Three Cups of Deceit: How Greg Mortenson, Humanitarian Hero, Lost His Way (6 page)

Read Three Cups of Deceit: How Greg Mortenson, Humanitarian Hero, Lost His Way Online

Authors: Jon Krakauer

The fact is, almost every person Mortenson encountered during his visit to Ladha treated him graciously. Only once was Mortenson made to feel less than completely welcome: Near the end of July, the South Waziristan Political Agent

heard

that a foreigner was vacationing in Kot Langerkhel, prompting government authorities to ask Naimat Gul Mahsud to escort Mortenson out of the banned tribal areas as soon as possible. A few days later, Naimat Gul drove Mortenson to Peshawar International Airport and put him on a plane for Islamabad.

When the residents of Ladha bid goodbye to Mortenson, they did so with affection, and they believed the feeling was mutual.

“

Years later,

”

says Naimat Gul,

“

when I scanned through the book

Three Cups of Tea

and read that Greg had been abducted and threatened with guns, I was shocked. Instead of telling the world about our frustration, deprivation, illiteracy, and

tradition of hospitality, he invented a false story about being abducted by savages. I do not understand why he did this.

”

3

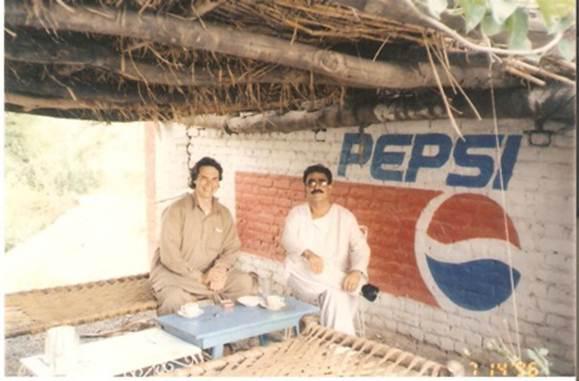

Greg Mortenson (standing, center, holding an AK-47 rifle) with some of the men he would falsely accuse of having kidnapped him for eight days in July 1996. Mansur Khan Mahsud is on the far right.

Photograph Courtesy of: Naimut Gul Mahsud

"Instead of telling the world about our frustration, deprivation, illiteracy, and tradition of hospitality," says Naimut Gul Mahsud (with Mortenson en route to the alleged kidnapping in 1996), "he invented a false story...."

Photograph Courtesy of: Naimut Gul Mahsud

Part II

ACCOUNTABLE TO NO ONE

“

[T]he duties of speaking, promoting, and fund-raising into which I have been thrust

…

have often made me feel like a man caught in the act of conducting an illicit affair with the dark side of his own personality.

”

—

Greg Mortenson,

Stones into Schools

IN THE FALL 1993, when Mortenson arrived home from K2, he immediately started soliciting donations for his

“

Khane school project.

”

A year later, he had managed to raise just $723.

“

If it hadn

’

t been for Jean,

”

muses Jennifer Wilson, referring to Jean Hoerni, her late husband,

“

Greg would still be a nurse.

”

In September 1994, Hoerni gave Mortenson the $12,000 he needed to build his first school, thereby launching his career as a humanitarian. Hoerni was a brilliant theoretical physicist who in the late 1950s played a pivotal role in the invention of the planar transistor, a new type of semiconductor that enabled the mass production of silicon chips

—

thereby transforming not only the electronics industry but also life as we know it. According to Stanford University historian Michael Riordan,

“

Hoerni

’

s elegant idea helped to establish Silicon Valley as the microelectronics epicenter of the world.

”

It also made Hoerni a wealthy man.

Hoerni had moved to California in 1952 at the age of twenty-eight, but he was born and raised in Switzerland, where he had developed a lifelong passion for mountains and mountaineering. Around 1990, Hoerni met Jennifer Wilson, their friendship gradually evolved into something more serious, and in the summer of 1993 he invited her on a twenty-eight-day, two-hundred-mile trek through the Himalaya, in the northern Indian regions

of

Zanskar and Ladakh.

“

I had never even been camping before,

”

says Wilson, a businesswoman who grew up in Iowa.

“

It was a completely new experience for me. It was amazing.

”

Four months after returning from India, Wilson and Hoerni got married. He was sixty-nine; she was forty-five.

