Read This Book Is Not Good For You Online

Authors: Pseudonymous Bosch

This Book Is Not Good For You (12 page)

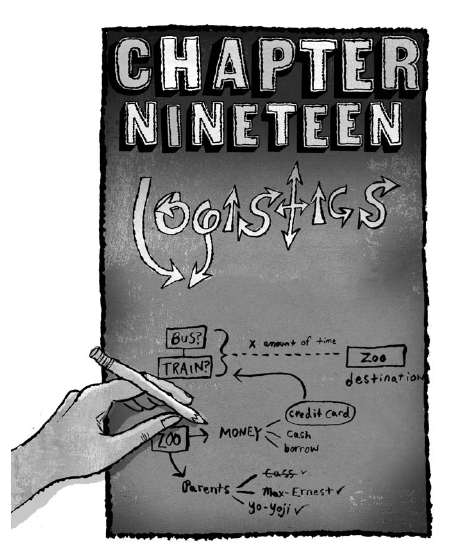

Even with the combined Internet searching talents of three exceptionally smart young investigators, it took several hours to identify every zoo in North America. But only a few zoos were so big they might conceivably hide a chocolate plantation. By the time Max-Ernest’s parents arrived to collect him and Cass, the kids had settled upon the likeliest candidate: Wild World Wild Animal Park.

Wild World was known for its “eco-hoods”: mini artificial ecosystems that recreated various climate zones and animal habitats from all over the planet. The largest eco-hood in Wild World was their rainforest (at least they called it a rainforest), and it was there our friends hoped to find the Midnight Sun—and Cass’s mother.

The question was logistical: how to get there?

THE PARENT PART

was easy.

Yo-Yoji’s parents gave him a lot of freedom—especially in summertime. The next morning, when he said he was going to the beach with his friends, his parents were just glad he was going to be outside rather than spending the day on his computer.

“I think I’m going to crash at Max-Ernest’s,” he said. “But if you want to talk to his parents, you should call on my phone. ’Cause I don’t know whether we’ll be at his mom’s or his dad’s—it’s so confusing.” (Yo-Yoji was especially pleased with this last detail—it seemed so plausible.)

The only glitch was that he had to leave wearing his bathing suit. He changed behind the trash cans in back of his house, trading board shorts and beach towel for a pair of jeans and his new favorite T-shirt. (The shirt was decorated with a Japanese character written graffiti style—the kanji, he’d been told, for samurai.)

Max-Ernest’s parents normally fought over every second of his time. But they’d become so preoccupied with each other (that morning found them having coffee at Max-Ernest’s mother’s half-house; later they’d be having an afternoon snack at his father’s) that they didn’t offer a single objection when Max-Ernest said he and Cass and Yo-Yoji were going to the movies and that he wouldn’t be home for a long, long time because they were going to a “triple feature.”

“A triple feature? That sounds triple-icious!” said his mom, smiling at his dad.

“Triple-dipple-duper!” said his dad, smiling at his mom.

Max-Ernest stared at his parents: were his eyes deceiving him or were they holding hands? Catching his glance, they quickly let go of each other.

Max-Ernest left them with an uneasy sense that his parents’ bodies had been taken over by another couple—an alien couple.

Cass’s mother: well, that was the point, wasn’t it? The upside of her having been kidnapped was that she wasn’t around to forbid Cass from running off to save her.

THE HARD PART

was money.

When they pooled their resources they had only enough for the train tickets; there was no money left over for admission to the wild animal park, not to mention the trip home.

Then Cass remembered the credit card her mother kept in the drawer in the kitchen. It was for emergencies only, her mother had told her. But if her mother’s very own personal kidnapping didn’t qualify as an emergency, what did?

Perhaps money wasn’t the hard part, after all.

THE TRAIN PART

was easy in one way, hard in another.

