Third Reich Victorious (32 page)

Once the U.S. and British attacks got under way, it was only a matter of time before the Axis forces were overwhelmed. The basic problem was supply. Von Arnim had told his superiors at Comando Supremo in Rome and in Berlin that he would need 140,000 tons of supplies per month to hold on to Tunisia. But in March less than 30,000 tons was delivered. In the face of Allied air and naval superiority, the Italian Navy and Axis air forces simply could not keep the troops supplied with the food, fuel, and ammunition they needed to defend the bridgehead.

4

In mid-May the inevitable happened—Axis forces in Tunisia surrendered, sending more shockwaves through the Axis alliance, especially Italy. Mussolini’s former supporters became more active in seeking to oust him. Multiple conspiracies began to take form. In Berlin, Hitler had to divert his attention from Zitadelle back to Italy. He immediately offered five new divisions to Mussolini for Italian defense. The Italian leader turned down the whole request, stating three divisions and 300 tanks would suffice. The response made Hitler suspicious of a possible Italian double cross. He ordered that Rommel’s command in northern Italy be expanded to thirteen divisions and established Operation Alaric—a plan to hold the western Alpine passes open and disarm the Italians.

Hitler’s troop movements into the area were still ongoing. There was little at present to stand in the way of an immediate Allied assault on Europe proper. This was especially true if the Italians collapsed. Most of his generals expected the Allies to follow up their African victory with an attack on Sicily and a concurrent invasion of the Italian mainland at Calabria to isolate the island. There was a single German division on the island, Division “Sicily,” and it was rebuilding. In addition, the Hermann Göring Panzer Division was regrouping in Italy itself. A tour of Sicily by Commander-in-Chief, South, Gen. Albert Kesselring, left serious doubts as to the Italians’ ability to defend their own soil. They had four mobile and six coastal divisions on Sicily, but Kesselring described the defensive preparations as “

reisenauri

” (one hell of a mess), with the fieldworks “so much gingerbread” and the coastal divisions “hopeless.”

This came at a time when preparations for Zitadelle were being assessed and changed. Hitler had already postponed the attack once to allow new weapons systems to reach the attacking forces. Panther and Tiger tanks, and Elefant self-propelled antitank guns, gave the Germans superior technology to the Soviets, but production was slow. The delay was making his generals nervous. In early May, Gen. Walter Model, whose 9th Army was to spearhead the attack from the north, shared aerial photographs showing extensive defensive preparations in his zone of attack. Field Marshal von Manstein, in charge of the southern assault, was seeing the same thing. He felt he could succeed if the attack took place then, but that the battle would be a toss-up in June. The conference ended with Hitler expressing concern but providing no decision other than to continue preparations and expect more delays.

As the Germans reconsidered, the Soviets and Allies continued their plans. In the East, the Soviet buildup around Kursk was occurring on a massive scale. Over 1.3 million, men and 3,500 tanks had been assembled in the Central and Voronezh Fronts to contest the coming assault. But the numbers were not the whole story. Each front had developed up to six defensive lines, filled with battalion defensive positions and antitank strongpoints. On the Voronezh Front alone the Soviets had dug nearly 2,600 miles of trenches, 300 miles of antitank obstacles, and laid over 600,000 mines. As an example, the 6th Guards Army, expecting an attack by von Manstein’s armor, had placed 69,000 mines and 327 pillboxes in its main line of defense, with 20,000 mines and 200 pillboxes in its second. Backing these armies were the front reserves, which included the 1st and 2nd Tank Armies, with the Steppe Front as the ultimate reserve. Also in support were three full air armies with 2,600 aircraft.

On the German side, the Zitadelle buildup continued. General Model’s 9th Army, scheduled to lead the northern assault, had built up to a force of some 330,000 troops, 600 tanks, and 425 assault guns. In the south, von Manstein’s main attack force, General Hermann Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army, had assembled 225,000 men and over 1,000 tanks and assault guns. Despite the massive buildup, however, there was rampant pessimism among the commanders about their chances, due to myriad delays and the evident Soviet preparations.

