Three Houses (2 page)

Authors: Angela Thirkell

But when my grandfather began to develop in a different direction from his master Gabriel he saw in his mind a type of woman who was to him the ultimate expression of beauty. Whenever he saw a

woman who approached his vision he used her, whether model or friend. Some of my grandparents’ lasting friendships were begun in chance encounters with a ‘Burne-Jones face’ which my grandfather had to find a way of knowing. As my mother grew up she was the offspring of her father’s vision and the imprint of this vision has lasted to a later generation. I do not know of another case in which the artist’s ideal has taken such visible shape as in my mother. If the inheritance were more common one would have to be far more careful in choosing one’s artist forbears. El Greco, for instance, or Rowlandson, would be responsible for such disastrous progeny from the point of view of looks.

From the Garden Studio we might have been tempted to make a forbidden excursion into the street, but the outer door was locked so back we ran into the little orchard. Small enough it was, but large enough to a child, with space to sling a hammock from pear-tree to apple-tree and a green bench for grown-ups and a bank to roll down. In those days soot had not choked the blossom and there were plenty of windfalls in autumn for us to eat when Nanny’s eye was not on us.

On the other side of the orchard was a little shrubbery where the gardener kept his tools and had a huge rubbish heap and grew a few pot-herbs. The place was memorable to me because I once in a fit of unwonted zeal weeded up a whole bed of spring onions. The gardener did not approve of our presence here, so we went round by the great flowering elder-tree and came back on to the lawn behind the house. Here, against the south wall, was an immemorial mulberry-tree, its spreading boughs supported by posts and the cracks in its ancient bark plastered with cement. After the fashion of mulberry-trees it was good to climb and good to stain one’s pinafore. Near it, also against the wall, was a little grassy mound known as Pillicock Hill. You will remember Edgar’s song in King Lear, ‘Pillicock sat on Pillicock-hill’, and there was a nursery rhyme,

Pillicock sat on Pillicock’s hill.

If he’s not gone he lives there still.

Sometimes on my brother’s birthday my grandmother had a Punch and Judy show on the lawn, as much

for our grandfather’s pleasure as for ours. He had the highest admiration for Punch and said of him: ‘I really do think Punch is the noblest play in the whole world. He’s such a fine character, so cheerful, he’s such a poet, he chirrups and sings whole operas that are not yet written down, till the world bursts in upon him in the shape of domestic life and the neighbours.’ There was also a legend that my grandmother had once given a garden party with the Blue Hungarian band, but that was so unlike all we knew of our grandparents that we accepted the tale with utmost caution. The only circumstance that we knew in any way paralleling it was when some ladies and gentlemen came on a winter afternoon to see pictures and we were sent for to the drawing-room after tea. The big room was dimly lit, its Dürers and Mantegnas barely visible, and seeing strangers I felt it incumbent on me as hostess to welcome them by flinging my arms round their necks. One of the ladies knelt down and let me hug her properly, but the tall gentleman was very stiff and though I tugged at his hand he wouldn’t bend. It wasn’t till much later that our scandalised Nanny informed us that the kneeling

lady was called Alexandra and was a princess. The tall stiff gentleman was Prince Charles of Denmark then, the King of Norway now.

On the grass, among the pear-trees and apple-trees, we played for endless hours while people came and went with jingling and clip-clopping of hansoms between The Grange and other hospitable houses. The men played bowls on the lawn and smoked and talked and the women paced the gravel walk by the long flower-bed or joined them under the trees. Though we had been at The Grange for immemorial space, there was always time for further pleasures in those days when it was always afternoon. We might be put into a hansom and taken to other gardens with studios in them where our parents would talk and pace the paths and we would play among rose-trees and apple-trees and the very sooty creeping ivy peculiar to London gardens. All through the long afternoons the gardens waited for us. Draycott Lodge, where the Holman Hunts lived, Beavor Lodge and the Richmonds, The Vale, home of the De Morgans – all bricks and mortar now. Melbury Road, even then only a ghost of its old self where the Prinseps used to have their friends in a yet more golden

age and where Watts still lived. Grove End Road, with Tadema’s stories which were so difficult to understand until his own infectious laugh warned you that he had reached the point, the agate window and the brazen stairs. Hampstead, Chelsea, Hammersmith, gardens were waiting for us everywhere and people who made noble pictures and were constant friends.

