Things to Make and Mend (20 page)

Read Things to Make and Mend Online

Authors: Ruth Thomas

But the flowers are not from John or Pearl. There is a note that says: âCongratulations, Big Shot! With love from the

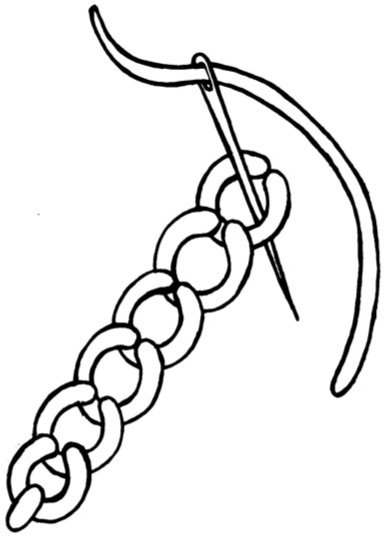

Needlepoint

Sisters â xx'.

My friends.

The balloon bobs like a speech bubble above her head.

*

Sitting on the bed again, she gets the phone out of her handbag, switches it on and dials directory enquiries.

A girl answers. âWhich town please?'

She holds the phone close to her ear and reaches for the courtesy notebook from the bedside table. She lowers her voice. âEast

Grinstead,'

she says. âI'm looking for a Second Glance in East Grinstead.'

âA second glance?'

âIt's a dress agency.'

âAn estate agency?'

âNo. A dress agency'

âA dress agency? What's that?'

âIt's like an estate agent's, except it deals with dresses.'

There is a small silence at the other end of the line.

âI've got a Second Glance on the High Street, East Grinstead. Will that do? Shall I put you straight through?'

âYes, that's the â'

There is already an automated voice telling her what the

number

is. She jots it down in the notebook, hesitates, then dials.

âYes,' the agency woman in the polo-neck jumper informs her, âyes, I was going to phone you later. Because we've just sold your dress. We sold it yesterday in fact. I thought it would go quickly, because it was a pretty dress. Such a pretty colour. Would you like me to send you a cheque or will you come in to collect it?'

âIf you could send me a cheque,' Sally replies.

How easy, how easy it is, sometimes, to let things go. Material things. Bye bye, dress. She wonders what she will spend the money on. A pet-hair de-fluffer? A bra organiser? Or, no: something Rowena would have liked. It is the only way she can apologise.

*

Before phoning Pearl she sits for a few minutes beneath the

bobbing

balloon. It has a little sandbag tied to the end of its string, to weigh it down.

âSo how did your talk thingy go?' Pearl asks.

âIt went pretty well.' She leans against the bed's headboard and flicks over the hem of a pillowcase to examine the stitches: a habit formed years ago.

âSo. It was funny,' she says, not wanting to broach the subject of the young man in the café. âMy old Needlework teacher was at the conference.'

âHow bizarre.'

âYeah. It was. It was â¦' She tries to think of the best word to describe their encounter. But thinking about its implications is a little terrifying.

â⦠revealing,' she says to Pearl. âA blast from the past.'

âA what?'

âIt was just quite strange.'

She doesn't know what on earth to say to Pearl about the young man in the café. Where would she start, without feeling hypocritical? She imagines her daughter standing in John's kitchen, fiddling with the little piles of domestic jetsam and

flotsam

that always end up there. Biros. Rubber bands. Bits of flux. Corners of envelopes with unfranked stamps. Maybe she is in love with this boy. Maybe everything she sees is altered because she is in love.

âGuess what?' Pearl says.

âWhat?'

âEmbroidery Times

came today.'

âDid it?'

âGuess what they've got in the “makes” section?'

âI can't imagine.'

â“Embroider your own cafetière cover.”'

âNo!'

âAnd,' Pearl adds, “Embroider a sleeping bag for your pet hamster.”'

âYou made that one up!'

âNo I didn't!'

There is the sound of a door opening in the corridor outside, two voices speaking, a man's and a woman's. The rumble of a wheeled suitcase. Then the door closes again.

âMum?'

âYes?'

âYou know that vase I broke?'

She thinks for a moment. âYes.'

âWell, it's OK. It's just, it was â¦'

Sally looks up at the balloon moving in the breeze from the open window.

âSweetheart,' she says, âIt's not a disaster. People break things. Things can be mended. That's the beauty of inanimate objects.'