Destination: Xxx Xxxxx

Estimated time of arrival: X:00

Naturally, I can’t tell you where their train was going, or how long the ride was supposed to be. To be more precise, I can tell you—that is, I am able to tell you if I choose—but I won’t tell you. For reasons with which you are by now all too familiar.

However, I feel I should tell you about a minor, very minor, episode that occurred as they boarded the train. Only because it caused Cass so much consternation:

“After you,” said Yo-Yoji.

“After me what?” asked Cass, confused.

“Um, for you to get on the train first…”

“Oh, right… You mean ’cause I’m a girl or something? That’s dumb!”

“Whatever.” Yo-Yoji shrugged and stepped onto the train.

Cass let Max-Ernest board before following her friends into the train car. Yo-Yoji’s politeness was so weird and out of character that it had caught her off guard. But she shouldn’t have snapped at him like that. He probably thought she was still angry at him. Was she still angry at him? she wondered.

Automatically, Max-Ernest slid over to the window, making room for Cass—just as he did on the bus every day during the school year. Cass was about to sit down next to him—just as she did every day during the school year—when she noticed out of the corner of her eye that Yo-Yoji had also slid over for her. Or started to.

Cass’s ears tingled with panic. If she sat down with Max-Ernest, Yo-Yoji would definitely think she was still angry at him and he might even get angry at her. But if she sat down with Yo-Yoji, she would be making a big statement—after all, she sat next to Max-Ernest on the bus every day during the school year—and she knew from experience that Max-Ernest would be very hurt. She’d learned the hard way that he was more sensitive than he seemed; he might not be good at feelings, but he definitely had feelings nonetheless. Not to mention the fact that he was already sore about her lying to him about Pietro.

All things considered, she decided that sitting next to Max-Ernest was the less risky of her two options. (Of course, when I recount her thought process, it seems like she took a long time coming to this decision, but in reality it only took a second.)

If Yo-Yoji was in any way hurt or angry he didn’t show it. However, let the record show that when Yo-Yoji again had the chance to offer Cass a seat—on the tram at Wild World—he didn’t even glance her way.

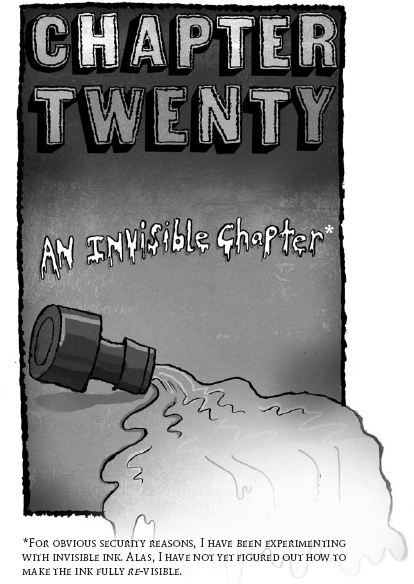

Th

not ear ove the scr ams f the onkeys

olate plantatio???????????????????????? s

?

?

?

?

st

?

?

?

?

??????????Mauv?? s in h r pers nal chambers.

??????????????V ry

?

??????un stre m d thro th curta n, uminatin er gold ??ress nd sign tur diam ds.

?

?

?????r. L peere ver r oulder. “You l k lov y, my d ling.”

?

?

C

?

?

on th desk wa????? of

?

?

?????????????ook d alarm ly lik Cas.

“Ar ou qu t cert n thos re her p ents?” he a ked.

“????????????????.”

?

?

“We’v b n so cl se in the??????! I don’

?

??????tt

?

??R

?

?

?

??????????erces soci

??n

?????????????????????????????Midn

????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????o squishy

?

?

?

?????????????????????????????99 of th m!

????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????s

?

???????????????????????By now Ms M

?

?

????r l

???????????????????????????????????????????????????????????said sternly.

?

?????q

?

?

?

?

?

????????????????????????????????????????z

?????s ch a shock!”

?

?

?

?????e

?

?

?

?

?