At last the long afternoon came to an end. A final visit to the kitchen regions to talk to Robert the parrot and examine the hatch for the hundredth time and the hansom was at the door. Then a drive home in the cool of the day and the little girl was allowed to sit up to supper in her dressing-gown and have baked potato with a great deal of butter till she was half asleep and was carried upstairs in her father’s arms while he sang – very slowly, so that the nursery should not be reached before the song was ended:

My grandfather died, I cannot tell you how,

He left me six horses to gang with the plough…

One more long happy Sunday had joined the pale golden Sundays that are gone. Better – to us at any

rate – than Sundays now. Though these latter-day Sundays may be real enough, to us they are but the illusion and the bygone days the reality. There is always in our minds the hope that we may find again those golden unhastening days and wake up and dream.

27

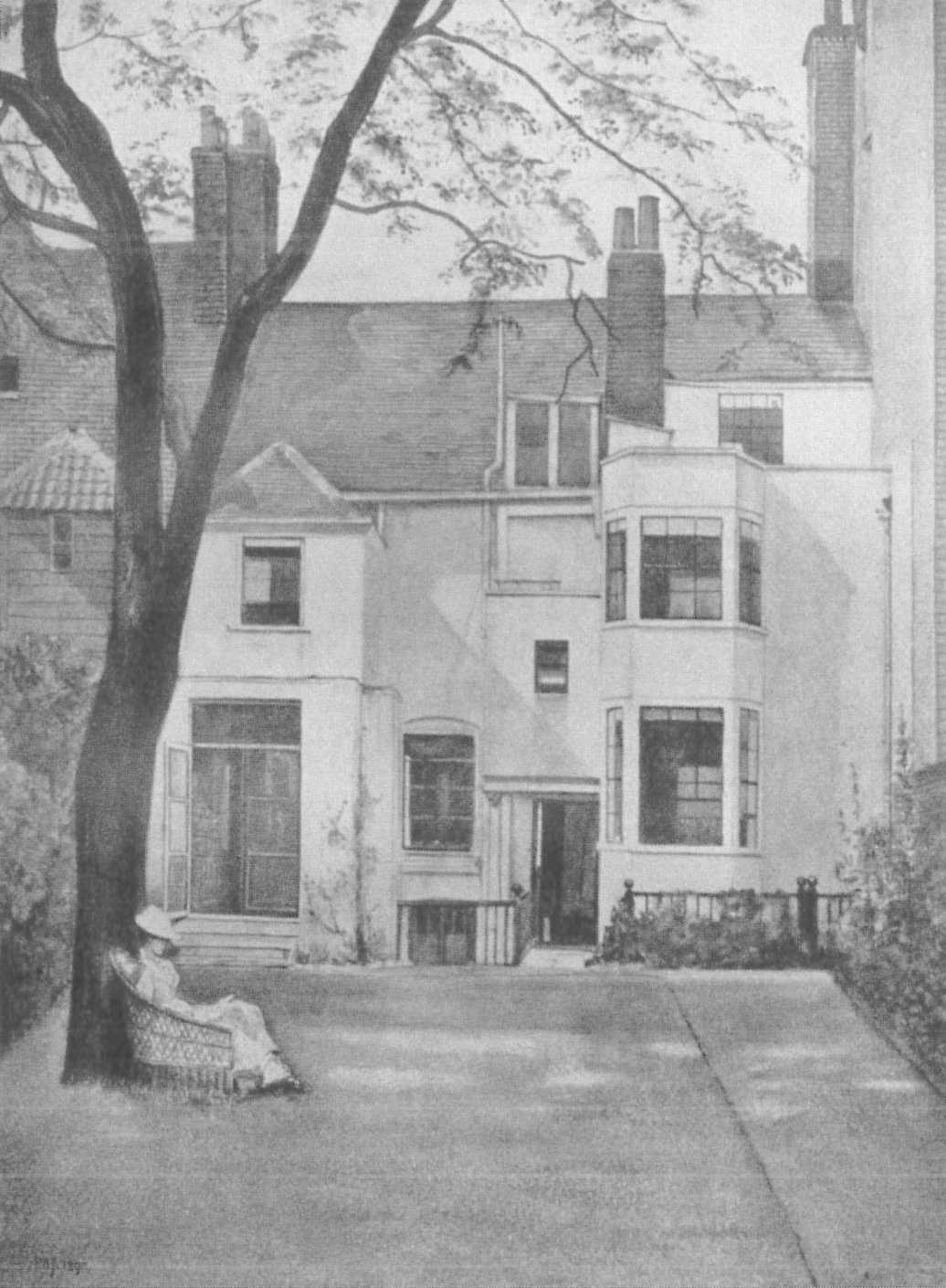

YOUNG STREET

from a watercolour drawing by the late

SIR PHILIP BURNE-JONES, BT.

It is not every one who has the luck to be brought up next door to a public house. When my parents were first married they went to live at 27 Young Street, Kensington Square, beside the Greyhound. The little house is still there and so is the public house; but it is not the Greyhound of my very young days. Then it was almost a country inn, a James II house like ours, two stories high with dormer windows in the high tiled roof, a front door in the middle and a window on each side. A small porch was built out over the front door and on its roof were two stone greyhounds couchant. It was at the ‘Greyhound Tavern over against my Lady Castlewood’s house in Kensington

Square’ that Esmond spent a wakeful night before the meeting at the King’s Arms. Thackeray’s own old house was opposite us and our landlady was Lady Ritchie who had been Miss Thackeray. Her son had been called Denis after his grandfather’s Denis Duval and my parents called their son Denis for the same reason.

Old Kensington when I knew it was a vanishing dream, but how pleasant, how romantic it was. In an old inhabitant of the Royal Borough there is a secret nostalgia for its red-brick houses, its lanes that are now streets, its hawthorn flowering gardens that are flats and garages, its little friendly shops that were long ago swallowed up by great department stores. There is hardly a street in Kensington that has not been changed even in my lifetime. Part of Kensington Square remains untouched, but the hideous tide of commerce is sweeping down upon it. On Campden Hill the great houses and gardens are falling one by one. Kensington Terrace, with its long gardens went many years ago. Scarsdale House was gone before I can remember. When first my parents went to Young Street they could look across gardens at the back of

