There Was a Little Girl: The Real Story of My Mother and Me (47 page)

Read There Was a Little Girl: The Real Story of My Mother and Me Online

Authors: Brooke Shields

My mom was no longer occupying the space, and I did not know

where she had gone. All I knew was that I had to

leave

. I had to get out of that room.

I grabbed the doll, a tiny stamp-size photo of me as a baby in a sterling-silver heart frame that was by the bed, and my purse and opened the emergency door. The buzzer always buzzed while the door was open and I had gotten used to it. Today, however, it seemed suddenly extra loud and long. I ran into one of the downstairs offices, half-thinking she’d be right behind me and I was busting her free from a cell. I brought with me a charger I had borrowed. If only I had thought to bring the charger down a little earlier, Mom would have waited longer to die. I was sure of it. That was the thing I needed to do to keep Mom alive. I tried to explain to the staff that I just had to return their charger. I just had to. I was never coming back there again to do it. “Here is your charger. Thank you.” I knew when I turned to leave that I would not be back. I ran out to Eightieth Street and turned west toward First Avenue.

I got to the corner and stopped, not sure what to do next. I needed to get back to some place. I remember feeling like this on 9/11. I ran out of my apartment on Fiftieth Street and just started speed-walking up First Avenue. That day, like today, I had no idea where I was headed. Some taxis had begun to run again but I was suddenly afraid to get into one. Chris was in LA and not picking up his phone. I left him a message about my mom and just began pacing in a small radius on the southeast corner of Eightieth Street and First Avenue.

As I was looking up and down the avenue, a beautiful foreign girl was crossing the street in front of me. She may have been from Brazil or Spain—I couldn’t tell—but she was very pretty, except for the cigarette that was hanging from her red-lipped mouth. As she passed, she recognized me and started excitedly to try to talk to me about “

Laguna Blu

.” I began to feel like I’d black out right there. I think I said thank you and that she had pretty hair and then I tried to look away.

She was staring at me with a kind, questioning look. She asked if I was OK. I blurted out to her that I was not OK and that my mom had just died. Could I have one of her cigarettes? I do not smoke. I have never been a smoker. The times I have been drinking and have tried to join in, I felt incredibly and uselessly sick. But in this moment I wanted to feel that sick sensation even just to know that I was in fact still alive. I wanted to fill my body with disgusting smoke and nicotine and get that head rush and feel the sweating that precedes vomiting. She gave me one and went on her way after trying to say something sweet in broken English. I took two drags on the cancer stick and threw it out. I was alone on the street again and had no idea where to turn.

I did not look for a cab but instead went inside a kosher meat market on that block. Standing by the refrigerated items, I called my friend Stephanie and asked if she’d come meet me here because I needed to go home and cook steaks. I was crying and saying how horrible it was to see what I had just seen and that I was afraid to be alone.

She said she’d meet me ASAP and told me to hold it together. An old couple was buying some meat nearby and had obviously heard me on the phone. I had not tried to be discreet. In fact, I believe I had purposely talked loud enough to not be alone. I knew they, too, had recognized me, and I secretly hoped that if they knew I was sad, they would say something wise to offer me comfort. It is amazing to me the comfort of strangers in moments of dire straits.

I was beginning to have the feeling I used to get as a teenager when I felt like I was disappearing. It usually happened in large crowds and I believed that if I screamed, nobody would hear me. I caught their eyes and tried to smile. Maybe they would understand my fear and pain. The old man nodded and said, “We know who you are.” The woman then chimed in with some type of “circle of life” comment and I instantly hated them. I was so jealous of their old age

and their seeming happiness and of the fact that they had one another. How could they know what my mom felt or how I was doing? How dare they try to help me? Who did they think they were? Fuck them!

