Thirteen Chairs (11 page)

Authors: Dave Shelton

‘He’s wondering what to do next when fate takes a hand in the proceedings. The bear has run over to the bow rail and raised up his front paws onto it, as if he’s looking out at that departing wretch the cook, out in the jolly boat. At that moment a wave strikes the opposite bow and rocks the vessel suddenly over, far enough that the raging bear is sent off balance once again. Then as a loose barrel rolls fast across the sloping deck and hits him a heavy blow, the bear is tipped clean over the rail with a comical yelp.

‘The carpenter hears the splash as the beast hits the water, and then a deal more splashing and yelping and roaring as he surfaces. The next he sees of him, the bear is swimming, already at some distance. He dips and bobs with the waves, which are carrying him away from the ship, and the carpenter watches him awhile, as though he fears the beast may somehow climb back aboard to continue his mayhem. Then he carefully sets about descending to the deck. He is only three steps down toward his goal when there is a dreadful grinding, crunching noise and the ship throws herself sideways as if she wants to shake the carpenter off. For a moment he is hanging from the rigging by his one

good hand, his legs dangling over the waves. And, as if this weren’t peril enough for a blameless man to suffer, now he spies for the first time the tell-tale dark fins of prowling sharks.’

I confess I had a sudden urge to giggle at this point, and my attempts to mask my amusement with a cough were poorly acted. The sailor stopped his tale and those unnatural eyes fixed me from the dark.

‘Do you find my tale amusing, boy?’

He did not blink. I wondered then if he ever did as I could not recall his having done so the whole time he had been talking.

‘No, sir,’ I said. ‘I was merely startled by the misfortune of this fellow. To encounter a mad bear at sea is most unfortunate in itself. And now sharks. He is surely the most unlucky—’

‘Don’t,’ said the sailor in the quietest, firmest voice, ‘make light of his woes.’ His burning stare convinced me. I had been smiling, despite my wish to conceal my amusement. I was no longer. After a moment, he went on.

‘With no hand at the wheel to steer her, wind and wave have pushed the ship onto a reef, holing her beneath the water. So now here is further misery to amuse you, young sir. For the ship is sinking, and listing to one side as she goes down. The mast to which this poor devil the carpenter is clinging is leaning over ever more severely. He sees the waters lap onto the deck, gradually sweeping them clean of his dead and dying

shipmates, sees those bodies – alive and dead – pulled below amidst the thrashing fins and tails of the sharks. He clings onto the rigging in terror as the waters turn crimson and the mast bows down in supplication to those circling demons of the sea.

‘He grips his knife and readies himself as he dips into the churning waters. He’ll not go out gently, but it is a contest soon ended. The jolly boat is a speck in the distance by now, but the carpenter’s eyes are fixed firmly upon it and even as he is dragged below his mind and heart are full of dark fury at the cook’s foul treachery. Then there is darkness. The sharks eat their fill and within minutes all that remains of the entire crew are scraps of men at the bottom of the sea.’

‘But, sir,’ said I, ‘you cannot expect me to think this tale true, for, by your own account, every soul left aboard that ship perished. Only the treacherous cook escaped, and he too early to witness much of what you have related. And besides, you said this was a tale of revenge and yet no one remains to take that revenge.’

At this, I caught sight again of a dim scar of a smile within the shadows of the sailor’s face.

‘You’ve a keen mind, right enough, lad,’ he said. ‘You’ve reasoned that just beautiful. But there’s things as happen at sea that defy reason.’ He paused for a moment, as if distracted. His eyes flickered just a fraction up and to one side, as if he were looking at something behind me, and his smile widened. I turned to see

what possible sight might have amused so dark a soul and saw, on the contrary, only a sight to dismay me: my uncle emerging from behind the bar and striding angrily toward me.

‘There’s things as defy all explanation,’ said the sailor. ‘There’s rage that can outlive the mere shell of the body that it inhabits.’ He began to rise from his seat, and as he did so he raised a hand to that battered leather hat and pulled it forward from his head so that for a moment it obscured his face entirely, but I saw then that across his wrist was a most dreadful scar.

‘And if there has not yet been revenge,’ he said, as his hand dropped to his side and the hat to the floor, ‘then this tale is not yet ended.’