the house to the elms of Kensington Gardens. Flats cover those open spaces now and number 27 with its neighbour Felday House is left, a little island of green among high walls and overlooking windows.

When I came back to London this winter after many years’ absence I found Lord Holland’s statue gone from the green enclosure at the bottom of Holland Park, the old brick wall and railings pulled down, a great block of shops and flats in their place. Farther up the High Street, Phillimore Terrace was being carted away – the ‘Dishclout Terrace’ of George III – and the row of houses next to it where we used to run up and down the steps was gone. Even in Kensington Gardens I found the destroyer at work, asphalting tracks that were once like country footpaths, piling up bricks and mortar at the end of Broad Walk and near the Round Pond, daring to alter the railings and borders of the Flower Walk, making germ-nests of sand in organised playgrounds where no self-respecting Nanny will let her children play. Farther afield they are setting up unnecessary monuments, some ugly, some merely common, or giving the green grass to be trodden into mud by football players so that twenty-two boys may

enjoy themselves where hundreds could stroll or sit. I cannot see that any of these changes are for the better, but the great aim of democracy is to make everything as uncomfortable as possible for the greatest number, so the minority may hold its tongue.

I have only to turn my eyes into my mind and there I find the Old Kensington of my youth. It is a bright summer morning with the sun pouring into the panelled night nursery where I and my brother sleep in our iron cribs with Nanny between us. One can put one’s head between the black enamelled bars, but it is not always easy to withdraw it. On the mantelpiece is one of those enchanting glass bottles containing a view of the Needles in coloured sand. Between the night and day nurseries is the interesting place where the water always came through in the winter. A regular accompaniment of wet weather in those days was the drip, drip of rain through the roof into a tin bath placed below it, for the house was a sad example of jerry-building, not unknown even in the days of James II. The walls were loosely filled in with rubble which had sunk lower and lower, leaving hollow passages for the rats and mice, while the lead

