Thoreau's Legacy (10 page)

Authors: Richard Hayes

I Was Born on

Shaky Ground

Bronwyn Mitchell

THE LAND THAT MAKES UP MOST OF LOUISIANA, AT

least the southern part, consists of pieces of the Rocky Mountains, the Appalachians, and every place in between. Wind and water, snow and ice, work over time to break big rocks down into smaller and smaller rocks until the rock trades its former identity for that of soil. It can take five hundred years or more for an inch of topsoil to form.

Perhaps the mountain longs to see the sea, to taste salt water, to play witness to schools of fish, because as rock becomes smaller, it becomes more mobile. Driven by gravity, water falling onto the earth picks up whatever it can and moves it. In tributary after tributary, three quarters of North America drains into the Mississippi River through southern Louisiana.

When a river meets the sea, it slows down and spreads out into the traditional delta shape, which allows the sediment to fall out of suspension. In a geologic irony, the renegade sediment worn away from the mountains moves on to build up the land.

This is southern Louisiana’s unique story:

five deltas

and borrowed land.

Beginning at the continental shelf, pieces of thirty-one states unite in a series of layers. When the sediments breach the water’s surface, the coastal fringe is colonized by marsh grasses. The roots add structural stability, the live stems help capture additional sediment, and the decaying tissues continue the land-building process.

Rivers are dynamic. Always seeking the shortest route to the sea, they continually change course. People, on the other hand, like things to stay pretty much the same, so they build levees to control seasonal floods, thereby halting the periodic sustaining deposition of new sediment. When the Mississippi River tried to change course to flow west into the Atchafalaya River, the people responded by building the Old River Control Structure. This giant wall regulates water flow, sending a constant 30 percent to the Atchafalaya and 70 percent to the mouth of the Mississippi.

Louisiana is no longer growing. It is shrinking at a rate of one acre every fifteen minutes. Starved for sediment, the marsh is sinking into the sea. The rising sea level quickens the rate of sinking; even a few inches’ rise is significant for a land below sea level.

Each summer, in a ritual as sacred as fireworks on the Fourth of July, my dad, along with all the other dads in the neighborhood, would order a load of soil. A big truck would dump what to a kid in New Orleans seemed like a mountain of dirt—five feet high—onto the front lawn. Armed with a wheelbarrow and shovel, we would use that mountain to fill in the areas around the house that had sunk over the previous year.

Southern Louisiana is the nation’s canary in a coal mine. As Louisiana goes, so goes the country. Seventy-five percent of the nation’s population lives in coastal zones. The question is, do we have enough shovels?

Bronwyn Mitchell

is a New Orleans native now residing in Baltimore, Maryland. A onetime women’s professional football player, she is the executive director of the Maryland Association for Outdoor and Environmental Education.

Racetrack Playa

Mindy Kimball

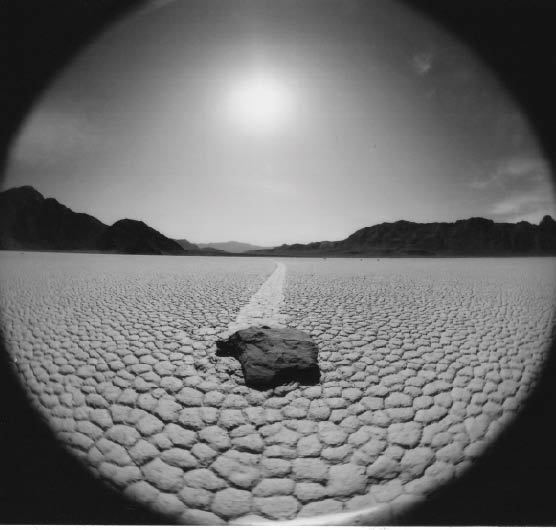

When we learned that

nobody had actually seen the rocks in motion,

I recalled a quote by Henry David Thoreau, who said, “The finest workers in stone are not copper or steel tools, but the gentle touches of air and water working at their leisure with a liberal allowance of time.” I returned to Death Valley in 2007 to present a public lecture on global climate change. I volunteer with The Climate Project, speaking to the public about the impacts of and solutions to climate change.

Mindy Kimball

is a major in the army, currently serving in Iraq as a space operations officer. A graduate of the U.S. Military Academy and California State University East Bay, she lives in Maryland with her husband and son.

The “sliding rocks” of Racetrack Playa in Death Valley, California. Photo by Mindy Kimball.

Windmills,

Talking

Jennifer Kepka

GOING BACK TO SEE MY FAMILY LAST SUMMER, WE

drove past fields of fresh-cut Kansas wheat but also past fields of towering windmills, windmills so large they felt cartoonish—science fiction come to life on the broad prairie. There are dozens of them now, and hundreds more are scheduled to join them. They cut a scattered line from the smooth concrete interstate out to the edge of Lake Wilson, waiting to turn my state’s most abundant resource—wind—into energy.