She clears her throat and feels motherish. She pictures herself progressing into her future â walking, wisely, motherishly, on to the plane.

âIt's just, I broke your sewing machine too,' says Pearl.

âOh.'

âIt kind of fell off your table. I was looking for your pinking shears in those little drawers and it kind of â'

âMy pinking shears?'

Still with the phone at her ear, Sally bends and attempts to pick up her portfolio and her handbag. She nudges her rucksack with her left foot. She looks at the flowers and the balloon.

Do they allow balloons on planes?

âWhat did you want my pinking shears for?' she asks.

âTo cut someone's hair.'

âSomeone's hair? With pinking shears? Whose hair?'

âLiam's,' Pearl replies, almost inaudibly. âYou know, that guy you spoke to yesterday? He's kind of ⦠I was going to tell you before but you went up to Scotland and everything â¦'

Sally gives up on the balloon and lets it rise in front of her again, tugging at its own weight.

âIt was for a fancy dress party,' Pearl is saying. âHe went as a tetrahedron. I went as a circle. He's going to get it cut out. It's, like â¦'

Well done,

says the balloon.

âSweetheart, I've got to go now or I'll miss the plane,' Sally says. âI'll have a look at the sewing machine when I get back. It's

pretty resilient. And it doesn't really matter. It ⦠You know, the main thing is â¦'

And she looks up at the balloon and wants to say something to her daughter about the young man. About being with people who make you happy. That is really all she wanted to say.

Into her head comes a picture of two girls, best friends,

roaming

around some basement shoe shop full of teenage footwear. Laughing, one of them picks up a tasselled platform boot.

The words on the badge Sally Tuttle once gave me were

so

tiny that you had to get really close to read them.

‘What are you staring at?’

An example of irony.

I pinned it to my school scarf the day Sally gave it to me. Then I lost the scarf, with the badge on it, a few weeks later. And I always felt strangely guilty about it. It seemed a bigger thing to have lost than it was. Sometimes, in the later stages of my pregnancy, I thought about that scarf and that badge. I wished I could have pinned the badge to my jumper, right over the bump.

Sally used to stare at me too, then; I could sense her staring in disbelief across the playground. She appeared to have formed some alarmingly hostile opinion about me. Maybe she’d had some attack of morality. Or some strange kind of jealousy. Whatever, she no longer spoke to me. And I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know how to tell her how it had happened. A teenage kiss that had progressed, altered, turned into something else. Very quick, very easy. It had not even been the romantic event I had been led to believe. But I had still ended up pregnant.

Pregnancy had been something Sally and I

joked about.

‘Never say

Ich bin satt

to a German person,’ Sally once informed me after one of her swiftly abandoned German lessons. ‘It doesn’t mean I’m full, it means I’m pregnant!’

Our conversations had been like the ones in bubbles in

Jackie

magazines. (

‘D’you think he loves me, Rowena? I’m not sure if he loves me …’

)

Neither of us had talked about the practicalities of love. We had not considered that love was bound up with practicalities.

*

Kenneth and I are late arriving at the airport and have to hurry to the check-in desk. We trot, pulling our suitcases behind us. We jog past other travellers, all looking tired and wide-eyed, as if they have just been jolted awake in the middle of the night. And we have nearly made it – there is the British Airways sign and the queue – when my ankle suddenly twists and I find I am falling, all my belongings clattering about me.

There is a tiny pause, a snag in the smooth fabric of our airport surroundings.

Kenneth says, ‘What are you doing?’

‘Well, I’ve just fallen over,’ I retort. The floor tiles are hard and glittery. All around us there is the sound of trundling luggage and clicking shoes. People walking past stare; some even look back over their shoulders at this floored woman, who appears to have knocked over a yellow plastic cone which says ‘Caution! Wet Surface! Trailing Cables!’

‘You OK?’

‘Oh yes. Absolutely. I’m absolutely fine.’

Kenneth gathers my things and hangs on to them. I pull myself up and hobble on. My ankle hurts quite a lot, actually. I imagine it swelling overnight, puffing up taut and pale.

‘You’re tired and emotional,’ Kenneth says, offering his hand as we walk past the whisky boutique.

‘I know I’m tired and emotional,’ I snap. Something too big is taking up the space in my chest.

