Thirteen Chairs (6 page)

Authors: Dave Shelton

He shook and he trembled and he rocked.

‘Please make it stop!’

As if in answer to this plea, all the noise ceased: the ticking and the dripping and the gasping sobs.

And the heartbeat too.

The notebook dropped from his hand, but Professor Seabright was not living to hear it hit the floor.

P

rofessor Cleary smiles broadly, leans back in her chair. It seems to Jack that she looks rather pleased with herself. And, looking at the others, it seems as if she has good reason to be.

The previous stories were greeted with appreciation, certainly, but this one seems to have had a deeper effect on its audience. Some look rather shaken by it – eyes fixed, tight-faced, tense – which, Jack assumes, is the desired response. Only Mr Osterley seems unmoved, retaining his same detached calm. Amelia, the young girl by Jack’s side, is fidgeting more than ever, though. She looks agitated.

‘Are you OK?’ says Jack.

She glares back at him. ‘Course. Yes. Fine.’ But she turns her head quickly away again, as Jack does likewise.

He doesn’t understand. It didn’t seem such a very scary story to him, at least no more so than the others. Has he missed something? Because everyone seems to be dumbstruck.

‘Well done, madam,’ says Mr Fowler at last. ‘We seem to be lost for words, so I suppose your words must have struck home.’

‘Good,’ says the professor. ‘I’m so glad you enjoyed it.’

‘Oh, he didn’t say he enjoyed it,’ says Katy Mulligan, the young woman with the severe-looking haircut. ‘I’m not sure any of us enjoyed it, Miriam.’ She fixes a hard look on Professor Cleary. ‘But I suppose it worked.’ She gives a small nod.

Professor Cleary grins smugly back at her. ‘Yes, it served its purpose rather well, I think,’ she says. ‘Got to the heart of the matter, as it were.’

Katy Mulligan scowls at her, and seems about to say more, but Mr Osterley quietly cuts in.

‘Quite,’ he says, and though his expression seems unchanged, and his tone of voice is soft and even, there is somehow a firm authority to that one word, and both the professor and Ms Mulligan fall silent. ‘Thank you, Professor.’ A small turn of the wrist and a lazy wave of the hand invite the professor to extinguish her candle.

The professor accepts, blows out the flame with an exaggerated pout, and slides her chair back without a word.

‘Very good,’ says Mr Osterley. ‘Perhaps it is time to hear from one of our younger guests now.’ Jack’s chest tightens, but Mr Osterley, with a typically slight gesture, is indicating the boy to Jack’s left: tall, stooping Lee, who nods and mumbles in reply.

‘Oh, uh … yeah. ’K.’ He raises a skinny arm to rest a hand on the back of his neck, as if it is not yet bowed low enough and he might be about to tug it down another few centimetres. His other hand ruffles through his hair for a moment. ‘Yeah, well, it’s, um … odd. It’s an odd story but … Well, you might not think it’s very … Anyway …’

And then he coughs.

And then he says ‘Um’ again.

And then he begins.

T

hey all fell into the water when the boat went over, but Jonah was the only one who woke up in the hospital that night. He heard the doctors talking about him when they thought he was asleep.

‘He ought to be dead too. That long under the water … It’s some kind of miracle.’

They didn’t show him his parents. And they couldn’t show him his brother; they never found him.

Now his aunt and uncle do their best, but they’re deadened by grief, and they never wanted children of their own, and it shows. Jonah’s room in their house used to be the spare bedroom, and that shows too. It’s as if he’s just another guest expected not to outstay his welcome. He tries his best not to get in the way. He helps out with chores. He does his homework quietly in his room. He reads a lot. Sometimes they all watch television together. Comedies, mostly. They like canned laughter on the soundtrack to remind them when they’re meant to laugh. It’s too easy to forget otherwise.

They don’t talk about Jonah’s mum and dad, or his brother. They sleepwalk from day to day. No one seems to notice. Life, or at least something superficially resembling it, goes on.

One day, Jonah is walking home from school along the towpath by the river; he goes this way fairly often and some of the people who live on the houseboats recognize him and give him a wave and a smile. He comes to a bend in the river where there are no boats, and he’s alone on the path when he thinks he sees something move in the water.

He goes over closer to the edge and gazes down. It looks like the mud at the bottom has been disturbed. It’s swirling about in billowing grey clouds that are just beginning to settle, and he sees that fish are swimming away from there, but he can’t see what’s kicked the mud into motion to begin with. He stares, puzzled for a minute, then turns to go, but slips on the bank, falls onto his front, and his feet slide down the grassy slope into the water.

His legs are submerged as far as his knees before he grabs hold of a mooring post and brings himself to a stop. So then he’s lying there feeling foolish and pulling himself back up out of the water, and the wet material of his trousers is clinging to his legs, when something brushes against his foot. A fish or some weed, he supposes, just glancing against him, but enough to make him jump.

He scrambles up the bank a little way and turns to look at the water, his arms clutching his wet knees beneath his chin. The clouds of mud he’s stirred up settle, the rippled surface of the water flattens and everything goes still. And now he’s wet, flustered and

embarrassed, as a couple of older girls from his school pass by giggling. He runs home and races upstairs to change his clothes before his aunt and uncle can see him.

