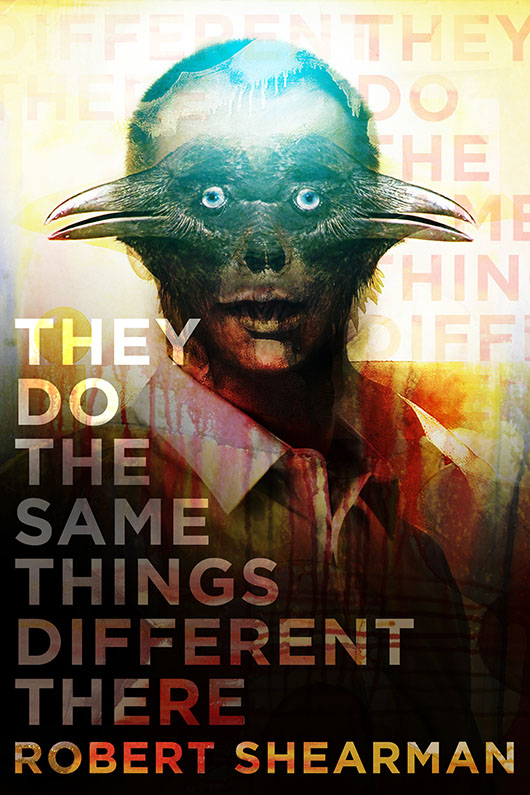

They Do the Same Things Different There

Read They Do the Same Things Different There Online

Authors: Robert Shearman

ChiZine Publications

Robert Shearman

“Thrillingly unpredictable, bizarrely life-enhancing. . . . Shearman is a great writer.”

—

The Scotsman

“A writer who is not afraid to approach the big subjects, but does so from interesting oblique angles and with a light, kittenish gait. Rather profound, ingeniously plotted.”

—

The Independent

“Shearman’s prose is a mixture of faux-naive mundanity and breathtaking fantasy visions. Addictive. Wonderful.”

—

SFX

“Corrosively funny, wistful, sharp, strange and black as a coffin lid, Robert Shearman is an addictive delight.”

—Mark Gatiss, Co-creator of

Sherlock

“Shearman offers us haunting, nightmare alternatives to our world that are still somehow utterly recognizable as our own, thanks to the way he always picks out the comically mundane among the impossible and the fantastical.”

—Steven Moffat, Executive Producer and Hugo Award-winning writer for

Doctor Who

“His stories are like the bastard offspring of Philip K. Dick and Jonathan Carroll, but with a quirky personality that is completely their own.”

—Stephen Jones, World Fantasy Award-winning editor of

Best New Horror

“Shearman has a uniquely engaging narrative voice and he steers clear of genre clichés, injecting elements of horror and the surreal into a recognizably real world. As impressive as his quirky imagination is his emotional range: most of the stories are darkly humorous, but humour, horror and genuine pathos all make a powerful impact in a very short space.”

—

The Times Literary Supplement

“Shearman’s stories are hard to categorize, a unique fusion of literary and the fantastic, perhaps not surprising from a writer whose credits include

Doctor Who

scripts and mainstream theatre.”

—

The Guardian

Robert Shearman

Remember Why You Fear Me:

The Best Dark Fiction of Robert Shearman

Everyone’s Just So So Special

Love Songs for the Shy and Cynical

Tiny Deaths

Other Books By Robert Shearman

That Tiny Flutter of the Heart I Used to Call Love

Sounding Brass Tinkling Cymbal

It’s not that they thought it wasn’t worth reporting, it was just a matter of deciding where to schedule it. It wasn’t a human interest story, after all, and it wasn’t an issue of national concern, how could this possibly affect the average British voter? And global importance, well, no, clearly not. It was something quirky, something a little whimsical, a story that would amuse rather than educate, distract rather than inform. And that’s why the disappearance of Luxembourg didn’t headline the news, but was announced instead somewhere just between the sports round-up and the weather.

