Thirteen Chairs (3 page)

Authors: Dave Shelton

M

r Harlow’s head is slightly bowed over his notepad, and he remains hunched and still for a moment. Then he taps a finger lightly, once, on the open page, as if placing a final full stop, and closes the pad. Only then does he half raise his eyes to look for a reaction. The others gently nod their approval.

‘Thank you,’ says the pale man, with a slow small bow of the head.

Jack closes his eyes and shakes his head, as he tries to dislodge from it the images that the story has put there: not only those that the story described, but also the ones that Jack has imagined for the moments after the end. He doesn’t want them in there.

‘Thank you, Mr Osterley,’ says Mr Harlow quietly. Then, after a pause, he draws in a modest breath and blows out his candle. He allows himself a weak smile as he pushes his chair back from the table, away from the light, and leans back, happy to retire into darkness.

‘Yes. Thank you, Mister Harlow,’ says Piotr the giant. His impressively bushy beard quivers with glee as he speaks in a heavy accent that Jack can’t quite place. ‘Is very good tale! Is magnificent. It give me the geesebump, is so scary! And I am bravest man from my village. I do not scare so easy! Oh no! Not on my nelly!’

‘Thank you, Piotr,’ says Mr Osterley calmly and quietly. ‘Your enthusiasm has been noted.’ There seems to be no reproach in his voice, but still the big man falls

instantly silent, like an over-excited schoolboy who’s been told off.

‘I just like story,’ he mumbles, hunched over now, as if trying to compress his immense frame into a smaller shape.

‘Oooh, and quite right too,’ says a woman’s voice. Jack looks over. She is quite small, this woman, and enormously untidy. Everything about her is untidy: her clothes, her hair, even her skin somehow seems to be the wrong size for her. She looks like a baby bird with scruffy explosions of tangled hair that set off in a variety of directions from her head, like patches of newly sprouting feathers. ‘It was a smashing story. Well done, Mr H,’ she says. Her head jerks as she speaks, her eyes swivelling madly to maintain a fix on whoever she’s looking at. She reminds Jack of his great-aunt Millie. She might easily be just as mad too, the association makes Jack feel a tiny bit more at home, just a little more at ease. She gives a strange little laugh. ‘Ooh, yes, just smashing.’

‘Perhaps,’ says Mr Osterley, ‘we might have your contribution next, Mrs Trent.’

‘Ooh, now, dear, you really must call me Josephine. I can’t be doing with formality, me. I’ve no time for it.’

Mr Osterley’s lips purse, just the tiniest amount, and he pauses before he speaks again. ‘Josephine, then. If you would be so kind.’

‘Of course, my dear. Of course. Now then, tonight

I thought I’d tell you a story that happened in my own village. Imagine! Ooh, it were quite a to-do at the time, I can tell you. Do you like cats?’ Grinning and twitching, her head angled up one way, her eyes turned to look in another direction completely, it’s impossible to tell if she’s asking anyone in particular, but in any case she doesn’t pause for a reply. ‘Some people go all soppy for them, don’t they? Never understood it myself. I quite like a dog, you know, if it’s the right kind of dog. Nothing too small and yappy. But cats I don’t really have time for, myself, and—’

‘If you would be so kind, Josephine, please …’ says the pale man. There is only a tiny grain of exasperation in his tone, but it works well enough. Josephine’s jolting head comes to a standstill and her eyes rest briefly on Mr Osterley’s still, expressionless face.

‘Of course,’ she says, and balls her bony hands up into tight fists. ‘Get on with it, Josephine. Well, then. Here we go.’

W

ell, it was a funny old business from the start. From before the start, even. But I’ll start at the beginning anyway. I can always go back, now, can’t I? Oh, but then, when

was

the beginning? Well, there’s a question and no mistake. But I tell you what I’ll do: I’ll start with Helena. I’ll start with Helena dying.

So Helena died. Well, you knew that already, I just said.

Oh, anyway, Helena died, but nobody was surprised, because she was very old and she’d been ill almost for ever, and nobody cared very much because, well, let’s be honest: she was a horrible,

horrible

woman.

Nobody

liked her. Even the other people in the village that nobody liked: they didn’t like her either.

And Helena, so far as anyone could tell, didn’t like anybody. She’d been a difficult and lonely child, and over the years she’d grown into a difficult and lonely old woman. A difficult, lonely, bitter, spiteful, poisonous old woman. She lived in a big old house away from the main village and she’d go days without seeing anyone at all, which suited her. And, to be fair, it suited everyone else too. Well, you can imagine.

