Thoreau's Legacy (14 page)

Authors: Richard Hayes

Where Are the Butterflies?

Susan J. Tweit

FOR THE PAST MONTH MY HUSBAND AND I HAVE

hosted an accidental houseguest. She (or he—we can’t tell at this stage) possesses an appetite so insatiable that we named her Gluttonous.

Her small size and single-minded quest for food allowed Gluttonous to remain unseen among the anise flowers I cut from our kitchen garden, even as she ate them. I spotted her munching on the bouquet several days later, balanced on multiple pairs of stubby legs—clearly a caterpillar, but one I didn’t recognize, dressed as she was in wrinkled black skin speckled with white and red dots.

The next morning, the empty black gauze of that now-shed skin swung from a branch. Nearby the insect herself—surely plumper already—chewed steadily in her dazzling new skin; the green and black stripes studded with orange dots identified her as an eastern black swallowtail. Watching this unexpected guest pull an anise blossom to her mouth and eat, I remembered a friend’s question: “Where are the butterflies this year?”

Our high-desert yard and kitchen garden usually attract five species of swallowtails, plus monarchs, sulfurs, painted ladies, fritillaries, western whites, and common blues. Anise swallowtails are normally so abundant that I plant extra anise in order to feed the plump caterpillars.

But not this year, when every butterfly has been cause for remark. Until this accidental houseguest, in fact, I hadn’t found a single swallowtail caterpillar in the garden. My plants had flourished unmunched.

What has changed? After a decade of increasing drought, this year’s weather patterns oscillated wildly, bearing out the predictions for global climate change in our region. First came a winter snow pack so abundant that it broke records, and then nothing: no wet spring snow, no summer rain until it was too late to do any good.

Watching our caterpillar houseguest chew another flower, I counted out the weeks and calculated that

she would

metamorphose

just in time for winter, tricked by abnormal weather.

Over the next few weeks, Gluttonous ate her way steadily through the anise bouquet, growing larger and plumper by the day as autumn flared gold outside the windows. One morning she slung herself under a branch of anise, held by her stumpy pairs of hind legs and one glistening strand of white silk. Forty-eight hours later, her striped skin had hardened into a pale green chrysalis. The miracle of metamorphosis had begun—and snow painted the peaks white.

We debated what to do with our nascent adult eastern black swallowtail. She has no future inside or out. Yet she is the only butterfly our garden produced this year.

If this heartbreaking hatch of a single caterpillar, whose maturity comes too late to seed future generations, is the gift of global climate change, I grieve for us all. Because what we are losing is not just a single species but the thread of connection with the everyday wild that secures our place in nature’s community.

Susan J. Tweit

is a plant ecologist by training and the author of twelve books, including her latest, a memoir titled Walking Nature Home: A Life’s Journey. She lives with her husband in a house heated and cooled by the sun in Salida, Colorado.

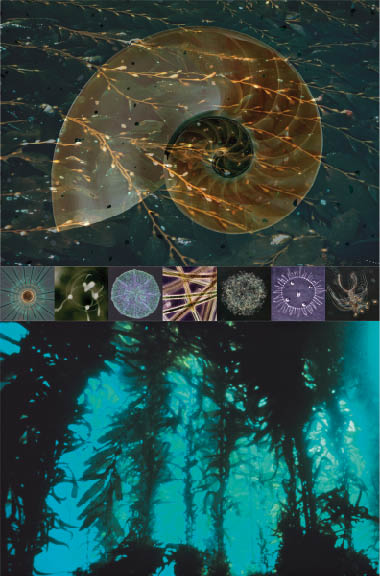

A Chambered Nautilus

Ursula Freer

Almost all mollusk shells are made of aragonite, a naturally occurring crystalline form of calcium carbonate. If we continue to follow the fossil-fuel-intensive scenario outlined by the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,

by 2060 the oceans will likely become so acidic that aragonite will start to dissolve.

Ursula Freer

is a painter and digital artist working in Sante Fe, New Mexico. Her work is primarily devoted to the beauty of the natural world.

A chambered nautilus,

Nautilus pompilius,

phylum Mollusca, class Cephalopoda. Digital collage by Ursula Freer.

Salmon in Alaska

Sue Mauger

I HAVE WATCHED KING SALMON SWIM BY ME ON

their return to the Anchor River; over Memorial Day weekend the Chinook wend their way past wader-clad fishers at the river mouth as they head upstream to spawn. They swim along a channel that continually reworks itself, shifting gravel bars, moving downed cottonwoods, searching for new angles of repose after the two hundred-year floods of 2002. The sediment-rich waters flow out of the Caribou Hills; snow is still melting from the two-hundred-square-mile watershed, which is virtually undeveloped compared to the Lower Forty-eight.

The returns of king salmon to the Anchor River have been strong, even though the forest has died. After the warm, dry summers of the 1990s, the bark beetles swarmed in dark clouds and ate their way across 1.4 million acres of the Kenai Peninsula. The dead gray trees that remain after the salvage logging and windstorms are a reminder of the forest that was.

I first stepped into the Anchor River in 2000, soon after the beetle infestation swept through. I came here in response to concerns from local citizens about the health of the watershed, to answer questions about whether the river could still support salmon after such dramatic change. I have now been studying this river for eight years, and what is most clear is that the change continues. My data tell me the river is warming.

Temperature data loggers show that water temperatures on the Anchor River, as well as on other salmon streams in south-central Alaska, are rising as air temperatures rise. Stream temperatures soared above 70 degrees F in the summers of 2004 and 2005. For families and communities that rely on salmon for commercial, sport, or subsistence fishing, this is ominous news, because high stream temperatures make fish increasingly vulnerable to pollution, predation, and disease.

The thought of warmer weather intrigues Alaskans. Who wouldn’t welcome the prospect of summer walks on the beach without a parka? But the threat of warming winters clashes with the notion of healthy salmon populations. Climate change will eventually reduce our snow pack, shortening the snow-melt period that feeds our rivers. Then, with less water in the channels, summer stream temperatures will rise even faster. Our beloved salmon runs will suffer.

I moved to Alaska from Oregon, where salmon have succumbed to a long list of harms.

Here on the Kenai Peninsula, we have

a rare and important opportunity

to make smarter decisions

about land use and greenhouse gas emissions, decisions that will have a direct impact on the long-term sustainability of Alaska salmon. My work now is focused on providing communities and policymakers with the information they need to ensure that our magnificent stream systems, like the Anchor River, retain as much ecological resilience as possible in this time of unprecedented change.

Sue Mauger

is the science director for Cook Inletkeeper, a community-based nonprofit organization focused on habitat and water-quality protection. She lives in Homer, Alaska.

Dolphins in the Water

off California

Maddalena Bearzi

Dolphins are vulnerable to global warming even if the effects on them are not immediately evident.

Changes in weather patterns

and the ocean’s increasing acidification as it absorbs more and more CO2 is likely to disrupt the habitats and distribution of the dolphins and their prey. Even increasing susceptibility to disease—as my own studies reveal—lowers reproductive success, and survival rates are linked to a warming ocean environment.

Maddalena Bearzi

is president of the Ocean Conservation Society and coauthor of

Beautiful Minds: The Parallel Lives of Great Apes

and Dolphins. She lives in Marina del Rey, California.

Dolphins in the water off California. Photo by Maddalena Bearzi.