It wasn’t even as if anyone could ascertain for how long it had been missing. It’s not like Luxembourg was a country people were in the habit of looking at. A housewife in Belgium said that on Wednesday she’d thought to pop across the border, go to this grocery store she knew, the milk was always cheaper there. When she found out there was no longer a Luxembourg to pop across to, nothing but water stretching off as far as the eye could see, she’d turned right round and bought her goods from the supermarket in Antwerp. She said she might end up paying a bit more, but at least they were

reliable

. And no, she hadn’t bothered to report the missing nation for a couple of days. When asked why, she said she was always mislaying things, there was no point in making a fuss, they usually showed up again sooner or later.

Juliet had never been to Luxembourg. Colin had. Sometimes she’d ask him what it was like there. “Oh, you know,” he’d say vaguely, and shrug. And she’d smile, and nod, and change the subject, but she didn’t know, that was the whole point, why else would she be asking? Sometimes he’d be a bit more forthcoming. “It’s got nice architecture,” he’d say. “Yeah, some of the architecture is quite nice. Quite European.” Juliet didn’t know Europe very well. She’d been on a day trip to Dieppe as a schoolgirl, and there’d been that summer holiday near that beach in Tenerife. Both times it had rained. She’d asked whether one day she might go to Luxembourg with him. She still had her passport, look. And showed him the photo of her inside, with that bemused expression on her face as the flash caught her by surprise. And he’d laughed, and said, no-one

chooses

to go to Luxembourg. He’d find them somewhere better than Luxembourg, just wait and see! Maybe on their anniversary. But the anniversaries had come, and then gone, several of them now, and that photo of her in the passport was looking terribly young now, she wasn’t sure the customs people would let her through.

When Juliet saw the news story, she felt the urge to call out for Colin, she thought he’d find it interesting. But then she remembered. He was on one of those business trips of his, in Luxembourg, he did a lot of business in Luxembourg these days. Even at that very moment she thought he’d be enjoying himself, sampling the drizzly weather and the architecture. She settled down to watch the whole program, stupidly she half wondered whether Colin would get a mention. But they didn’t talk about Luxembourg for long, soon it was time for

EastEnders

. So she watched

EastEnders

instead. She supposed there was nothing to worry about. She supposed if there was something she ought to be doing, someone would soon tell her to do it.

The next morning Juliet got up early, watched the news before going to work. She was a bit sleepy, so may not have been concentrating hard enough, but she was pretty sure Luxembourg wasn’t mentioned at all. She asked the other girls at the supermarket about it, but none of them knew what she was talking about. Mrs. Wilson, who was deputy manager, but also did turns on the pâtisserie counter, so wasn’t as big a deal as she thought she was, said she’d heard

something

about a country disappearing, but was certain it was Liechtenstein. And that gave Juliet some hope, she didn’t think even Colin had visited Liechtenstein, she might still have a husband after all—but that night she watched the evening news, and there was an item about it, just a very short item, and it

had

been Luxembourg the whole time. “Country still missing,” said the report. “Experts baffled.” They had a financial boffin in, to work out how much the nation’s absence would affect share prices and the FTSE—and he concluded it wouldn’t make the slightest difference. And there was an editorial about it in

The Sun

, in an article entitled “Luxem-gone!” neither the title nor the contents of which made any sense whatsoever.

All that could be said with any certainty was that a nation of some half a million souls had been yanked out of existence. Fifty miles long by thirty-five miles wide, it was as if one of the jagged jigsaw pieces that made up Europe had simply been taken from the puzzle by its cosmic player. Not that many alluded to this being the handiwork of God—it was all very well some tub-thumpers claiming it was divine retribution for the evils that Luxembourg stood for, but since no one could work out what Luxembourg’s stance had been on

anything

, it wasn’t very convincing. A few theories did the rounds. Some said it was because of continental drift. It was unusual, admittedly, for a landlocked country to be drifting, but just because it had never happened before didn’t mean it hadn’t happened now. Others blamed it on global warming. They suggested that perhaps Luxembourg had been using a higher than average number of aerosol deodorants or CFC-bearing fridges per capita, and if someone could only conduct a few surveys on the ecological habits of the Luxembourg populace, they could prove it. It was hardly their fault, they said a trifle defensively, if there was no Luxembourg populace left to survey.