So she was lonely, by choice, but she did have her

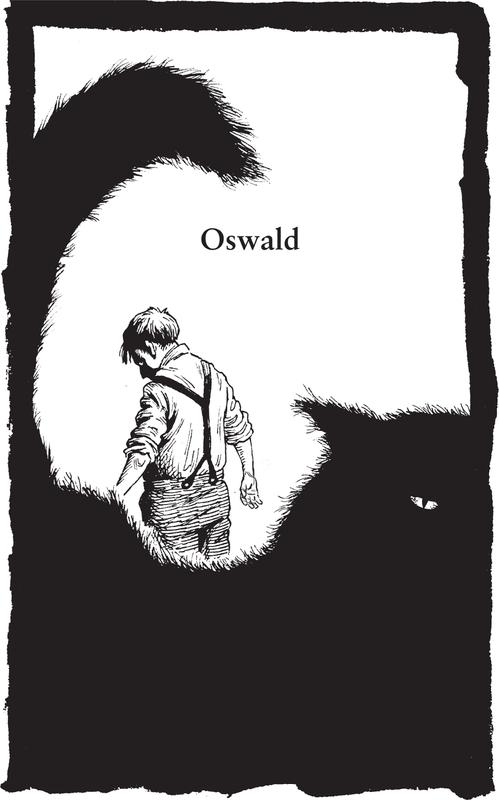

cats. She’d had a fair few of them over the years, but by the time I’m talking about, at the end, she had three: Tabitha, Tiptree and Oswald. And when she was very ill, with only months to live so the doctor told her, and she couldn’t really cope any more, her nephew came to stay to help her out. He shopped and he cooked and he cleaned and he looked after the cats.

He was a sweet boy, Roland, just lovely. And so loyal to his aunt. She treated him just as badly as she treated every other human being she ever met – shouting at him and calling him stupid and never a word of thanks for all he did – but he wouldn’t say a word against her.

He wouldn’t even speak ill of those cats, and they were right little demons, let me tell you. Tabitha and Tiptree were bad enough, but Oswald, oh dear, Oswald was an unholy

terror

. Times I saw poor Roland with scratches on his arms and face, and he’d tell me some tale about tackling the brambles in Aunt Helena’s garden, but I could see: those scratches weren’t from any brambles.

Now, like I say, old Dr Whitfield had said Helena had only a short while left to live. Two or three months, if she was lucky, he said. Well, Helena was as bloody-minded and stubborn about that as she was about everything else, and she didn’t die after three months and she didn’t die after four, or six, or even a year … In fact, Dr Whitfield himself died before Helena did. Went to bed one night telling Mrs Whitfield he had terrible

indigestion and it turned out he was having a heart attack. It might not have been fatal if Mrs W had been upstairs with him to get help, but she was downstairs in a huff because he’d blamed her dumplings. Silly man. Still, if he

had

lived, then it wouldn’t have done much for his reputation, would it? People knowing that he couldn’t even diagnose his own heart attack!

Anyway, Helena lived on for three years and a little bit more before she finally passed on, and she didn’t get any kinder in her last days. That poor boy Roland took all manner of abuse from her, and it wore him down, you could see. Oh, he’d been a lovely lad when he arrived. He was a fine boy: bright and cheerful and kind. Couldn’t do enough for you. And he was still trying his best at the end, but you could see that some of the old woman’s poison had seeped in. He’d be just a little bit short with you, and he always looked so tired, the poor boy. He looked, well … he looked broken.

But even then, when Helena did finally die, he was proper upset about it. I wouldn’t have blamed him if he’d had a party. I would have. There would have been plenty who’d’ve been happy to celebrate the occasion. But there was a decent turnout at the funeral, for all that. More for Roland’s sake than out of respect for the departed, mind, and old Mrs Collins just along for a good feed at the wake as usual. Couldn’t resist a ham roll, that one. It was a sunny day for the burial, and you couldn’t help feeling like it was a rather jolly occasion. Not really funereal at all. I swear the vicar

was absolutely

beaming

at times, you know, when he thought nobody was looking.