on the flat roof of the night nursery was always in need of repairs. As for the bursting of water-pipes that was inevitable. Winters must be much milder now, or water-pipes of stronger constitution. Then it was accepted as a law of destiny that a pipe should freeze and burst at least once in every winter and there was the excitement of streams of water pouring down inside or outside the house and the nursery bath had to be supplemented with jugs and basins. It was at crises like these that the public-house next door could be so kind and helpful in bearing a hand till the workmen came. Or there was the fatal day when my father squashed a finger in the window and my mother being young and inexperienced fled shrieking to the Greyhound, who rallied at once and sent round to lift the window sash, rescue my father, and give first aid.

Our day nursery looked out on to the street. In winter the window was kept tightly shut and sausages of red baize filled with sand were laid along the openings to exclude the death-dealing fresh air. If it was freezing and the panes were covered with fronds and leaves and stars, Nanny would put a saucer of milk out for us overnight on the window sill. Next morning we would

be allowed to eat the smutty congealed mixture. Our nursery ailments seemed to last for weeks then. Even a cold in the head was treated with infinite precaution and had its unchanging ritual. After several days in bed with a fire by day and an oil-lamp by night, we were allowed one afternoon to sit up to tea in a dressing-gown, near the nursery fire. Next day we were dressed, but confined to the nursery. On the following day we had our heads thickly muffled in shawls and were carried down to the drawing-room for a change of air. Next day, if it were fine, we were taken for a short walk between twelve and one, a scarf wound round our mouths and noses and such an outfit of woollen spencers, thick coats, woollen gloves, fur caps, gaiters, and boots, that we could hardly move. After this our convalescence proceeded on the usual lines.

Just opposite us lived a family of about our ages, and when we were all shut up in our respective nurseries with colds, we used to communicate across the street by breathing on the pane and writing a message backwards. A lengthy business – but time had no value then. Both nurseries liked to watch the lamplighter. When the early darkness had fallen we

would lift a corner of the window curtain to watch for his coming and an answering gleam of light would come from the other side of the road, till the Nannies called us away from the draught and both curtains fell again.

There were times when winter fogs descended on London and the nursery was imprisoned for days together. Sometimes the fog was thick and yellow and choking, so that we could not see the messages on the pane. On more than one occasion there was the excitement of improvising beds for guests who had come to dinner and were fogbound. Traffic was entirely held up where the fog was thick. A few brave four-wheelers went crawling along by the curb. Little boys – descendants of those link-boys that used to thrust their torches into the iron extinguishers of the Kensington Square houses – sprang out of nothing and went about with lights, offering to see people home.

The streets were curiously quiet except for distant cries from the High Street where a few carts and buses were trying to get to their homes.

At other times there was a terrifying black fog which lay like a thick cloud in the upper air, turning noon

to midnight, while the air below was comparatively clear. Then the street rang with shouts and yells and the slipping of hoofs on stones and the grinding of brakes as the traffic, caught unawares without lights, crashed into narrow Young Street from both ends, John Barker’s stables just beyond the Greyhound adding to the confusion, till the lamplighter, hastily summoned, brought his glowing pole and order was restored.

At such times my brother and I believed that great power was given to a mythical being called Mr Ponting (no connexion of the draper of that name), who lived in the coal-cellar. Clasped in each other’s arms we used to repeat his name, like an invocation of an evil spirit, till we had hypnotised ourselves into a state as near hysteria as one might wish. Mr Ponting specially favoured fogs and never manifested himself at any other time.

In spring our nursery window was as good as a dress circle seat for seeing what went on in the square. On the first of May Jack-in-the-Green still came in his bower, accompanied by chimney sweeps dressed in gay colours who danced in the street for the pennies