But the sad truth is that there weren’t

that

many theories, because there wasn’t that much interest. It had only been Luxembourg, after all. For a few days the nations of the world waited to see if anyone else would vanish—and when no one did, they heaved a sigh of relief. And, it must be said, looked at their neighbours sideways on, and felt a twinge of disappointment too.

The only remaining flicker of interest was not in Luxembourg itself, but what had been created in its absence. Small as a country it may have been, but the gaping puddle it left behind was considered to be rather on the large side. France called it “La Manchette.” Belgium called it “La Mer Belgique.” The Germans went one better, gave it the name “Fehlenderangrenzenderlandsee”—if anyone referred to it as something else, they put their fingers in their collective ears and pretended not to understand. There were quite heated discussions between the three countries, and even hints that all or any of them might be prepared to go to war to claim this fresh territory. And then the USA stepped in and said they were all being very silly—if they were going to behave like children, none of them could have it, so there. So it was named The American Channel. Everyone seemed satisfied with that. And with this last matter solved, Luxembourg dropped off the world’s radar again, and every nation on the planet could get back to what it had been doing in the first place.

Juliet didn’t find that so easy. Colin may have been away on his business trips rather a lot, but her life still had revolved around him—if not his direct presence, then at least anticipation of his weekend returns. The weekend had always been about Colin, he ran through it like lettering through a stick of rock. On Saturday they would go out and do the shopping, and that night they’d curl up on the sofa and watch a DVD. If the movie wasn’t too long, or if Colin wasn’t interested in the special features, afterwards they might make love. That first Saturday she’d still half expected him to turn up; the night before she had, as always, vacuumed the house from top to bottom. Not that he ever commented, but she knew he’d notice if she didn’t bother, she wanted the house to be just perfect for the time he was there. She adapted quite well, considering—she just pretended it was a Thursday instead, a Thursday without work, a long Thursday evening maybe, and carried on as normal, she was quite used to being on her own. But come the second weekend she found it all quite frustrating. She didn’t know how much food she should buy on the shopping run, and the DVDs weren’t nearly so much fun without Colin talking through the whole thing. She looked at the house, all newly cleaned, and wondered why she’d bothered. She began to fixate on his absence. It became a solid thing, somehow; she didn’t know that absence could take up space, but it did—Colin wasn’t there when she got up in the morning, Colin wasn’t there when she went to bed, and he insisted on not being there at any time intervening—in a strange way, his very absence filled the house more completely than his presence ever had. She supposed she mentioned Luxembourg quite a lot at work, rather too much even. Mrs. Wilson took her to one side and told her to stop going on about it, she was boring everyone to bloody death, and since Mrs. Wilson was speaking to her at that moment in her capacity as deputy manager and wasn’t even in spitting distance of the pâtisserie department, Juliet supposed she’d have to listen. And that seemed fair enough, she was beginning to bore herself too. And on the third Saturday in a row, as she lay there in bed, on her own, indisputably on her own, and there was no love making to be had, not even a sniff of it, Juliet told herself it was high time she did something about it all.