A few days later and they had the reading of the will. And the thing was, with no friends and no other relatives (her rich husband had died

years

before, and who could blame him), Helena had left Roland

everything

. Now, there was a

bit

of money – not a fortune, but a tidy enough amount – but the main thing was that he got the house.

Only there was a catch. There was a condition in the will that Roland couldn’t

sell

the house, or at least not yet. He had to live in it and carry on looking after the cats, and only after they’d all died could he sell it.

Well, you can imagine, he wasn’t especially keen to stay. He’d not exactly had a whale of a time in that house and he certainly wasn’t fond of those blessed animals. But the house was in a right old state from generations of cats roaming around the place scratching and chewing and doing their business wherever they pleased, so what Roland decided was that he’d stay living there while he got the place tidied up a bit, then by the time the cats had all passed on and he was able to sell it’d be looking at its best.

So now we see a bit more of Roland around the village for a while, and he seems a bit happier now, with his aunt gone, but it doesn’t last long. You see, as dreadful as Helena was to everybody, she always spoiled those cats, and Oswald in particular. But now Roland’s in charge and he isn’t treating them like

royalty, like they’re used to, so they act up proper terrible like. Roland’s trying to make repairs around the house and they’re tearing around the place, or they’re fighting amongst themselves. And they’re bringing in dead mice and whatever and getting blood and fur all over the carpets in rooms that Roland’s just got clean. So you’d forgive him – anyone would – if he was proper sick of those bloody animals (pardon my French) by now. You wouldn’t blame him a jot if he wished they all just died as soon as you like and he could have a bit of peace and quiet and sell the house and go. Off to somewhere nice with no cats. But he still doesn’t complain. Well, hardly at all. And he’s still blaming the bramble patch for all the new scratches he’s got, and not a soul believes him.

And then Tabitha dies, and despite it all you can see he’s proper upset about it. Apparently she got into a fight with Oswald who chased her out onto the driveway just as Roland was backing the car out of the garage. There’s no consoling him afterwards.

If only I’d been paying more attention, I might have seen her. Maybe I could have stopped in time.

Well, there’s no use thinking like that, is there? The cat’s no less dead for worrying about it, is she? I try to cheer him up. I say, ‘Look on the bright side, Roland: one down, two to go,’ but he takes it the wrong way.

He’s still brooding on it a week later when Tiptree dies too. Just drops down dead. Old age, most likely, and you’d think there’s no way Roland can blame

himself this time, but bless me, he finds a way. He reckons that Tiptree died from a broken heart, grieving for Tabitha. Now, as I say, I think he’s a sweet boy but, ooh, this kind of nonsense gets my goat.

So now Roland is living in that big old house with no one for company except Oswald. And Oswald is just a devil. Always has been. Nice as pie for Helena – except for that one time she tried to put a collar on him and he scratched her to blazes – but a right monster to everyone else. And he’s got worse as he’s got older, and worse again for losing Helena, and again and again for Tabitha and Tiptree dying. Roland can’t get near him now, not that he would want to if he had any sense. Which, if you’re asking me, he doesn’t.

Anyway, we don’t see much of Roland around the village for a while. He’s right busy getting on with all the work around the house and it makes him a bit of a recluse. Then Mr Cutler bumps into him at the ironmonger’s over in Freckingham one day and says afterwards that he doesn’t look so good. And Mrs Curtain spots him in his car, freshly scarred she says, over near Westerby. I wonder if he’s eating properly and drop by once in a while with soup or a stew, and he takes it from me and says thank you, but he doesn’t smile and he never once invites me in.

He’s a hard worker, though, I’ll say that for him. Works all hours on the house, he does. He does the small jobs himself and pays to get men in to do anything he can’t manage: you know, plastering and plumbing

and such. Of course Oswald hates all the disruption and kicks up a hell of a fuss (’scuse my language) and that slows things down a bit. Some small furry dead thing gets brought into the house in the night and ends up in the plasterwork. And the plumber, eating supper in The Crown one evening, shows us all a nasty gash on his leg and boasts about the bonus Roland paid him in compensation.

A couple of days later Roland gets hurt too. A bloomin’ great bookcase topples over when Oswald jumps from the top of it, and Roland’s right underneath it when it falls. Might have killed him, easy as pie. Must have been a heck of a weight. Dangerous things, books – I won’t have ’em in the house. Well, anyway, it doesn’t kill Roland, but it does put him in hospital for a few days. I think at this point that it feels pretty much like a holiday for him, lying in bed all day, everything laid on, and not a cat in sight. He’s as chirpy as I’ve seen him in a long while when I go and visit. Then, when he gets home, he finds that Oswald has finally gone to meet his maker while he was away.