He stepped out from the shadows then and shrugged off that strange patchwork coat, and though the light was still dim, the full horror of his appearance was yet clear enough. He was a big man, but crooked and misshapen, his hulking frame somehow pulled askew. But there was no mistaking the power of him, nor his menace. The shirt he wore was ragged, one sleeve in tatters, the other missing entirely, and so revealed that the scar across his wrist was but one of very many.

These scars crossed and recrossed his arms, dividing up his skin such that it resembled a farmer’s fields divided by hedges, each area varying in colour and texture, some of them marked by the tattooist’s needle. And running along each scar was the same neat stitching as I had noted on his coat. Another such scar arced

down over his forehead then ran down beneath his eye and out across the cheek, the skin on either side of the stitching being of different shades. The greater part of that horrible visage was tanned and weather-beaten, but the smaller part confined by the scar was fairer and smoother, the face of a boy. The unholy, mismatched eyes glared with hateful intent and the mouth, all graveyard teeth and torn lips.

I heard my uncle emit an odd small sound behind me, part gasp and part whimper.

‘You?’ he whispered.

‘Aye,’ said the sailor. His right hand drew a knife from his belt as he lurched forward a step. I pushed back my chair and turned my head again. My uncle was backing away, in a slow, horrific trance, unable to find the will to run, transfixed by fear.

‘Did you think you could hide?’ said the sailor. He was beside me now and placed his free hand upon my shoulder, a gentle weight to persuade me to stay seated. ‘Did you think we would not find you?’

‘We? Oh, God in heaven!’ His eyes darted over the sailor’s body.

‘Aye,’ said the sailor. ‘The bear and the sharks between them made ugly work of us. But there were scraps enough left by the end still to build from. We have searched for you for so long, driven by burning rage. And now your captain’s eye has found you out. And you will die by your brother’s hand.’

Then the sailor stepped away from me, towards my

uncle, and as he did so his left hand, just for an instant, brushed through my hair with a gentle affection that I recognized at once.

Then it took the knife from the right hand, and set to its bloody task.

M

r Fowler’s story having come to an end, Jack feels disorientated and adrift. The blood-filled narrative had gripped him completely, and for as long as Mr Fowler had been relating it there had been no one and nothing else in the room. There had only been Mr Fowler’s face, floating in the darkness, the rich music of his voice and the terrible images drawn by his words. Now that it has ended, Jack feels abandoned. His stomach jolts inside him as if he is suddenly falling. It is a terrifying sensation that he tries hard to conceal. He gasps in a desperate breath and holds it, and the panic and the fear subside a little, his racing heart slows. He keeps his unblinking eyes set on Mr Fowler’s, and he smiles.

Fowler smiles back. ‘I hope that passed muster,’ says Mr Fowler.

‘Oh, it did, Mr Fowler,’ says Frances, her voice full of admiration, and even silent Mr Randolph gives a subtle nod of approval.

Jack nods too, though it was more than just the story itself that scared him; it was Fowler himself. Jack looks at him now. Rivers of shadow run along the cavernous lines of his face, widening and narrowing as the candlelight flickers, drawing and redrawing his features, as if he is one man with a myriad faces. All of those faces smiling, though. And it is a kindly smile, almost enough to reassure.

‘Thank you, Mr Fowler. If you please …’ says Mr Osterley.

With his eyes still on Jack, Mr Fowler leans forward. As he does so, the light hits his face at such an angle that, just for a second, his kindly smile is transformed into a sinister leer. Then he blows out the flame, pushes back his chair and all but disappears into the darkness.

It was only a trick of the light, Jack knows, but that snapshot moment was another crumb to feed that worm of doubt in his head, to make him reconsider what is possible, and what impossible, in the world. And he thinks again about the marks on Frances Crane’s wrists, and the worm writhes and turns and grows.

Just four flames left now, and the table is like a boat of light in a sea of darkness. The room has almost ceased to exist, and those who have already told their stories are just dim shapes in the gloom.

‘Miss Crane,’ says Mr Osterley. ‘If you’d be so kind.’

Frances smiles at him, all traces of her recent distress now utterly vanished. ‘Of course,’ she says, then addresses everyone else, in light or in darkness. ‘I think you’ll like my story tonight. Most of you, anyway. Some of you already know I was a painter, before. I used to have a lot of friends who were artists of one kind or another: painters and sculptors and dancers and singers and musicians and writers and poets.