In the West, preparations for Sicily, called “Operation Husky,” continued as well. Ultra intercepts had indicated the Axis were expecting an attack on Sicily, so efforts were being made to confuse the issue with bombing and reconnaissance flights over Greece, Sardinia, and Corsica. The British suggested a more novel approach; in an operation they called “Mincemeat,” they planned to float a body ashore in Spain with letters from Alexander indicating Greece was the next target. Eisenhower turned down the suggestion as impractical.

Then, in early June, a major storm erupted between Germany’s opponents. Stalin had been demanding the Allies open a significant Second Front to take some of the pressure off his nation. Informed officially of Allied plans to invade Sicily and postpone a cross-Channel attack until 1944, he exploded. He told Churchill and Roosevelt that their delay was creating grave difficulties for his people, making them feel alone in the battle against the fascists. He pointed to the horrendous casualties suffered by the Red Army and called Allied losses “insignificant.” Operation Husky, in his opinion, was wholly inadequate. He needed an attack that would divert a significant number of the 200-plus German divisions facing him. The comment struck a sore point with Churchill, who had been stunned when the Husky planners informed him they could not guarantee success if more than two German divisions were encountered. Despite reassurances from both Roosevelt and Churchill, Stalin remained implacable, accusing the West of deliberately allowing his nation to destroy itself while defeating fascism.

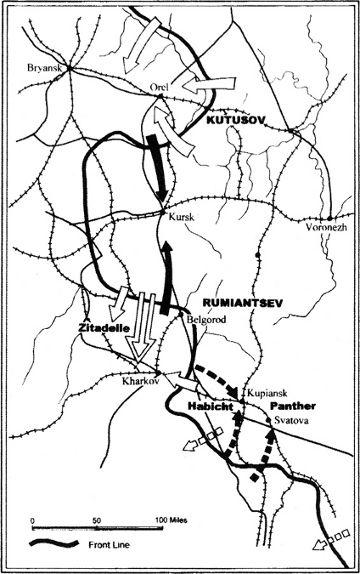

Map 10. Plans for Kursk

In June the Western Allies took steps to neutralize a threat to their Husky plans. The targets were the small islands of Pantelleria and Lampedusa which stood between Malta and the Tunisian shoreline. Both had Axis airfields and listening posts that threatened the security of the Husky transport fleets. Pantelleria was considered the primary threat and a difficult obstacle because fifteen battalions of coastal guns in pillboxes and 12,000 entrenched troops defended it. On June 7-11 over 5,400 tons of bombs were dropped on the island, blasting emplacements but causing only about 130 casualties. However, as the British brigade assigned to assault the island approached, the garrison surrendered, ostensibly because of the lack of water. Lampedusa surrendered the next day.

The fall of the two fortresses showed the Axis that Sicily would be the next target—and indicated to the Germans how well the Italians would defend their own soil. Once again Hitler had to switch his attention to the Mediterranean from the East.

On the island of Sicily, the only German division had been redesignated the 15th Panzergrenadier Division, built around three rather than the normal two Panzergrenadier regiments. But it was also integrating another Panzer battalion into its organization, which in effect would make it a very strong Panzer division (shortly renamed the 15th Panzer Division). Its troops were virtually all veterans, as were their leaders. In Italy, the Hermann Göring Panzer Division was nearly finished regrouping after its Tunisian withdrawal, regaining its infantry strength to complement its strong Panzer regiment. It received orders to transfer to Sicily. Two other divisions were rebuilding in Italy—the 29th Panzergrenadiers and 26th Panzer. Farther north, Rommel had collected the 1st Panzer Division, but only one of the promised eight other divisions, to hold in readiness for Operation Alaric.

Apart from the military aspects, the political climate in Italy would have been humorous had the impact not been so significant. German intelligence began picking up bits and pieces of a wide variety of conspiracies against Mussolini, all highly vocal but totally disorganized. However, the German ambassador to Italy, Hans von Mackensen, reported one coup was serious, but also told Berlin that one of Italy’s more extreme fascists, Roberto Farinacci, had offered to lead a countercoup against plotters in Mussolini’s own Fascist Grand Council.