It’s strange to see windmills here, in a county where every driveway has a pickup truck, where tractors still belch diesel fumes into hazy skies all summer, where field burning isn’t up for debate, where recycling is the exception, not the rule. It’s strange, and yet it’s fitting, because it brings home the idea that global warming is really

global

, even for the places that aren’t seeing the ocean rise or the smog thicken. The windmills rise out of land that the farmers of my father’s youth didn’t worry about conserving, land that is now managed mostly by men and women with agriculture degrees, those Future Farmers of America who have studied the best ways to fight erosion, pests, diseases. Now the windmills spin on their grazing pastures, and I think the farmers must see—must begin to understand—how interconnected we all are in the world. I wonder if they see these windmills, as I sometimes do, when they flip a light switch at night. I wonder if they hear, in the steady hum and whoosh of a windmill at work, the sounds of our cities being powered, our air being relieved.

My contributions to the fight against global warming are small. I reduce, I reuse, I recycle. But I also talk. Sitting in the cooling cab of one of those guzzling pickup trucks last summer, I found myself able, for the first time in my life, to connect with my farm-raised father on issues about the environment. We stopped in the shade of a grain elevator to marvel at the massive bulk of a load of windmill stalks sitting on a still train, and we talked honestly about the ways that energy use in our country has contributed to the carbon crisis. We talked about the need for these windmills, for more of these windmills, and he expressed real dismay that he wasn’t able to put any on his farm because of recently passed state legislation.

The shadows of the

windmills loom large

in the prairie states.

They are changing minds and attitudes simply by standing up, by working slowly and gently and steadily toward a goal. They are symbols that the farmers understand, and they are machines that give me hope. To talk about them is my best contribution; to encourage their spread is my greatest goal.

Jennifer Peters Kepka

was raised in the center of Kansas but now lives in Eugene, Oregon, where she is completing a master’s degree in creative writing. Her hobbies include yelling at the TV news, forgetting to read the newspaper, and sending postcards.

At the Sign of the Heron, Turn Left

Sarah Wolpow

IF MY HUSBAND COOKED DINNER EVERY NIGHT, I

would be delighted. Should Danish house elves visit in the wee hours and run the laundry, no problem. But offer me a car instead of my bike? Forget it.

I was twenty-three years old when necessity introduced me to my bicycle. No amount of time studying Boston’s public transit maps yielded a solution that would take me between school and home and four different part-time jobs. Having access to a car wouldn’t help, because parking was either nonexistent or so costly as to make working pointless. However, for a bookworm-and-glasses type like me, becoming a Boston bike commuter was a bit of a stretch.

On that first experimental day of my new biking life, I plotted a nervous course through the muggy morning to a path along the Charles River. And there, within minutes, I received a sign that I was on the right track—in more ways than one: a black-crowned night heron sat tucked into a clump of reeds facing the river. I’d never seen one before. As Boston’s traffic sped by in its roller-coaster lanes, this exotic creature sat serenely in another world, looking for breakfast.

Later, heading home, I stopped to watch workers pulling up spent spring tulip bulbs. “Would you like a few?” they asked. A few turned out to be almost thirty, which they stuffed into every available pocket and which bloomed riotously in my garden for years. By the time I carried my bike down the basement stairs that night, I was hooked.

Tens of thousands of miles later, I’m still enchanted.

Oh, the sights you can

see from your bike

that you miss from a car!

Oh, the good food you can eat after all that exercise! Oh, the ease with which you can park! Oh, the money you can save! Oh, the flocks of turkeys you can scatter as you coast down hills in the fall!

But putting aside the boundless passion of the converted, I recall myself to the theme of this book: the climate crisis. Transportation is responsible for more than a quarter of the greenhouse gas emissions in this country. To solve global warming, we must solve transportation. A Canadian task force on sustainability summed it up like this: our transportation system must meet people’s needs, allow future generations to meet their needs, support a high quality of life, and be affordable, nonpolluting, technically possible, and powered by renewable energy.

The bicycle, the amazing bicycle, is all these things. A person on a bicycle is more efficient (in calories expended per pound and per mile) than any machine ever built and any creature that flies, walks, or swims. Can the bicycle meet people’s needs? In the United States, less than one in a hundred trips is taken by bike, even though almost half of all trips are shorter than three miles. In the Netherlands, nearly one third of all trips are taken by bike. Go figure.

Sarah Wolpow

is a writer living in Brunswick, Maine, with her husband and two children. She worked previously as an environmental researcher and a statistics teacher.