‘This story is one that one of the writers once told me: not one he wrote, just one he’d heard somewhere. He was a good writer, for a while at least, but he was always worried that he might run out of ideas. Said he

hated that question that writers always get asked: “Where do you get your ideas from?” Because he didn’t know the answer, and that scared him. Anyway, because of that, I think, he was always very taken by this story. He told it to me a few times, actually. I think he told it a lot, and forgot who had already heard it, and I could never bring myself to tell him. But at least that means I can remember it well.’

J

ames was lost. He’d suspected as much for some time, but now he was sure. The man at the garage just outside town had given him directions, but James hadn’t written them down and now he’d forgotten most of them. He pulled the car into the car park by the library, just so he could stop and have a think. What he thought was that a library was probably a pretty good place to get some help. He got out of the car, stretched, and went in.

The library was a decent size, especially for so small a town, and well stocked with books, albeit mostly rather old ones. The carpet looked a few years past its best too. There was no one at the desk at the moment – in fact, there seemed to be no one else there at all – so he wandered around the shelves for a while, occasionally picking up a book at random and pretending to look at it while keeping half an eye out for a member of staff, but there was still nobody in sight.

‘Are you looking for anything in particular?’

James squeaked slightly as he jumped in surprise, then spun round to see a small young woman with an unusually tall hairdo, looking up at him with a smile. She had a badge pinned to her jumper that said

Senior Library Assistant

in printed letters and then

Mary

handwritten with a black marker pen beneath. Where had she come from? And were all librarians so quiet? Did they get some kind of special ninja librarian training?

‘Sorry. What?’ said James.

‘I said: are you looking for anything in particular?’

‘Actually, yes,’ said James. ‘I’m looking for my home.’

The girl thought about this for a moment, still smiling. ‘Well,’ she said, pointing to the nearest shelf, ‘I’m pretty sure you won’t find it in Zoology. Not unless you’re a snail, anyway. But then, a snail wouldn’t ever lose his home, would he?’

She had a good smile, warm and mischievous at once, but James was too tired to fully appreciate it, or her joking tone. In return he only looked bemused.

‘Sorry,’ said the girl. ‘You’re looking for your home. How do you mean? And how can I help?’

‘I’m moving into my new place today. I rented a house near here – at least, I

hope

it’s near here – only I got a bit lost. I’ve been driving around for ages. I spent quite a while wondering why a town as small as this had two libraries. And then when I saw the third one, and it looked exactly the same as the other two, I finally realized I was going round in circles. So I thought I’d stop and ask for some help.’ He pulled a helpless face. ‘Help?’

‘Yup,’ said Mary the assistant librarian. ‘That one-way system doesn’t let go easily, does it? You know,

my theory is that half the population of the town never actually meant to live here; they just came to do some shopping and never got out. Shall I draw you a map?’

‘That’d be great. I got some directions from the bloke at the garage up the road there, but I forgot most of them. He called it The Writer’s House. You don’t know anything about that, do you?’

‘Afraid not, no.’

So James told her the address of the house and Mary found a road atlas and drew him a map. While she did, James browsed through the old books on a trolley by the desk, marked

Book Sale. Withdrawn from stock.

James picked one out almost at random, a thick, battered paperback priced in pencil on the first page at 25p. It wasn’t the kind of thing he’d usually buy, but he took it anyway, paying with a handful of change as Mary handed him the map.

It wasn’t far, and when he got there it didn’t take long to unpack. James had brought everything he owned in the world with him, and found that it had fitted all too easily into the boot and back seat of his car. And it wasn’t a big car.

His life had gone a bit wrong lately, but this was to be his fresh start. He arranged his few possessions in their appropriate rooms while listening to music he didn’t like on his radio. The house felt empty and unfamiliar, but then, he reasoned, it

was

empty and unfamiliar.

When he was done, he made a mug of tea and sat on his bed to read for a while. He wasn’t usually much of a reader (it was odd that he’d bought the book at all), but for the time being he had no television, so he ploughed through the first few chapters. It was diverting enough, just a cheap thriller: dumb and action-packed, like the films he usually watched. In any case, he liked it enough to keep reading. In fact, it was odd but, while he knew it wasn’t very good really, he found – for the first time in his life – that he just wanted to carry on and on reading it.