5

The Germans began to take the political problem seriously.

On June 18, a week after the island of Pantelleria fell, Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), the German Armed Forces High Command, recommended to their Führer that Zitadelle be cancelled in order to keep strategic reserves free to respond to any threat. Again Hitler chose not to make a decision, still torn between needing the reserves and needing a victory over the Soviets.

But less than a week after OKW made its recommendation, the choice was taken away from the German leader. Two separate spy sources reported to Stalin that Zitadelle was no longer planned. “Werther” reported that “OKW does not wish to provoke a large scale Russian offensive in the central sector under any circumstances.”

6

The Soviets had put their fronts on alert for the German assault three times in May and once in June, just prior to the spy reports. Some of the commissars were pushing for Stalin to attack first. But the Soviet leader had demurred thus far. He knew the risk of attacking where his strength was concentrated—he would be driving right into the fresh, unbloodied troops the German had amassed—but he also knew that if he were going to attack anywhere, it would have to be where he had planned. To move his attack troops elsewhere would take reserves from the potential German attack zone and make him vulnerable if the Germans again changed their minds. With the spy reports now in hand, Stalin decided to wait no longer—against Zhukov’s advice, he ordered the Red Army to attack.

On June 24, 1943, the Soviets opened their offensive with two diversionary attacks. From the Southern Front, reinforced reconnaissance battalions crossed the Mius River and clashed with German outposts. That night, following a heavy barrage, the 5th Shock and 28th Armies attacked along a twelve-mile sector of the German 6th Army’s defensive line toward Stalino. The same day, the Southwestern Front sent its reconnaissance battalions across the northern Donets River, followed by the 1st and 8th Guards Armies, with the 23rd Tank Corps for exploitation.

Both attacks made slow progress against strong German defenses, developing small bridgeheads across the rivers but failing to penetrate much past the first defensive lines. But the attacks succeeded in their main purpose. Von Manstein dispatched most of his III Panzer Corps, the 6th and 19th Panzer Divisions, plus the 168th Infantry Division, south to deal with the threats to their southern flank.

Then it was the Soviets’ turn to be surprised. Their plans had called for a ten-day delay between the diversionary attacks and the start of Operation Rumiantsev, their main attack toward Kharkov, to allow the Nazi reserves to commit to those areas. However, as they waited, intelligence came in that made them alter their plans even further. Partisans around Bryansk reported that the Germans were building a new defensive line near the city and were pulling stockpiled supplies out of their forward supply dumps near Orel. It appeared that they were preparing to withdraw from the Orel salient that was the target of Operation Kutusov, the follow-on attack to Rumiantsev. In fact, Army Group Center had no orders from Hitler for any such withdrawal; its commander, Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge, had ordered the preparations of what he called the “Hagen Line” started as he and 9th Army’s General Model organized their arguments in favor of a withdrawal. Such a withdrawal would shorten the German line significantly, making more reserves available. To Stalin, however, such a withdrawal meant that the 2nd Panzer Army and 9th Army would escape his trap. This was unacceptable to him, and he ordered Kutusov implemented immediately.

The original plan for Kutusov called for concentric attacks from the north, east, and south into the Orel salient. On the north face, the Western Front’s 11th Guards Army, along with two tank corps, massed over 700 tanks and almost 4,300 guns for their breakthrough. In addition the Soviets had planned to exploit this hole with their new 4th Tank Army, but the schedule change caught this unit still in transit. To the east the Bryansk Front’s 3rd, 63rd, and 61st Armies prepared a straight-ahead assault, with the 3rd Tank Army and its 730 tanks moving up to exploit. Finally, on the southern face, the Central Front had three more armies ready to attack, with the 2nd Tank Army ready to follow them. All told, the Soviets were to unleash 750,000 men in sixty-seven divisions and 2,300 tanks on the German forces in the Orel salient.