*

The queue is full of people with the

We Get There First

bags. Instantly I am annoyed. Who are these people who get there first? And

why

do they want to get there? What are they trying to prove with these canvas bags? With these suits? These

enormous

suitcases on wheels?

I think of asking Kenneth but he is looking absent now, crunching a fruit sherbet, and I don’t bother him. I am, actually, very pleased to have Kenneth about. I don’t know how I would have got through this without him. We are three people away from the front now and he is watching all the despondent-

looking

suitcases as they are labelled with orange tags, placed on to the rungs of the conveyor belt and parted from their owners.

‘That one looks as if it belongs in an Inspector Clouseau film,’ he says, indicating an overstuffed red-and-blue tartan hold-all. I don’t reply. I’m thinking that even the brand new suitcases look over-hopeful.

When we get to the desk we ask for a window seat and a

middle

seat and watch our own blue and orange suitcases disappear miraculously through the theatrical little curtain. There they go. I can’t help wondering if we are to be reunited at the other end.

Now we have to look for Gate 34. Kenneth picks up his

briefcase

and my shoulder-bag and reaches for my hand. ‘Good,’ he says.

‘Yeah.’

He doesn’t say ‘Cheer up.’ He doesn’t find me a handkerchief. He knows when not to offer a handkerchief. And I love him for that. You don’t love that in a man when you are young. But later you do.

It was something about the suitcases,

I want to say. But I

suppose,

having grown-up daughters, he knows.

‘OK?’

‘Yes.’

‘Shall we go then?’

‘Yes.’

I allow myself to be lulled by the synthetic comforts of

Edinburgh

Airport: overheated WCs, fluffy toys, magazines, sock and scarf displays, all helping to alleviate the trauma of parting. A

kind of anaesthetic of blandness: the mild scent of coffee, the pink liquid soap, the over-large choc-chip muffins.

We have half an hour to wait for the plane. We skulk around for a while, in the environs of Gate 34. In the magazine shop we buy a copy of the

Guardian

and a copy of

Le Monde,

then go across to Costa Coffee and order two cappuccinos.

‘To go?’ the girl enquires.

‘Well, I suppose so,’ Kenneth says, looking at his watch. An aeroplane’s engines roar above our heads, and I wonder whether Jeremy Bowes is in it. ‘Seeing as we’re not staying,’ says Kenneth to the girl.

The girl takes a marker pen and writes something on to a large polystyrene beaker. Kenneth clears his throat.

‘We

are

going to sit down though,’ he says. ‘Briefly.’

‘Not to go, then.’ The girl sighs tetchily. ‘To sit in.’ And she crosses out what she wrote on the polystyrene beaker.

We don’t really sit in, there being no ‘in’. We sit up, our legs dangling from the high, uncomfortable silver stools.

A few feet away from me a young mother is attempting to feed her baby. She is sitting on one of the preposterously elevated stools, struggling to get him into the right position. And I

remember

that too: how difficult it was, fumbling with the bra strap, with the swollen, over-large nipple and the too-small

baby-mouth.

How were you supposed to hold your baby and keep him there? There had been nobody to show me what to do. This was in the privacy of my own bedroom, my discarded Cindy dolls staring crossly down at me from the top of the wardrobe.

You can breastfeed your baby anywhere: nobody need know!

commented the helpful baby books. The 1980s were so enlightened! But I never fed my baby in public.

*

The cappuccino is strong and rather bitter. I dunk my courtesy ginger biscuit into it and add a spoonful of sugar. Kenneth opens

the

Guardian

and begins to read. Lives falling apart, lives

reconnected.

Beside us a woman is addressing her husband. ‘I told her I’ve got pastry hands,’ she is saying, taking a sip of tea, the label

hanging

down the side of her cup, ‘because they’re cold, see?’

She pauses, and then reaches forwards and puts one of her hands on top of his.

‘I know you’ve got cold hands, Sheila,’ her husband sighs.

His wife gazes out through the big window.

‘I told her I’ve always had pastry hands,’ she says, ‘and Rita’s got bread hands.’

Kenneth sits and smiles at me, imagining, I suppose, a woman with ten bread rolls for fingers.

I stir my coffee.

‘Warm hands, cold heart,’ the woman says.