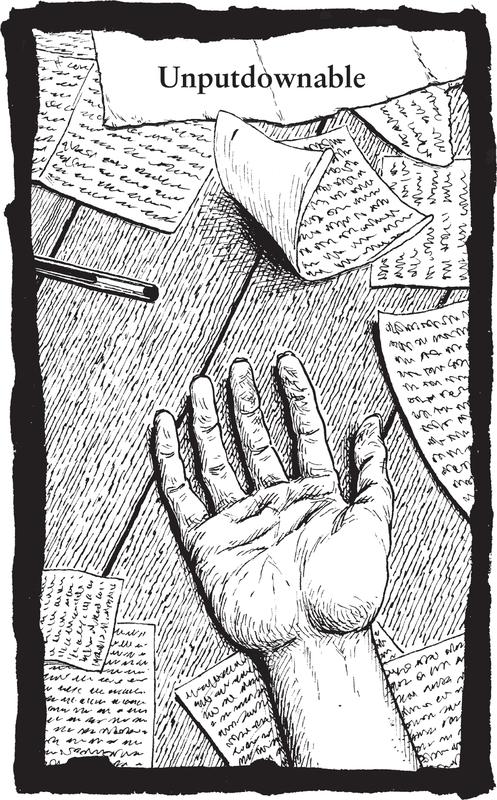

He had never understood before when someone called a book ‘unputdownable’, but here he was frantically turning the pages, drinking in every badly written word, devouring the pages like a starved man, reading much faster than he’d even known he was able to. He read on, longer than he’d intended, only rather briefly (and reluctantly) stopping to make and eat some supper. Then, with nothing pressing to occupy him after his meal, he decided he might as well continue. He raced through a few chapters in the armchair in the sitting room and then, when he started to feel chilly, he took the book to bed, intending to read just one more chapter before going to sleep.

He finished it at 3.35 in the morning. He was puzzled that he’d needed so badly to get to the end, but by then he was too exhausted to really think too much about it. He slept deeply and solidly, but only until a little after dawn. Almost immediately on waking

he started to think about the book again. He hadn’t liked the ending. His guess at who had committed the murder had been wrong, and he’d been disappointed by that. Only now he thought that it wasn’t him that was wrong: his was the right ending; the author of the book had got it wrong.

He got out of bed just long enough to find a pen, then he got back in and turned to the back of the book. There were half a dozen blank pages right at the back, and with his cheap biro he started to write on these, in tiny, densely packed letters. Just for fun he wrote down his own ending to the story.

James was surprised to find that it came to him easily; it felt as if he wasn’t even thinking about it. As if he wasn’t thinking of the words and

then

writing them down, but instead he was writing them down and then reading them. He was amazed and delighted by himself. He hadn’t ever thought of himself as having a good imagination, or that he could write particularly well, and yet here he was pouring words onto a page (onto several pages) with the same determination with which he had read the book the previous night. He finished at the very end of the last page – a perfect fit – and sat back in the bed, slightly breathless, elated and startled.

He flicked through the pages. There were no mistakes, no crossings out, no corrections. He read the occasional sentence here and there as he glanced through. It seemed to be good. Better, he thought, than the writing in the book itself.

‘Well, where did that come from?’ he said to himself, aloud. He stared at his hand accusingly. The pen had leaked some ink onto his fingertips and now the hand almost didn’t feel or look like it belonged to him. It was all very odd, but he guessed that he was just a bit disorientated by the move and a general feeling of not yet belonging. A huge yawn took hold of him and pushed such thoughts away.

‘Breakfast,’ he said, and got up and had some.

After breakfast, James drove to town. He went to a supermarket full of harsh light and chirpy music and bought a number of things he needed for the house. He had written a list earlier and then left it on the kitchen table when he came out, but he was pretty sure he had remembered everything. He also got a few things that hadn’t been on the list but that suddenly seemed necessary once he saw them on the shelves. Then he made an excellent job of finding his way home again, only passing the library twice this time.

Back home he swore at himself briefly once he found his shopping list and realized all the things he’d forgotten, then he set about finding places for all that he had bought: this cupboard for plates and dishes; this one for cups and glasses; this one for jars and tins; and so on. There was little enough that it didn’t take him long.

A couple of the items that he had bought on impulse he left out on the kitchen table: a packet of six exercise

books and a pack of a dozen cheap ballpoint pens. James sat at the table and stared at these. He couldn’t remember why he’d bought them, but thinking back he remembered he’d felt a small thrill as he placed them in his trolley. Stupid, really. Oh well, now that he had them, the exercise books might as well be of some use, he thought.

He tore open the plastic wrapping and took one out. He needed to be more organized from now on, he told himself, so he decided to write a proper shopping list for tomorrow, and a list of things he needed to do. He took a pen from the box and removed the cap.

