Read The Yoga Store Murder Online

Authors: Dan Morse

The Yoga Store Murder (38 page)

Several key figures declined to be interviewed, most notably Brittany Norwood, as well as her family and her attorneys—just as they had declined all interviews from any reporters after the story broke. Their reasons were understandable: as of this writing, Brittany is still appealing her conviction. Neither she nor her supporters wanted to jeopardize that effort or bring more attention to the case. Instead, I studied letters her family members wrote to the presiding judge. I quoted every word Brittany spoke at her sentencing hearing, which remain her only public comments about the case. Most fruitfully, I read 11,000 text messages that Brittany sent and received from 2008 to 2011. These days, communiqués like these offer a direct view into not only what a person is probably doing, but also what she is likely thinking. To make the texts easier to read, I sometimes spelled out text shorthand, but never in a way to change the texts’ meaning. When Brittany texted a friend thanking her for setting up an interview for a fitness trainer job, for instance, she wrote, “I owe u big time,” which I changed to “I owe you big time.” I also interviewed as many of Brittany’s former friends, coworkers, coaches, and neighbors as I could.

I studied other written and electronic records, most of which have never been made public, including contemporaneous notes kept by detectives; audio and video recordings of law enforcement interviews with witnesses and suspects; evidence logs; diagrams sketched by crime-scene investigators; approximately 1,500 photographs from the investigation; 359 pages of analysis of citizen tips that poured in to detectives; and internal police reports summarizing all stages of the case. Montgomery County’s chief prosecutor, State’s Attorney John McCarthy, allowed me to read notes and outlines he wrote as he compiled his case and tried it in court. Donny Knepper, the defense attorney who served on the jury, also shared with me the journal he wrote at night and early in the morning as the trial took place. I reviewed my own notes from covering the trial, and read the 2,878-page official transcript of all the proceedings, which revealed conversations that had taken place out of earshot of the public and the jury. I also reviewed all the documents, electronic files, and physical evidence entered into the court record for the case. They included legal motions leading up to the trial; reports on DNA, blood spatter, and shoe prints; Jayna Murray’s autopsy report; 79 pages of Brittany Norwood’s medical records; and a brief psychological evaluation submitted for her sentencing hearing. I listened to tapes of the 911 calls, studied internal Apple Store video recordings, and watched and listened to more than six hours of interviews that detectives conducted with Brittany. I first learned about a piece of dialogue spoken by Jayna Murray—“We caught the bitch.”—from the reporting of Washington, D.C., journalist and writer Peter Ross Rauge, which I was able to confirm from sources. I learned about Jayna sending her brother, Hugh, a package to Iraq from the reporting of Erin Donaghue at Bethesda-Chevy Chase Patch, which I then spoke to Hugh about. I poked through boxes of physical evidence from the trial, still stored on shelves on the third floor of the Montgomery County Circuit Courthouse. I examined the red Buddha statue, the size-14 Reebok sneakers, and the black lululemon cap with the small bloodstain on the inside band, which had been found in the back of Jayna’s car. I lifted the bloodstained, metal merchandise peg, just as two of the jurors had during deliberations. At nearly a pound, with its sharp, flanged edge, the bar is a horrendously perfect weapon.

In the book, I tried to present this material as a narrative account of what characters said and thought as events unfolded. I was aided by detectives’ notes and, in certain cases, digital recordings. The investigators also testified under oath—during pretrial hearings and during the trial—about conversations that had taken place. From the witness stand, they recalled many of the most striking scenes of the case. Witnesses, like the Apple Store managers, also testified about what they said to each other during the events described.

Even so, much of the dialogue relies on people’s memories of what they said or what they heard, and readers would be well-served to remember that recollections are just that. When writing about a conversation, I tried to collect the memories of as many of the people present as possible, in some cases as many as five people who were in the room. When their memories of exact words differed, I presented the dialogue that best reflected the consensus. In hundreds of cases, I was able to use notes and reports to support when and where and how something was said. So when Detective Ruvin remembered the comments he made inside the police department’s evidence garage, I had reports from crime-scene investigators confirming that Ruvin was there at the moment he remembered saying, “Oh yeah, we got blood. We got blood.”

No one in this book read the entire manuscript before it was published. Nor was anyone promised they’d get a chance to review any sections. For the sake of accuracy, I showed key characters whom I interviewed sections in which they were quoted. I did this to check that I had accurately captured what they said or what they were thinking. No substantial changes or deletions resulted from this process.