In the fall of 1994, Hoerni happened to read Mortenson

’

s article in the American Himalayan Foundation newsletter about his quixotic scheme to build a school in Baltistan. Having trekked up the Baltoro Glacier to K2 on two occasions, Hoerni was familiar with the region, and the venture piqued his imagination.

“

I was in the kitchen,

”

Wilson remembers.

“

Jean came in and said,

‘

Look at this article about this guy who is trying to build a school. Americans don

’

t care about Muslims; they only care about Buddhist Sherpas in Nepal. No one is going to contribute to this. I

’

m going to call this guy.

’”

Hoerni, who was living in Seattle, had a brief phone conversation with Mortenson, and then wrote him a $12,000 check. After the call, Wilson recalls,

“

Jean actually said,

‘

This guy may just take off with my money. But I

’

m going to take a chance on him.

’

It was really an act of faith.

”

As soon as the check cleared the bank, Mortenson departed for Pakistan to build his first school.

In December 1996, when Mortenson reported to Hoerni that the school was finally finished, Hoerni didn

’

t care that it had been built in Korphe instead of Khane; he was simply happy that it had been completed while he was still around to hear about it. Eighteen months earlier, he and Wilson had been hiking up a mountain in the Swiss Jura, Wilson says,

“

and Jean couldn

’

t keep up with me. That was unprecedented.

”

Although Hoerni was seventy at the time, up until that moment he had been as strong as a man many years his junior; the previous summer he had trekked over an 18,400-foot Tibetan pass at a blistering pace. Concerned about his persistent, uncharacteristic fatigue, Wilson persuaded Hoerni to make an appointment to see his brother, Marc, who was a doctor in Geneva. A blood test revealed that Jean had acute leukemia. He was expected to die within a few months.

Nevertheless, for about a year after his diagnosis, Hoerni managed to remain active.

“

We weren

’

t able to hike as vigorously,

”

says Wilson,

“

but he was still able to hike. The doctors were kind of astonished.

”

In July 1996, however, while Mortenson was sojourning in South Waziristan, Hoerni underwent emergency surgery to remove his spleen. He nearly died on the operating table. Upon his release from the hospital, his skin remained ashen and he grew increasingly frail.

Back in 1995, nearly a year after Hoerni had given Mortenson the $12,000 he needed to start working in Pakistan, he paid for Mortenson to fly to Seattle so they could meet face to face.

“

They bonded immediately,

”

says Wilson. Hoerni admired Mortenson

’

s chutzpa, his willingness to think big. Both men loved the mountains. Both were visionaries, rule breakers, and risk takers

—

perennial outsiders who had scant regard for societal conventions.

Hoerni treated Mortenson like a son, and his affection was reciprocated, according to Wilson:

“

Greg told me that Jean became kind of a father figure to him, perhaps because his own father had died.

”

In the wake of their Seattle rendezvous, Hoerni was so enamored of Mortenson and his humanitarian goals that he gave him $250,000 to build five more schools in Pakistan, even though the Korphe project had barely gotten off the ground. In order to make this donation tax-deductible, Hoerni channeled it to Mortenson through a special account at the American Himalayan Foundation, designated the Hoerni/Pakistan Fund. Then, just a year later in the autumn of 1996, when it became obvious to Hoerni that his death was imminent, he established a stand-alone, tax-exempt charity for Mortenson, endowing it with an additional million dollars. Thus did the Central Asia Institute come into

existence.

As 1996 drew to a close and Hoerni

’

s decline accelerated, Mortenson flew to Seattle to spend a few days with his benefactor before the end. During this farewell visit, Mortenson made good use of his nursing skills to make Hoerni as comfortable as possible, and Hoerni seemed grateful for his presence. On January 12, 1997, not long after Mortenson returned to Montana, Jean Hoerni died, with his wife and daughters at his bedside.

*

*

*

Three Cups of Tea

(page 236), Mortenson

“

admired her determination to serve the world

’

s most neglected populations.

”

A hospice for the terminally ill that she opened in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, in 1968 captured Greg

’

s imagination as a ten-year-old growing up in the village of Moshi, 275 miles to the north, and his respect for Mother Teresa became greater still when she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979. Mortenson came to regard her as a role model, even after she faced withering criticism over the shoddy medical care her hospices provided and for lying to donors about how their contributions were used. According to

Three Cups,