I nodded, bought my meat, and went to wait on the street. I started to beat myself up for talking loudly on the phone and for looking to strangers for recognition of my pain. It was an affliction of mine of which I thought I had been cured and felt angry to have seen it rear its ugly head once again. Thankfully, Steph got to me and we drove downtown together. By the time we arrived at the house, Lisa was already there. She knew something was going to happen and cleared her day. I must have called her to tell her but did not remember much from the previous hour. Chris got me on my cell and I told him I couldn’t talk because the girls were with me and if I stayed on the phone all I would be able to do was cry, hearing his voice. My mom loved Lisa and Stephanie like her own daughters and they knew her better than any of my friends. It made perfect sense to have us all together.

Another friend from our school arrived as well. I must have called her, too. I don’t remember calling anybody but Stephanie. All I remember from the rest of the day and night was a big fire in the living room, steaks on the grill, and lots of wine. We managed some morbid humor so as to keep me from careening off a cliff.

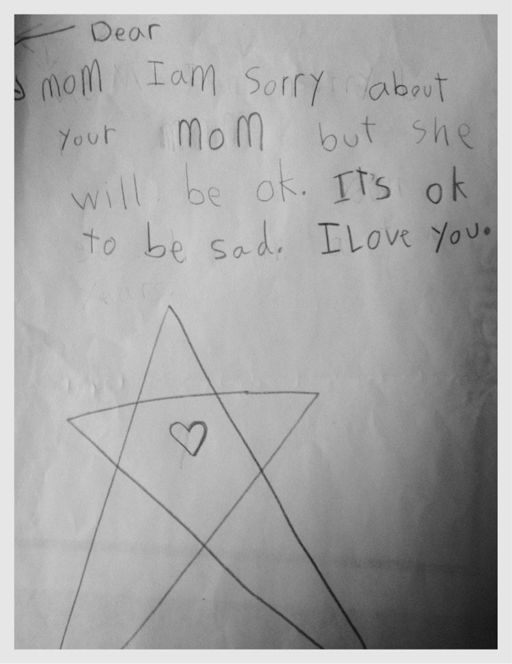

Overall, I was numb. I was not tired but I knew I could not handle being awake much longer. Being awake was simply too dangerous. I was offered a sleeping pill but was terrified that I would have some kind of hallucination and not make it through the night. Some more wine seemed to do the trick, and I promised my friends it was safe for them to leave. My girls came home from a friend’s house and let me sleep. Chris must have told the girls about their Toots. In the morning I opened my door to find a note from Grier that read, “Dear Mom I am sorry about your mom but she will be OK. It’s OK to be

sad. . . . I love you. . . .” She had erased something under the “I love you.” “You will see her soon. . . .” I cried at how sweet the note was and then burst into hysterics at the part she erased.

It was October 31. The day that Hurricane Sandy dissipated, Mom dissipated, too.

Chapter Nineteen

Cremation/Look, Ma, No Pants!

T

he funeral home came and took Mom’s body. I had gone there a few weeks prior to make all the arrangements. The funeral director had told me to also contact the church ahead of time, which I did. Afterward I even stopped at Finnegans Wake for a cold beer after speaking to the priest. It was a mini-tribute. One of Mom’s old haunts when we lived on Seventy-Third Street. It was easiest to find her there because it was often the first stop and was just at the end of our block. I didn’t even have to cross the street.

My assistant Mike had flown in from LA to help me prepare for the memorial. In the two days that he had been in New York City I suddenly decided to have him go through all my closets with me. We did a massive frenzy of a purge. I needed to stay busy because I was afraid to feel. I could not stop myself from whipping around my house and cleaning it all out. I combined my stuff with my mother’s from the residence and we lugged four grossly heavy black garbage bags into our car. Mike had finally found gas, from a Hasidic Jewish man who had a minipump under a bridge in Brooklyn. It was surreal but

Mike followed up on a tip from a buddy and we had wheels to get to the Upper East Side funeral home. Mom had a favorite thrift store that had been around for decades. It was the same one in which she bought her Puccis and my infamous gauchos.