A note about privacy. Cases such as this one inevitably drag the lives of private people into the public eye. In telling this story, I have delved into the lives of people who’d rather I had not done so—principally, Brittany Norwood’s family, friends, and roommates. I tried to make those names and materials public only when it added to an understanding of who Brittany Norwood was or what she did. In one case, I used a pseudonym—to protect the identity of Brittany’s roommate at the time of the murder. She spoke freely to detectives and prosecutors prior to the trial, even as her life was being turned upside down by the revelation that she had shared a roof with someone whom she, in retrospect, didn’t know at all.

I thank colleagues at the

Post

who encouraged me to step out from the comforting chaos of daily newspaper work to tackle this project, namely Greg Jaffe, Craig Timberg, Maria Glod, Mike Semel, and Vernon Loeb. Thanks also to those who read early drafts of my manuscript and offered valuable encouragement and criticism: Greg, Craig, and Maria, as well as Alison Howard, Dominic Preziosi, Pam Feigenbaum, Patrick Hickerson, Katherine Weymouth, Mike Wilson, and Stephen Merelman. My parents also weighed in on early drafts, including my dad, who was never less than candid: “This chapter was better than the one before it, which was kind of boring” was among his memorable reports. Thanks also to the fact-checking and research excellence of Jennifer Jenkins. The best reader of all was also the best part of my life, my wife and

Post

colleague Dana Hedgpeth. Another round of thanks are due to all of my family members who helped with so many home duties that I allowed to take a backseat to this project—Jet, Valerie, Lee, Margie, Morris, Emily, Mark, Nancy, David, Claire, and, again, Dana.

I also want to thank my agent, David Patterson at Foundry Literary + Media, who not only sold this book for me, but was essential in walking a first-time book writer through such a new and unfamiliar world. At Berkley Books, Shannon Jamieson Vazquez was the best kind of editor—someone who writes better than the author she is reading, and uses those skills to tighten, clarify, and simplify without changing meaning.

Jayna’s parents and brothers—David, Phyllis, Hugh, and Dirk—gave me almost endless time and insights, even when I asked the difficult questions. As the Murrays said from the beginning, they wanted me to learn as much as I could about their daughter and sister, flaws and all. Jayna wasn’t perfect, which to the Murrays made her all the more cherished.

Although the Norwoods chose not to speak with me, the family remains highly respected by those who do know them, and who shared their thoughts with me.

The accomplishments and demeanor of the members of both families—who all sat in the second row throughout the trial—were hardly lost on Judge Robert Greenberg. Moments before he sentenced Brittany, he looked at them and said, in a voice choked with emotion, “We don’t pick our families. But, frankly, if I had to pick a family, I’d want either the Norwoods or the Murrays.”

For years I have written about tragedies visited on parents. They always told me I’d never understand until I had kids myself. During the time I wrote this book, our first daughter approached her first birthday. I can’t pretend to know exactly how the Murrays or Norwoods feel, but I certainly understand it better.

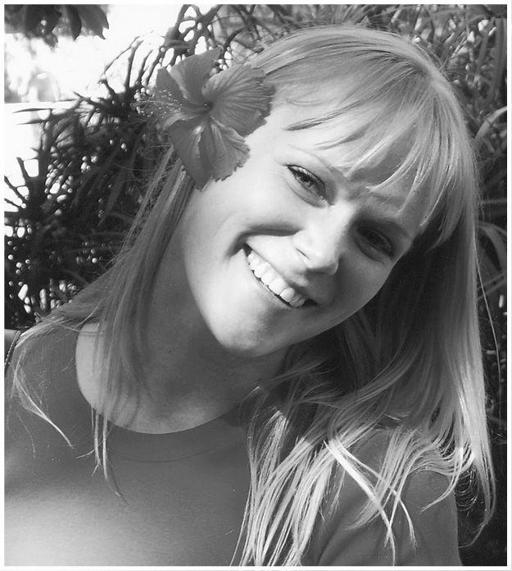

Jayna Murray’s smile lit up the room— or, in this case, part of the River Walk in San Antonio, Texas.

(Matt Deschner)

Both women worked inside the high-end lululemon athletica store in Bethesda, Maryland. No one could have guessed it would become a vicious crime scene.

(Montgomery County Circuit Court)

Brittany Norwood was quick with a beaming smile, even when posing for her driver’s license.

(Montgomery County State’s Attorney’s Office)

Signs of a struggle were evident in the back dressing room area.

(Montgomery County State’s Attorney’s Office)