?????????????????????????????????nd again

…You can tell he’s an African Elephant and not an Asian Elephant by looking at his ear—see how it’s shaped just like the continent of Africa?”

The woman who said these words wore a khaki jacket and matching pith helmet. Mosquito netting hung over her face. She looked as though she were on safari.

That is, aside from the microphone in her hand. And the fact that she was standing at the front of a tram.

She gestured to the tall gray animal standing about twenty feet away. The elephant flapped its ears obligingly—then spit water out its trunk, as if disgusted with the show.

“The African Elephant is officially listed as endangered. Does anyone know the difference between a vulnerable species and an endangered species?”

The tram was silent—no one, apparently, was able to answer the tour guide’s question.

Then, in the very back, a girl with pointy ears piped up: “Vulnerable means a ten percent chance of extinction in the next hundred years. Endangered means—”

The short, spiky-haired boy sitting next to her interrupted: “Endangered means there’s a twenty percent chance of extinction in twenty years.”

Their taller, Asian friend, sitting across the aisle, shook his head. “I thought we said we weren’t going to call attention to ourselves,” he whispered. “You guys are such know-it-alls.”

“Nobody can see us,” said Cass defensively.

“Yeah, nobody can see us,” said Max-Ernest. *

The tram had two sections hooked together like train cars; and from their vantage point the three young adventurers could see not only the elephants standing on the side of the road, but also the tram riders up front, gawking at the elephants.

The tram was painted with a camouflage pattern that suggested military maneuvers and jungle adventures, and on its sides were the words:

WILD WORLD

The World’s Wildest Wild Animal Park

Go WILD! Go WILD WORLD!

But so far, the wildest part of the ride had been a too-close encounter with the tongue of an animal named, according the tour guide, “Jerry, the Very Merry Giraffe.”

In his lap, Max-Ernest held the glossy Welcome to Wild World map they’d received when they bought their tickets. It showed how the animal habitats at Wild World were divided into eco-hoods—the ecological neighborhoods the kids had read about earlier—with names like Misty Marsh, Dead Man’s Desert, and Rainbow Rainforest.

This last eco-hood, the rainforest, was by far the largest, occupying nearly half the area on the map. It was there, our heroes hoped, that they would find the hidden chocolate plantation and perhaps even the new secret headquarters of the Midnight Sun.

Currently, the tram was winding its way through the park’s version of African grassland—SERENGETI SAVANNA. The sun was just starting to go down—this was, after all, the SUNSET SAFARI tram ride—and the landscape glowed gold. In the distance, a flamboyance of flamingoes was silhouetted, gathered around a watering hole. **

“It’s kind of like we got to go to Africa, after all,” said Max-Ernest. “How ’bout that?”

“Kind of,” said Yo-Yoji, whose parents had made him look at one too many pictures of the real Africa. “And kind of not.”

Cass looked out across the rolling, grass-covered hills of the manmade savanna. Maybe it could be Africa, she thought, if you ignored all the popcorn and candy strewn along the side of the road.

As they rounded a turn, an excited murmur rippled through the tram. A large yellow sign was posted on the hillside:

ENTERING LION COUNTRY

KEEP ARMS INSIDE TRAM AT ALL TIMES!

But the only animal in sight was a zebra ambling away. If there were any lions nearby, he didn’t seem very scared of them.

“Where are the lions? I want to see a lion!” shouted a child up front.

“Sorry—looks like they’re sleeping,” explained the tour guide. “Did you know the average lion sleeps over twenty hours a day? That’s why they call them the king of beasts—because they’re so lazy!”

The crowd tittered.

“Can you hear that ringing sound? Believe it or not, those are frogs croaking. We are now approaching Rainbow Rainforest.”

This was our friends’ cue to start paying attention. Cass, Max-Ernest, and Yo-Yoji all craned their necks, straining to look ahead.

Rainbow Rainforest definitely lived up to its name—at least if you weren’t expecting a real rainbow or a real rainforest.