Later they have dinner and make the usual polite chitchat. His uncle’s day at work was ‘fine’, his aunt’s was ‘fine’, Jonah’s day at school was ‘fine’. He doesn’t even consider telling them about what happened at the river. He’s almost forgotten all about it himself.

Then one day in the following week, it rains during the morning, and when Jonah sets off back home the roads and pavements are still wet. He cuts through the old precinct where Barker’s, the newsagent, used to be. When he was young, he and his brother would buy sweets there when they were visiting Auntie Jane. There are puddles scattered around the courtyard, and in one corner the paving slabs are cracked and tilted, forming a mini lake of rainwater.

Rather than detour around it Jonah decides to jump it. He takes a running leap, and as he passes over the puddle he catches sight of his reflection in the water. Only it isn’t him. It’s someone else’s face that he sees there, pale and blank, looking up at him with wide eyes. It’s his brother – his dead brother – staring up at him out of a grey puddle of water in a rundown shopping precinct.

Jonah lands badly, falls painfully to his hands and knees, feels his lungs empty. When he gets up he doesn’t

look back at the puddle. He walks away quickly, runs home.

Everyone has had a ‘fine’ day and his aunt and uncle don’t notice his grazed palms. After they’ve eaten and Jonah has done his homework they watch a film on the television and laugh in all the places where it seems like they ought to.

The next day, Jonah tells his aunt and uncle that he’s feeling ill and can’t go in to school. They don’t ask questions, except to check that he’ll be all right left alone all day while they’re at work. There’s a subtle implication that, if needed, one of them will take the day off to be with him. But there’s a much less subtle hint that they’d rather not.

Jonah says he’ll be fine on his own. Says he’ll just read in bed and get some rest, and so they go to work. Then Jonah plays computer games all day, with the sound on headphones, and ignores the noise of the rain against the windows.

A wet weekend passes in a similar fashion. Jonah’s aunt and uncle make suggestions for trips out, but he says he’s happy to stay in ‘just to be on the safe side’, even though he feels much better, and they’re happy to accept this and do their own thing without him.

Monday is sunny and dry and Jonah declares that he has made a full recovery. School is ‘fine’. He gets the bus home for a change, even though walking would probably be quicker. He sits on the top deck near the back, playing games on his phone and misses his stop.

When he gets off at the next one it’s starting to rain again, even though the forecast on the radio in the morning had said dry all day. It’s one of those sudden showers, the kind that goes from nothing to a downpour in a second. The pavement is instantly awash: one vast puddle churned into chaos by the torrent of rain. Jonah runs homeward, eyes ahead, ignoring his fractured reflection beneath him. The street is almost empty of other pedestrians, though it’s hard to see for sure through the dense curtain of rain.

He turns a corner and comes to a sudden halt. Directly ahead of him there’s a kind of shadow in the falling rain. Only it’s not a shadow – it’s more of an absence. The hard straight lines of rain are broken, as if hitting something invisible. It’s hard to make out exactly what, but it’s a little shorter than Jonah, and roughly the shape of a boy.

‘Joe?’ he says, and shivers. He hasn’t spoken his brother’s name since he died, and the taste of it on his lips now is bittersweet. He lifts a hand slowly up. Reaches forward towards the apparition, trembling and expectant.

The kid on the skateboard is a bit younger than Jonah, and going too fast to do anything about it when he rounds the corner and finds himself headed straight towards Jonah’s back. Jonah doesn’t hear him coming, only feels the impact. He’s thrown forward, arms splayed like frantic wings, and lands heavily on the wet paving slabs, adding fresh grazes to his palms. The

boy lands on top of him and winds him. He mumbles something that might either be an apology or swearing, and then he’s back on his skateboard and speeding away just as recklessly as before.

When Jonah gets up, there’s no gap in the rain any more, just a relentless torrent.

Stair rods

, as his dad used to say. Some of his books have spilled out of his school bag. He should gather them up before they’re ruined, but he’s too distracted. He’s thinking about stair rods and he doesn’t know what he’s feeling.

At home, everything has been ‘fine’ for everyone, except for the weather. Jonah doesn’t feel like trying to laugh at the telly so he goes up early to his room to do homework and read. With headphones on and the music turned up loud, concentrating hard on his book, he barely notices the sound of the rain on the window. He doesn’t hear the knock on his door at all. His uncle appears behind it as it swings open.

‘We’re just nipping out. Jenny called and we’re off round to hers for a while. Do you want to come?’

Jenny is a woman a couple of streets away. Jonah is scared of her gigantic dog and her strangely immobile hairstyle. He says he’s happy just to stop in and carry on reading. Uncle John seems perfectly happy with this too.

They’ve been gone about an hour when the lights go out. Jonah peeps out of the window and sees that the streetlights and the lights in the other houses are still on. He knows there’s some kind of fuse box in the basement – the lights had gone out once before a couple of

weeks earlier, and Auntie Jane had gone down to reset the switch.

