You’re shaking so bad,” Henry said. “What happened? Are you okay? Should I call 9-1-1?”

I let him hold on to me for a few seconds before pushing him off. “I’m fine. Just a little burned.”

Henry whistled when he saw my fists, where I’d pounded on the shades. The sides of my hands were burned in twin black

C

shapes. “How will you hide those?”

“I don’t know. Gloves?”

“Yeah, because that won’t look weird.”

“What were you doing down here, Olivia?” Frederick asked sternly. He, Tillie, Jax, and Mr. Worthington were almost completely transparent. The tunnel walls shimmered through their rippling bodies.

“Are you guys gonna be okay?” I said, reaching for them.

“Please don’t touch, Olivia. We’re quite fragile at the moment.”

“That was Limbo, wasn’t it? That opening in the wall?”

They looked at where Limbo had been. Frederick sighed longingly. Tillie folded her arms around herself, like she was holding herself back from something. Jax turned away.

Mr. Worthington kept shaking. It sent chills through the air.

“Yes,” Frederick said. “That was Limbo. They were calling us to it.”

“Those rotten, stinking—” Tillie muttered.

“Dirty, lying—” Jax mumbled.

“Thankfully, they didn’t stick around with you and Henry close by, and we were able to . . . how shall I say it? Resist the temptation.”

Henry whispered, “We can almost see right through you, Frederick.”

“It takes a lot of effort to resist Limbo. One gets tired of fighting it, you see?” Frederick’s face wavered. “Now, what were you doing down here?”

“Oh, your concerto!” I grabbed the papers and held them up like a flag of victory. “I found it. Frederick, we have your anchor.”

Frederick’s eyes widened as he reached for the music. I held my breath, and Henry grabbed my arm. This was it: When Frederick touched his anchor, he would fade. He would move on, and it was happening too fast. I hadn’t prepared my good-bye, I didn’t know what to say.

Even Igor seemed to be holding his breath.

When Frederick’s fingers closed around the music, he straightened to his full height.

“But how are you touching it?” Henry whispered.

“Because it is my anchor.” Frederick smiled and stroked one smoky finger down the first page. “I think I am meant to touch it.”

I waited as long as I could stand it. “Why isn’t anything happening? You’re still here. Is it not working?”

“Henry, fetch me a violin, would you, please?” said Frederick calmly. “And then let’s all reconvene onstage.”

“Oh.” I watched Henry climb out the tunnel and felt suddenly tinier than Nonnie, tinier than anything. “You have to play it, don’t you?”

Frederick put his free hand through my shoulder. “Every anchor has a purpose, something it must do to be whole. What is music if no one ever hears it played?”

“Just some ink on a page,” I said dully.

Tillie floated in midair on her side, squinting at me. “You okay, Olivia?”

At the same time, Jax said, “What’s wrong, Olivia?”

“I’m fine.” Even though I wasn’t. First the Maestro crying, now Frederick leaving. Everything was happening so fast. I felt hollow inside, and tired. “Oh, and you spoke at the same time again.”

Tillie spun around in a little circle; Jax smiled. They always liked when I told them that.

I tucked Nonnie into bed while Henry and the ghosts made sure the Hall was clear. As usual, music bled out the Maestro’s closed bedroom door, rattling the walls. My mind automatically registered what it was: Mahler 2, again. At least he wouldn’t be able to hear us.

When Henry met us onstage with one of the old basement violins, Frederick’s fingers closed around it, just like a living person’s fingers would have. His wispy gray fingers became more solid. He brought the violin up to his shoulder and rested it there, under his chin. This hum started, like when a television’s on mute in another room, and the quiet electric buzz sizzles high up in your ears.

Too angry to be afraid, I pounded on the shades’ arms. Each thud burned my fists and sizzled like meat on a grill.

Frederick picked at the violin’s strings. Tiny

pizzicato

notes plunked into the air. Frederick slowly drew his bow across the violin’s strings.

A horrible, out-of-tune note

skrrritched.

“Well,” said Frederick sheepishly. “I’m a little out of practice, it would seem. Give me a moment.”

We gathered around the Maestro’s podium at the edge of the stage and waited while Frederick relearned the feel of the violin. Faintly, the memory of Frederick’s talent came back to me. The night we shared with him, his talent had settled in my brain. It had felt like when I held a charcoal and sketchpad in my hands; that was my talent, my violin.

“I wish we could hear it for real,” Henry whispered, scooting close to me. “You know, with a full orchestra. If I ever meet that Thomas guy in Death, I’ll have a thing or two to say to him, that’s for sure.”

I nodded. It was all I could do. If I opened my mouth, I would ask Frederick to stop, to stay, and that wasn’t fair.

After a few minutes, Frederick paused. “I want to thank you both. I don’t know what’s going to happen here, exactly, so I don’t know how much longer I’ll be with you.”

He smiled at me, the kindest smile I’d ever seen. So what if it was dripping and black and deformed, like a melting

jack-o-lantern? He was Frederick, my friend. And now he was about to leave, and I had to

hope

for him to leave, because that meant he would be safe and happy and wouldn’t have to fight Limbo anymore. What a horrible thing, to have to hope for your friend to leave you.

“But I hope you’ll remember me. I know I’ll remember you. If that’s even possible, in Death.” Drops of black smoke rolled down Frederick’s cheeks. “Goodness. I’m nervous all of a sudden. And I’m horrid at good-byes.”