Parking was hard and we could only find a spot five blocks away. Sweating and running, we lugged the bags across middles of streets and finally reached the store. I deposited the mother lode, and the little ladies behind the counter were thrilled. They recognized me but, when they heard my mother had died, did not ask for a picture. I explained it was my mother’s stuff as well as mine and she had died two days prior. I needed to keep saying it to believe it was actually real. I joked to Mike that I should have said “the mother loaded,” because Mom would have thought it funny and a bit outrageous. We rushed home because we still had no power and the house was empty and without an alarm.

The funeral director called and explained to me that they were going to use a different facility for cremation because their regular one had lost power due to the storm. I told him Mom would prefer the one without the power! I think he got the joke but was afraid to laugh. Funeral homes make me laugh nervously. Otherwise it is all just too horrible.

They had taken Mom’s body to be embalmed so I could view her and say good-bye. Two days later I was called and told she was ready for me to see. I was first shown the vessels to choose from for after cremation but was unhappy with the choices so I said I would buy my own.

I was then sent up to the ice-cold viewing room. It was huge and empty except for Mom’s basic wooden coffin at the far end. They said they have to keep the room cold because if not the bodies thaw. A detail I did not need to know. He closed the door and I stood for a moment before moving. I then walked across the huge empty room and it felt like an hour-long trip. There she was in her shitty stiff cotton leopard-and-neon-printed shirt and nothing on the bottom. I looked.

Under the cover was just a plastic tarp and I did not see her big grandma panties, either. I did not inspect too closely for obvious reasons but I had to know about the stuff they don’t show you. It did strike me as morbidly funny and knew that Mom would get a chuckle out of it all as well.

“Look, Ma, no pants!” I said. “Oh, Mom . . . here we go. Haven’t you taken this far enough? You are not getting up, are you? I love you, you know that, right? God damn it, Mom. Really? We could have had more laughs. My babies are really funny, too. I am sorry.”

And with that, I put the weird square-bodied doll in the box with her and placed my picture in the little heart frame, which by the way was one of the party favors from my sweet-sixteen birthday. Mom had over two hundred made with a picture of me as a baby inside. We would always find the extras hidden in surprising places. I tried to put the small frame in her now freezing hands but once again could not open her fingers because this time she was actually dead and stiff. I attempted to wedge it under the clasped part but it felt too Sopranos-like. I settled on placing it on her sunken chest and pictured it rolling off during her transfer to the crematorium facility in Long Island City.

I had to kiss her forehead, which was indeed freezing and such a contrast to the moments right after her death. I am glad I did it, but wish I had not. My lips will forever remember the cold, smooth skin. She still didn’t jump up or tell me it was all OK. And it wasn’t OK. None of it had been but here we were. This was indeed it. The moment I had been afraid of my whole life.

“I love you, Mama. Bye.”

I walked out, looking back once more and wanting to rush in and shake her. I was so truly alone. And she was so not ready to go.

I was quiet in the car as we drove away.

Three days later I got another call from the funeral director. He was hemming and hawing and I could tell something was wrong.

“Yeah . . . hi. . . . Well, you know how I said that we were using a different facility to do your mother’s cremation?”

“Yes?”

“Well . . . yeah. . . . OK, well . . . we um, we started the process. . . .”

“Yeah?”

“And then, um, well, that facility lost power as well. So we had to then have your mom sent to a different one.”

“OK . . . So was she . . . ah, lumpy . . . or just done from the waist down, or . . . You know what,

don’t

tell me. I don’t need to know. . . . I am good. . . . Thank you.”

I went shopping at antique stores for a sterling-silver container of some kind. I even toyed with the idea of its being a martini shaker as an inside joke. I could not find one big enough. Neither did my mother, obviously!

Anyway, I ended up buying a sterling-silver round jar with a lid that probably had been used for biscuits or cookies. It must have been some kind of retirement gift because it had engraving in a foreign language and a date around the lip of the lid and was very heavy. My plan was to put her on my bar and nestle her among the array of glass bottles and sterling knickknacks and stirrers. I figured this way she could remain forever close to the two most important things in her life: me and booze.