Jonah uses his phone to light his way safely downstairs, gets a proper torch from a drawer in the kitchen, and then opens the door to the basement. He’s only been down there once before, when he first moved in. He’d brought along more stuff than could fit into his room, so some of it had gone down to the basement temporarily.

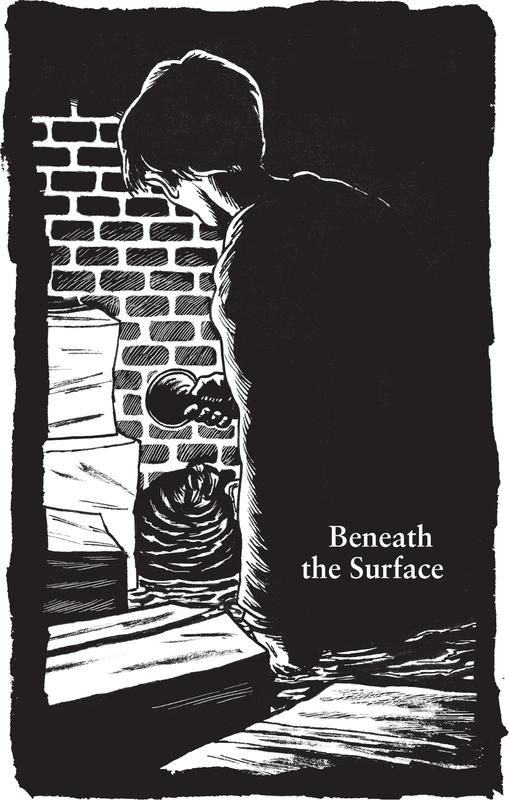

The stairs down are narrow and creaky and there’s no banister, just a (slightly wobbly) handrail running down the wall, so the other side is open, with the potential for a longish drop if you misstep near the top. It isn’t much of a worry when you can see where you’re going, but somehow in the darkness it seems much more of a danger. Jonah keeps the torch trained studiously on the steps beneath his feet and edges down slowly. When he gets to the bottom step, he notices something strange: the pool of light at the end of the torch’s beam has ripples in it.

Standing still, he tracks the torchlight over the floor of the basement. It is entirely covered in water. He flicks the torch beam up to the back wall. Right near the top there’s a small barred window, opening to the outside at ground level. It’s been broken for years (the result of a mishap with a cricket ball that Joe and Jonah had each claimed was the other’s fault), cracked and holed and letting in torrents of rainwater, directly onto the fuse box.

It takes Jonah a moment to realize what has happened: the river runs through the meadow behind the house; it must have burst its banks, flooding the garden and then leaking into the basement. He points the torch around the room, piecing together the full scene from the fragments freed from darkness by its beam. The floor is a shallow sea with islands of all the boxes and junk that are kept down there.

One of those boxes – one of Jonah’s boxes – is full of photographs. He decides that before he phones Auntie Jane’s mobile he’ll get the box – full of his past, full of his dead family frozen in life – out of harm’s way. A little more scanning around with the torch beam finds the particular box in a far corner.

Jonah steps down from the bottom step and moves toward the box. But when he steps out, the floor isn’t where it ought to be. Though the water can’t be more than a few centimetres deep, his foot drops ankle-deep beneath the surface, as if going down one more step on the staircase. Thrown off balance, Jonah lurches forward. His other foot goes forward to steady himself – and drops another step down.

But there isn’t another step there. Jonah can see boxes across the room that show with certainty the level of the floor. But his feet are beneath it. He is standing shin-deep in no more than two centimetres of water. It makes no sense at all. But he is puzzled rather than alarmed.

Jonah steadies himself as best he can, wobbling and

waving his arms. As he does so, the dancing torchlight flits over something else odd happening. In the centre of the floor the water is moving, bulging up in a way that water can’t do, forming itself into a tiny hill that continues to rise, grow, and shape itself. He steadies the beam of light to watch it, still strangely calm.

In a few seconds a bizarre effigy stands before him: water in the shape of a boy. The features are unclear – they ripple and change – but he knows it is his brother.

He knows it is Joe.

The watery figure raises a hand slowly, and Jonah raises his own hand to match it. He looks into his brother’s face – his face made of water, that he looks

through

as much as

at

. And he feels something, as he did when he saw the reflection in the puddle, and again when he saw the figure in the rain: it had been fear to begin with, but now it’s a sad longing, a slow, long ache of loss.

Then this ghost made of water turns and walks slowly away, and with each step he drops lower in the water, as if the staircase continues on, down below the basement floor.

Jonah follows him, sinking deeper into the water with each pace. As the apparition’s head dips beneath the surface Jonah laughs. A real laugh. Then, without really thinking about it, he holds his empty breath, and steps down and down.

Now the water is over his head. And now there is

nothing beneath his feet any more and he drops slowly down, deeper into the impossible water. He lets go of the torch and it sinks away from him, still shining, twirling away into distance and darkness. He feels his hands being held: one by soft, slender fingers; one by a larger, rougher hand.

And he laughs again, and water fills his lungs.

Somewhere beneath him the torch dies, blinking into nothingness, and Jonah sinks happily into the welcoming dark.