Thirteen Chairs (12 page)

Authors: Dave Shelton

James glanced down at the form. ‘Well, I don’t know about that,’ he said. ‘But I think I’ll manage. Thanks. I’ll, uh, see you in a day or two.’ He made for the door and Mary waved him a distracted goodbye as she returned her attention to her record cards.

‘See you later, navigator,’ she said.

James didn’t get home until early evening in the end. After a fruitless visit to the Job Centre, and then a large, unhealthy, hugely enjoyable lunch in a café, he made a spontaneous trip to the cinema and accidentally saw the beginning and end (he slept soundly through the middle) of a black-and-white German film.

While he had been out, the story he had written hadn’t even crossed his mind, but now he was home he found himself thinking about it again. The exercise book was on the kitchen table, open at the final page of writing. He thought he would read through it one more time.

But when he sat down, instead of turning back to the start of the book, he unthinkingly turned over to a blank page. Why had he done that? he wondered. And then he noticed that he had picked up the pen

too, which was odd as he had no intention of writing anything. He had barely a thought in his head, after all.

Or he hadn’t. Now, actually, there

was

something, or the beginning of something, at least …

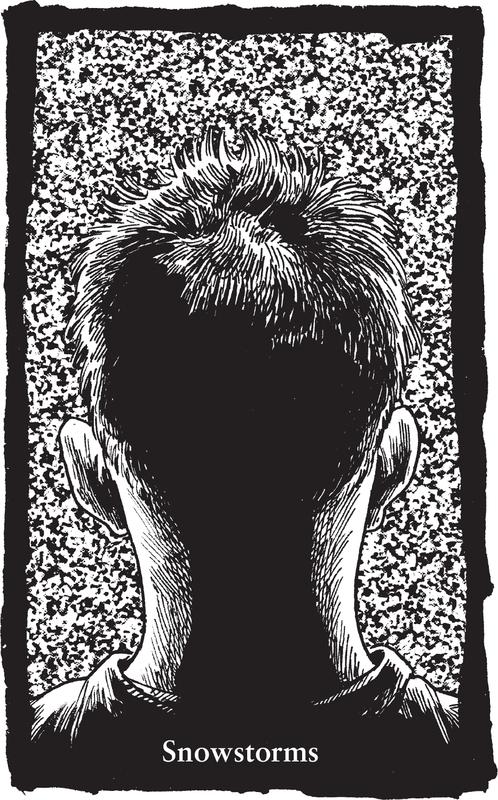

His hand hurt again, but it took some time to notice because his head hurt so much more. Something else was wrong too, if only he could work out what it was. Perhaps if it wasn’t so dark it would be easier. He wondered why his cheek felt so odd.

Ah yes, he was lying on the kitchen floor. That was it. One of his legs was tangled up in his chair, though he didn’t realize this until he tried (and failed) to stand up. Now his knee hurt too. He freed his leg from the toppled chair and carefully raised himself to his feet to take stock of the situation. He supposed he must have fallen asleep at the table and fallen off his chair. He touched a hand to his head and discovered that this was a very effective way of being in yet more pain. He stumbled about until he found the light switch, then made his way up to the bathroom to stand in front of the mirror and survey the damage.

He wasn’t bleeding. That was good. But his cheek was very red and he suspected that he’d gain a pretty respectable bump on his head by the morning. He parted his hair at the site of the pain and tried to take a look in the mirror, but he couldn’t really see. He was reminded again, though, of the stiffness and pain in

his fingers. He took a look at his right hand, turning it and flexing the fingers. The discomfort was freshly familiar, jolting his memory. He’d been writing again, he could vaguely recall. But what, he had no idea.

He had finished the first exercise book and continued into the second, almost filling that too. It was, he thought, an extraordinary amount of words to have written in one night, even if he had been just copying them out from a book. To have also composed them from scratch (and again written them out in a neat, compact hand without a single correction) in that time defied belief.

The pages rustled and flapped in his shaking hands as he flicked through them. He felt panicked and short of breath. What was happening to him? Where were they coming from, all these words? He put down the books, paced around the room for a while, his mind full of fast-moving nothingness. After some minutes he got his thoughts to settle, then he braced himself and sat down to read.