*

When our flight number appears I spring to my feet. Kenneth continues to sit, not seeing the need to hurry. There

is

no need, but I still do. Most people do.

‘The plane’s not going to go without us,’ says Kenneth.

‘Yes, I know that,’ I reply, picking up all my possessions. I seem to have accrued a lot more, even in the departure lounge. A

bagful

of newspapers and books. A packet of Simmers biscuits. Then there is my coat, my cardigan, my handbag.

Getting up a few seats away is a woman about my age who appears to have even more stuff than me. Impossible amounts of stuff. Propped against the side of her chair is a large black

portfolio,

and she stoops to pick it up. She is also carrying a plastic bag, a handbag with an inordinate number of buckles and straps, and a small rucksack. Swung across her left arm is her coat, a bright green thing – green as a privet hedge. And tucked beneath her right arm is a large, slightly battered-looking bunch of flowers. Gerbera, chrysanthemums, marguerites, more greenery. I

wonder

if the flowers were given to her by a lover or a husband. I

wonder

if her portfolio denotes that she was an embroiderer at the conference. A needlewoman of some kind, anyway. Or a designer, perhaps. Or a painter. And I feel obscurely jealous of her – of her artistic career, her brightness, her style. Maybe she has made more sensible choices in her life.

Now there is an altercation at Gate 34. A man with a

We Get There First

bag has lost his boarding pass. He raises his voice. An airport employee responds with a raised voice. I can’t hear the actual words.

Out of the corner of my eye I continue to spy on the woman with the portfolio. She is standing there in a slight dream, edging slowly forwards in the queue to Gate 34. With her flowers and her green coat and her silver-stranded hair she looks like a

middle

-aged water nymph.

As passengers begin to disappear through the departure gate, Kenneth finally gets up from the uncomfortable, metal-legged banquette. He walks over to me, smiles and looks at his watch. ‘How’s the ankle?’

‘Swelling up nicely. It’ll probably swell up even more on the plane.’

‘Well,’ he says. ‘We’ll be back in time for supper. Supper and a nice warm bath.’

‘Hmm.’

Why,

I am thinking,

am I drawn to this over-burdened woman?

‘Home in time to phone Joe.’

‘Mm-hmm.’

I am still watching her as she nears the gate. She says ‘Oops, sorry’ to an elderly man she has just whacked in the ribs with her portfolio. Then she makes a little movement: she tucks her flowers higher beneath her arm and twists slightly to reach into her pocket for her boarding pass – and it is the way she moves, leaning her portfolio against her leg, it is the way she knocks

something from her pocket on to the floor – a small, rattling, transparent box – that makes my heart jump.

I know who she is.

I know who she is.

And I don’t know what to say.

I put my hand on Kenneth’s arm. ‘Shush,’ I say.

‘What?’ he replies, ‘I didn’t say anything.’

‘Shush.’

‘What do you mean? What’s the matter?’

I look at her again – at the woman with the flowers who is

scattering

sequins all over the floor now, the lid having flown off the box, causing a tinselly, iridescent clatter of gold and silver and ruby and turquoise against the airport’s floor tiles.

‘Oh God, sorry,’ I hear her say to the fixed-face gate attendant.

‘Can you stand to one side please?’ the attendant says. ‘To let others past.’

‘Yes, sorry, I …’

‘I’m surprised those things didn’t show up in the X-ray machines.’

‘Yes, but they’re not metal,’ the woman says, looking up from her hunt. ‘They look metal but they’re actually …’

And she is hardly any different from the way she was when I knew her. She really isn’t. Even the way she pronounces ‘metal’ and the expression she has on her face. Serious. A little cross. It was never intentional, but there it still is. And the same flopping hair. And that billow of determination around her: something close to a cloud or a shadow.

I don’t know where to look. So I stare through the window. A man walks along the edge of a runway holding two round red boards which look like table-tennis racquets. A white plane

rumbles

past before heaving itself miraculously up into the air. And all the people at Departure Gate 34 look up at the aeroplane, and tut.

I turn my gaze back to the woman with the flowers and the scattered sequins. She has scooped up about half of them now and is looking around, a little pink-faced, at the irritated crowds.

I push my coat and bag into Kenneth’s arms and walk

forwards

a few paces.

‘This kind of thing always happens in the

worst possible place,’

Sally whispers to me.

‘I know,’ I say, as I kneel to help her.