As soon as they crossed into the (so-called) rainforest, hidden sprinklers drenched the tram with water; it was like driving through a torrential downpour in the tropics. (Or maybe just like driving through a car wash.) Meanwhile, a strategically placed floodlight created a prism effect—a rainbow. Of sorts.

Unlike SERENGETI SAVANNA, which was wide open with views in all directions, the rainforest was dense and dark and, if you were somebody like Max-Ernest, extremely claustrophobia-inducing. The leaves were so big, and the trees so tall, that you couldn’t help feeling small—as if you were looking at the world through the eyes of an ant.

“Out in the real world, more animal species live in rainforests than in any other type of environment—and that’s true here at Wild World, too. We have over twenty species of frogs, including one species that flies. And twelve kinds of monkeys—though no flying ones. You’ll have to visit the Wicked Witch of the West to find those!”

As the tram drove deeper into the rainforest, the park visitors experienced a kind of sensory overload. While tropical birds cawed from every direction, the frog croaking grew louder and louder until it was almost deafening. The last rays of sunlight penetrated the trees from above, casting shadows in the shapes of vines and leaves, and creating dizzying patterns of light and dark, brown and green. The air was so pungent—with honey and cinnamon and vanilla, but also with musk and mold and much fouler scents—that they had to hold their noses.

All in all, the rainforest was not an easy place to look for a hidden chocolate plantation.

The kids heard no shouts between invisible plantation workers. They caught no whiffs of chocolate floating through the air. They saw no tractor tracks buried in the mud. No secret messages tied to tree trunks. No signs of illicit activity whatsoever.

Then again, all those things could have been there—and they still might not have been able to detect them.

Boldly, Cass walked up the tram’s center aisle and asked the tour guide whether there had been an old zoo where Wild World now stood. But the tour guide said that if anything like that had ever existed, she didn’t know about it. And it certainly didn’t exist now.

Cass climbed back into her seat and stared out into the shadows. It was now almost completely dark in the rainforest—the only illumination coming from the lights of the tram.

“This is crazy. How’re we supposed to see anything?”

“How’re we even supposed to think?” echoed Max-Ernest. “It’s so loud.”

“Let’s face it—there’s nothing to see, yo,” said Yo-Yoji. “We picked the wrong zoo. Or maybe it wasn’t even in a zoo in the first place.”

“Yeah, you’re probably right,” said Cass, slinking down in her seat as misery weighed down on her.

The possibility of not finding her mother was too horrible to think about; and yet she couldn’t not think about it.

By the time the tram drove out of the rainforest, all that was left of the sun was a pinkish red tip peaking over a hill.

“Hey, what’s that—?”

Max-Ernest pointed to a small gray tree—dead, by the looks of it—sticking out of the grassy hillside. A bright green bird was sitting on one of the tree’s skinny, bare branches.

As the last rays of sunshine slipped away, the bird flapped its wings and lurched into the sky.

Tense with anticipation, all three kids stuck their heads out of the tram and watched the bird pass overhead. There was just enough light left to see its red belly—and then its long tail waving in the wind.

There was no doubt: it was a quetzal.

“Hey, you three in back!—heads back in the tram, please,” came the order from up front.

As they watched, the bird flew straight toward the rainforest. Then veered left and entered the rainforest directly above the point where they’d entered some twenty minutes earlier—just past the lion warning sign.

“Did you hear me? Yes, you with the backpack—and your two boyfriends. If you don’t sit down in your seats I’m going to have to stop the tram!”

The kids yanked their heads back inside and sat down. Cass was so excited she didn’t even get angry at the tour guide for calling Yo-Yoji and Max-Ernest her boyfriends.

Max-Ernest pulled a pen out of his pocket and drew an arrow on the map where the quetzal had flown into the rainforest.

They were in the right place, after all.

Somewhere, deep inside that manmade jungle, lurked the Midnight Sun.