The thing that scared him most was not that this story was more brilliant than the last (though even he could see that it was), nor that it seemed only faintly familiar to him, even though he had apparently been the one to write it, nor even that the content of the story was so dark and twisted. What worried him was a single word on the penultimate page:

quotidian

.

He had no idea what it meant. He had never heard

it before, much less ever used it. Was it even a real word? He had no idea. But

he

had written it, apparently. Or at least his hand had held the pen that had written it. His steady hand. Not this one that was quivering before him now.

Mary wasn’t used to having customers waiting outside the library door for her to open up in the morning.

‘You’re keen,’ she said, but James rushed by her without a word, heading straight for the reference section. ‘Suit yourself,’ she muttered.

Quotidian

really was a word. What’s more, it was a word he had used perfectly correctly in a short work of fiction that, by any reasonable judgement, it was fair to say he was in no way capable of having written.

‘Have you filled in your form then?’ said the girl when he went unsteadily over to the desk.

‘No. Um …’ He fumbled in his pocket and found the form, looked at it with dazed puzzlement. ‘Er, yes. Yes, I have.’ He had indeed filled in the application form; it was just that he had no memory of doing so. He handed it over, then his driving licence and a letter from the electric company.

The girl nodded, filled in a form of her own and told him, a little brusquely, that he’d have his card in a few days.

James did not respond. He looked confused, a little lost. The girl was still trying to weigh up whether to ask him what was wrong, or tell him to leave, when

a short stout man in a tatty anorak, a flat cap and his sixties came in. He looked at James with wide eyes, overacting surprise.

‘Blimey, Mary. Two people in here at once? Haven’t seen that since the fifties. I hope they’ll be giving you some extra staff to cope.’

‘Morning, George,’ said the girl, smiling and handing him a copy of the

Financial Times

. ‘Enjoy your crossword.’ He shuffled off towards one of the tables. James hadn’t moved. ‘Was there anything else?’ she asked him.

‘Eh? Sorry. I, uh … I didn’t sleep too well last night. Look, um … this is going to sound crazy, but …’ He was looking to one side of her, avoiding meeting her eyes. One of his fingers was tapping erratically on top of a pair of exercise books he had put down on her desk. The last time she’d seen anyone so nervous in her company the man in question had proposed marriage (without success). ‘Er, look … do you …’ He shook his head, as if trying to rattle his thoughts into some sort of order. ‘Do you know how I could find out about who used to live in my house. In The Writer’s House? How could I find out who the writer was?’

‘Well, I suppose—’ Mary began.

‘French fella,’ said George, without looking up from his crossword. ‘I think French. Foreign, anyway. Before my time here, but I heard all about him. Young chap. Locked himself away in that place, scribbling away. Wrote two books then went mad.’

James’s face crumpled. ‘Mad?’

‘Well, he killed himself, anyway. Got to be a bit mad to do that, haven’t you? Funny lot those arty crafty types, aren’t they? Highly strung. Why d’you ask, though?’

But James was already halfway out of the door.

Mary thought more than twice about whether to go to the house. She had the address from James’s application form, but she figured that he’d probably be back once he realized that he’d left his exercise books behind. She also realized she could quite easily post the books back to him if that was her real concern.

But after a fortnight she still hadn’t. She’d read them in the meantime, though, several times over. She’d meant just to take a glance, kidding herself that she was checking in case James had written a phone number inside somewhere, but of course once she’d read the beginning she couldn’t stop herself.

She’d found out who The Writer’s House had belonged to as well. She’d asked a few of her regulars until a half-remembered title gave her enough of a lead to find his name. Then, out of interest, she’d tracked down copies of both his novels in other branches and had them transferred over.

When she read them she recognized the style at once.

The second book to arrive had been published after his death. It was a dark and disturbing story, but it was

the ‘about the author’ page that finally shocked her into action.

She drove to the house straight after work. There was no answer to her knock, but the door wasn’t locked when she tried it.

She was sure, as soon as she saw him, that James was dead. She stood in the doorway for a long moment, staring at the scene before her, shocked into a strange numbness. It was horrible but fascinating.