It’s not been a dramatic death; it’s just that the years have finally caught up with him. It was probably only spite that was keeping him going anyway, I reckon, so with nobody else about to make suffer he probably couldn’t see the point any more. Roland finds him curled up in his favourite spot: in front of the fireplace in the sitting room. He looks so peaceful, but it’s hard for Roland to appreciate because of the stench. It turns

out that in his last moments Oswald has lost all control of his bowels. All over one of Helena’s best rugs too. Worth a fortune, it is. Well,

was

worth a fortune.

Now, at this point Roland’s meant to be taking things very easy for at least the next couple of days. But he’s not been back five minutes and he’s already out in the garden burying Oswald. It’s a big hole he digs too, because he buries him all wrapped up in the rug, which is beyond help. Mrs Curtain drops by to see him and finds Roland standing on top of the new grave, pressing down the earth, shining with sweat. And there’s no disguising his smile. He looks as if a weight has been lifted from him. He looks relieved and happy, and there’s not a person in the village who would begrudge him that.

He’s even seen in the pub later, getting tiddly on cider, and he’s quite the happy chatterbox. It really looks like he’s turned a corner.

But then a day or so later, back working on the house, there’s some kind of problem with the upstairs lights: they go off sudden-like one night. So Roland calls in an electrician the next day, and he takes a look and finds a break in one of the wires.

‘Looks like it’s been gnawed through,’ this fella says. ‘Probably mice,’ he says. ‘You should think about getting a cat, you know,’ he says.

Roland says he’ll buy a mousetrap. And he does. He nips over to Freckingham and picks one up at the village store. Lovely little shop, that. Beautiful pork

pies. Anyway, Roland goes home, sets the trap with a lump of Cheddar for bait, then goes to The Crown for his supper. Well, the cider gets the best of him again, so he’s a little bit wobbly walking back up the road afterwards, but he manages to remember to check the trap when he gets in, and the funny thing is: it’s been sprung, but there’s no mouse. And the bit of cheese is just by it, which is odd. But he thinks maybe he just didn’t set it right, so he sets it again, really carefully this time, and puts it back. Then he flops down in the good armchair and, what with the cider and the walk home and everything, he soon dozes off.

He’s there a good while, slumped over to one side and one arm hanging down, but perfectly content and sleeping like a baby, despite hanging off the chair all awkward-like.

It’s an hour or so later when he starts to wake up. His eyes are closed, and he’s still not thinking anything, but he’s just faintly aware of something touching his hand. It’s the lightest touch, a lovely feeling, brushing slowly across the back of his hand, just gently stroking him. Soft as silk it is. And his eyelids begin to creak open, and his mind starts to focus, and he thinks: not silk. No, not silk. Something else.

Fur.

Oh, he’s awake now! Wide awake all of a sudden, and he pulls his hand up ever so fast, like it’s been scalded, and he shrieks the same way, and his eyes have snapped wide open. He stares down at the floor and

there’s nothing there, of course, so he looks around the room, everywhere, all frantic-like. And, bless me, but there’s nothing there at all. So he’s sitting there, the one hand holding the other, telling himself he dreamed it, but his skin is tingling, and his heart is racing. And the mousetrap has sprung again.

He sits there trembling, staring at it for a while. Then he goes to his bed and he pulls the covers up and he leaves the lamp on. All night he doesn’t sleep for more than ten minutes at a time, and the slightest creak or squeak around the old house wakes him up and sets him trembling.

When dawn breaks, as usual there’s no bird singing to let him know. Helena used to say that Oswald had scared all the birds away years ago, but I reckon it’s just as likely they were avoiding

her

.

Roland’s been dozing, but he feels like he’s not slept for days. His head is a right old muddle, all fuzzy and jumbled. He turns off the lamp, gets up, and goes over to the window and looks out. And, oh, it’s a beautiful morning. Just lovely. The bedroom window looks out over farmland and the sunlight is lighting up the frost on the ploughed fields, and the sky is clear.

He opens the window and breathes in some of that fresh morning air, and it’s as delicious as a drink of cold water on a hot day. Just for a moment he stands there and, oh, he feels so calm. His whole world is still and silent, and he likes it that way.