But he didn’t write a list because, as he folded back the cover of the book and looked at the empty page of lined paper beneath, a thought occurred to him. He found he was thinking about a child he had seen sitting on a low wall outside the supermarket: a girl, maybe twelve years old. She looked as if she needed to cry but wasn’t going to let herself. She was holding her lips tight together, looking first off to one side and then the other, as if trying to shake off the attention of anyone who might look at her. James had wondered what her story was.

And then, because he couldn’t know, he made one up.

It was almost dark, and he was hungry and his hand hurt. He felt as if he had just woken up, but he wasn’t in bed: he was sitting at the kitchen table. He got up

and switched the light on, feeling woozy and unsettled, stretched his arms out and his head back, trying to work the tension out of his muscles. He wished he could do the same for the tension inside his head.

Then he looked down at the kitchen table and saw the exercise book. It was open at a page about two thirds of the way through, a page covered in writing. When he picked up the book and looked through it he found that all the pages before that were the same. It was his handwriting, but he had no memory of writing it. James dropped the book onto the table in shock, backing away from it as if afraid. Was he going mad? When he had calmed down a little, he made a cup of tea, glancing at the book suspiciously out of the corner of his eye as he did so. Then he sat, picked up the book gingerly, swallowed hard, and began to read.

It was really good.

At least, he was fairly certain it was good. It was much better than James could ever believe he was capable of writing, that was for sure. But there it was, in his handwriting, and as he read it there was a dim ring of familiarity to it, as if he’d at least

read

the story before. But how could he have written it? He didn’t write. He couldn’t even

tell

stories very well, much less write them. But here was the story of the crying girl, richly imagined and set out in precise detail, beautifully and touchingly written.

It was amazing. Frightening too.

He remembered a story he had heard on the news

once. There had been a man who had been hit on the head and had suddenly found that he could play the piano rather brilliantly, despite never having done so at all previously. He wondered if the same thing could happen with writing. And without being hit on the head. The whole thing seemed crazy. Luckily, his hunger helped distract him, and he set aside the book to make himself some cheese on toast.

He wolfed it down, in that way that you can when you’re on your own and nobody’s watching. Then he made more and did it again. At the end of it he felt full, sated, fulfilled. Elated, in fact. And not at all tired. He couldn’t decide what to do next, but

anything

seemed possible.

Ten minutes later he was fast asleep, fully clothed on his bed.

When he awoke, late the next morning, he felt amazing. There was an energy in him like he had never known before, and a feeling of deep satisfaction. He sang to himself as he made a huge bowl of porridge for his breakfast, far too much for only one person. Then, when he had eaten it all, he had two lots of thickly cut toast, generously buttered and laden with jam, all of it washed down with mugs of tea. And it all tasted incredible, like the best porridge, the best toast, the best jam and the best tea ever made. He felt incredibly alive, his skin singing, his mind happily racing.

He looked at the exercise book, half expecting it to

be empty, to discover he had dreamed the whole thing. Or else it would be full of gibberish. But no; it was as he remembered it, still (so far as he could judge) very good, maybe even brilliant. This morning he found it easier to just accept it, somehow. And he had other things on his mind too. He had decided to look for a job, just temporarily. He had enough money put aside that he could get by for a while, but he wanted something to do, to keep his mind and body occupied.

Another trip to town, to the Job Centre, was called for, so he showered and dressed and drove off in his complaining heap of a car.

He hadn’t planned to go to the library, but the car park beside it was convenient, and while he was there he thought he might as well. The same girl, Mary, was behind the desk, filing buff-coloured record cards. She looked up at the sound of the door opening.

‘Oh, hello again, Lost Boy. Did you find your way home, then?’

‘Um, yes, thanks.’

‘And now that you’re living in the neighbourhood, I suppose you figured you’d join the library, like all solid upstanding citizens should?’

‘Er, yes,’ said James. Actually, the thought hadn’t occurred to him even for a moment. He hadn’t ever joined a library in his life – why would he? But now, somehow, the idea appealed. ‘What do I need to—’

‘Here you go.’ Mary plucked a photocopied sheet of paper from a plastic holder on the front of the counter

and offered it to him with a theatrical flourish. ‘Just fill in this form, bring us some ID and proof of address, and that’s pretty much it. I’d take you through it in detail, but it’s all pretty self-explanatory, unless you’re some kind of idiot. And you want to join the library, so you’re clearly not.’