Perhaps because of the chaos around it, it was the neat pile of exercise books that held her attention. There was a reassuring normalness to them, order and familiarity (they were the same kind of books as Mary had used at school). They looked like something from real life. So she focused on the books, and chose not to dwell on any of the rest of it for now. In a daze she shuffled over to the table and picked up the books. They were numbered on their covers from three to six. As a librarian, and a respecter of the correct order of things, she dutifully opened up book three and, on an impulse, began to read.

By the time she had finished book six, it was the early hours of the morning. She slept briefly before she continued to read, slowly finding some order in the rest of James’s final writings: on loose sheets of paper, the backs of envelopes, paper towels and elsewhere. James’s handwriting had deteriorated as he went along

and this helped her to find the correct order, and told her at once that the writing on the table itself (still reasonably legible) preceded the less controlled writing on the walls, and that the wild scrawl on James’s own left arm came last.

She had expected an ending. She had, in fact, relied upon it. She had had to steel herself to read (with difficulty) the last words trailed over James’s pale dead skin, had known she should have stopped long ago, should not even have started. But the writing – the beautiful, elegant, seductive sentences – had compelled her to go on. Now they had run out she felt sick, twice over: once from gorging herself, and once for still feeling unsated.

There had to be an ending.

She searched the room frantically for some other, previously overlooked scrap of paper that might contain it, checked every surface, ran through the rest of the house in case it might have been set down in some other room.

At last she was forced to conclude that there simply was no ending. James had written himself to death, but whatever madness had forced him to do so, had kept him from sleeping or eating for days, had drained all these words and his life from him, had still not completed its task.

Back in the kitchen, dawn’s light breaking through the window, Mary sank exhausted to the floor. She glanced resentfully at James’s body sprawled across

the table top and then, appalled at this reaction, shook herself into recognizing the awfulness of what she had done. What had she been thinking? She would go now, return to town and telephone the police. Or should she call for an ambulance? She wasn’t sure. But she would go and belatedly do what was needed. She couldn’t believe how the writing had gripped her, nor how overwhelmingly she had felt the need for an ending to the story.

Well, there could never be one now, so there was no point thinking about it.

Unless …

A thought occurred to her. She had a notebook and a pen in her pocket. And there was a larger notepad in the car if she needed it. She was already onto the second page of the notebook, her writing dense and neat and flowing quickly.

James and the world fell away, and all that was left was words.

F

rances Crane sits still for a moment. She is leaning forward, propped up on one arm. Her head is bowed. She looks drained, as if the telling of her story has sapped all the energy from her, wiped away her playful smile.

‘Are you OK?’ says Jack.

Frances looks up at him. ‘Yes,’ she says hesitantly. ‘Yes, thank you.’ She throws him a cursory smile. A weak little thing that dies in a second. ‘That one affects me more than most for some reason, but I always forget. Maybe it’s because it reminds me of what happened to my writer friend.’

‘What was that?’

‘In the end he did run out of ideas. Suddenly couldn’t write anything more. And then, well, then I’m afraid he killed himself. And nobody saw it coming, because he always seemed so happy. That’s so often the way, though, isn’t it? Nobody sees.’ Then she manages another smile – a narrow, flat kind of a thing – before she blows out her candle and backs away into the thickening darkness.

‘Thank you,’ says Mr Osterley.

Three flames left now: Osterley’s, Mr Randolph’s and Jack’s, and the candles are burning low.

It doesn’t surprise Jack when Osterley calls upon Randolph to take the next turn. He had begun to suspect that this strange ritual must end with Jack and Mr Osterley facing each other alone in the light. But nor

is he relieved. Because Jack is beginning to realize what his story must be when his turn comes. And while he is scared to tell it, he will not run, because the other story – the story of this night of stories – is not yet over. And he wants to know how that story ends.

But first there will be Mr Randolph’s turn.

‘This is my own story,’ says Randolph.

He closes his eyes for a moment, and when he opens them again it seems to Jack that he has taken himself away somewhere, to another time and another place. And just for a moment there is a trace of a smile on that cold face of his.