She supposed there must be many people out there who’d lost family when Luxembourg vanished—but since the overwhelming majority of them had been in Luxembourg too, there was no one she could compare notes with. She decided that Colin was dead. Once she put it like that, without fanfare, without qualification, everything seemed so much simpler. And seeing that he was dead, she decided too that she really ought to be grieving, that’s what was called for at times like these. She stood in the bathroom, looked at herself in the mirror, practised expressions of sorrow and loss. It was hard work. In truth, she

did

feel sad, but, thinking about it, she felt sad pretty much most of the time, she wasn’t sure Colin’s death had very much to do with it. She had hoped that being sad already would be a help, that it wouldn’t take much of a leap to get from her normal state of faded ennui to an appropriate display of grief. But just when she thought she’d got a handle on that grief, that it was finally taking shape, she’d lose her concentration and slip back into her usual sadness again. And wonder afterwards whether she’d been kidding herself, what she’d begun to feel wasn’t anything like grief, not even in the same ballpark, it was just hunger or tiredness or boredom. Juliet had no experience of mourning, didn’t know what it was she was reaching for. She’d never lost anyone; her siblings, her aunts and uncles, they were all still about, all still kicking. Her parents had stayed stubbornly alive—they were getting on a bit, and Juliet couldn’t see what they actually

did

with all that life, but they were there anyway, if not exactly energetic, still nowhere yet near death’s door. She’d have to try to mourn a bit harder, really put her back into it, she stared at herself in that mirror of hers, she practically

gurned

with the effort. She tried to visualize Colin as a corpse. But it was no good, he always just looked asleep, it made her drowsy just to think of him, it made her want to get into bed beside him and cuddle. And if she tried to imagine him with his eyes open, the facial contortions she put him through to make him look sufficiently deceased just gave her the giggles.

Colin’s family felt sorry for Juliet, of course. They’d never much liked her, this shy girl that Colin had married so suddenly, pretty but not quite pretty enough, always hanging in the background at social occasions, never speaking unless she was spoken to and not speaking anything of interest even then, always too eager to pass the phone straight to Colin without saying more than the quickest of hellos. But they didn’t dislike her either; there was nothing to dislike. They could quite appreciate the awkwardness that Colin’s disappearance must be putting her through, and even if their sympathies had not yet been conveyed via greeting card or phone call—they wouldn’t want to interfere—they were genuine enough. But when she invited them to Colin’s funeral, they were somewhat irked. “He’s not been in Luxembourg a month!” his mother told her. “Some people go on

holiday

longer than that!” She went on to tell her, in no uncertain terms, that there was no body, so he couldn’t legally be pronounced dead, and even if there

were

a body, it would barely have cooled yet, what was her bloody rush? And Juliet told her quietly that she needed to move on. It was time. She had to move on. And although Colin’s mother might have thought that Juliet was a brazen slut, that she obviously had some new man already lined up to take Colin’s place, that she’d probably

wanted

Colin dead, yes, actually

wanted

it, so she could cop off with the nearest feller, that really wasn’t it at all. Juliet just didn’t feel she could accept Colin had left her until there was something official to tell her so. She asked the vicar if there could be a service at the church—no, there was no body, not yet, but she thought Colin’d have preferred cremation if that was any use—and was told that, sorry as he was for her loss, it wasn’t quite a loss big enough for him to help her with. So the funeral became a wake, held at her house that Sunday, and all Colin’s family and friends could come and pay their respects if they wanted to. Not many did. She’d been out on the shopping run the day before, had massively overcompensated on the sausage rolls and the scotch eggs, she’d be picking her way through them for months.

As she was washing up in the kitchen, Dave came in and asked if he could help. Dave said that she was the widow, she shouldn’t be doing all the work. And Juliet said he could do the drying if he liked, there was a towel hanging by the saucepans. Juliet liked the sound of “widow,” it gave her a buzz, and all day long she’d been waiting to feel something. Dave was three years younger than Colin, and would look a bit like him too, if only his hair were greyer and he were a bit fatter and he wore glasses. He’d come up from Leatherhead with his wife Sheila and their four-year-old son Tim, who’d been running around the house all afternoon pretending to be a dinosaur and who was clearly not making any better a stab at this grieving thing than Juliet was. “Do you miss your brother?” she asked Dave, as she handed him a cake knife.