we threw down. On the same day all John Barker’s horse-vans were drawn up in the Square before starting on their rounds, each horse with its tail and mane intricately plaited and bound up in ribbons and bright rosettes. Wherever we were on May Day we met charming horses all bedizened and gay, up and down the streets of Kensington. Then there were a number of itinerant musicians whom we knew by sight. The Highlander, with his Highland lass in tartans, playing the bagpipes, the girl frightening my brother dreadfully by picking him up and kissing him. The weekly German band, very clean and respectable, in uniform and peaked caps, each man with his little piece of music in a clip at the end of his instrument. The Italian organ-grinder with a monkey, in a red jacket and a little cap with a feather, who would take your penny and put it in his pouch. The man who was a walking orchestra; he had a hat covered with bells, a drum behind him which he beat with his elbows, strings attached to his feet with which he twitched cymbals, pan pipes strapped under his chin, and his hands free for five or six other instruments. The Frenchman who brought a mild bear called Josephine walking on her

hind legs, ready for buns or fruit which she managed to eat through her muzzle. These and many more were our spring entertainers.

In summer the striped sun awning was pulled down and the green window-box filled with pink geraniums and musk. Nursery tea was delicious on these hot afternoons. We would come in hot and dirty from the Square and stump upstairs. The nursery window was wide open, the afternoon sun was tempered by the blue and white awning, the scent of the newly watered flowers in the window-box came in on the light summer breeze. Outside, a watering cart was being filled from a tall red pipe which curved over a hole in the top of the tank. When the water had slopped over the top the driver would turn the red pipe round so that it did not project over the road and mounting his seat, press the pedal which released the water through the holes at the back and go off leaving little blobs of water running about, dust-coated, on the dusty road. The nursery table was ready laid, only waiting for Nanny to boil the kettle in the dressing-room next door. We were not promoted to drinking tea yet. For us there were

long refreshing draughts of milk from enormous flowered cups. I once bit a large piece out of one of them in my haste and the subsequent rivers were held up as an everlasting reproach to me. The butter was usually beginning to melt. It must have been at a cooler season of the year that I ate a half-pound pat whole while Nanny’s back was turned. There were sometimes shrimps or potted meat or water-cress. Mustard and cress we grew ourselves in the garden, or on damp flannel, so that it tasted like sucking the bath sponge.

In those halcyon days of the Civil Service my father, who was in the Education Department, as it was then called, used to get back in time for tea. When he left the house in the morning he used to tell us that he was going to earn the bread and ask us what kind of bread we would like, white or brown. According to our answer he would bring us back a white roll or a Hovis loaf at tea-time. If things had gone very well he earned enough to afford to buy shortbread, but this was not so often. His bedroom was at the top of the house, an attic room that ran from back to front. It was a treat for

me to climb the steep stairs that twisted round the great newel post which stood the whole height of the house from the basement to the top landing and visit him while he shaved. In this attic he wrote his life of William Morris, in the morning before going to work, or in the evening when we were asleep. As soon as we were tucked up in bed he used to come to the night-nursery and tell us the story of the Wooden Horse of Troy and the Wanderings of Ulysses. These story-tellings went on until, as we got older, our bedtime was too near the grown-ups’ dinner for them to be squeezed in.

Sometimes I slept in my mother’s room, where there were doves who were allowed to fly about the room. A couple of asses if ever I saw any! The gentleman dove spent all his time bowing and cooing to himself in the looking-glass on the dressing table, while the lady dove, neglecting the nest we had so neatly stuffed with artificial moss and hay, laid all her eggs from the perch on to the floor where such as did not smash at once were trodden underfoot by Mr Dove when he came home in his hobnailed boots. Their passion for hairpins and bits of string may have been a primeval

stirring towards making a nest, but it never got any farther.

One occupation I can thoroughly recommend if your heartless parents send you to bed while it is still light. You lick your finger and rub it up and down on the Morris wallpaper. Presently the paper begins to come off in rolls and you can do this till you have removed so much of the pattern that your mother notices it. Then you have to stop. Another excellent way of diversifying the monotony is to cry till your mother comes. I became an adept at working up a wholly fictitious grief till I was really sobbing. If Nanny was upstairs she came banging across the landing and told me to be quiet, but I was able to judge when she had gone down to the kitchen for her supper and then my wails increased in volume till my mother came tearing up from the drawing-room below to see what the matter was. By this means I had a quarter of an hour of her agreeable company and then, much refreshed, went to sleep. Her bedroom was only divided from the Greyhound by a party wall. On Saturday nights I could hear the singing next door quite clearly. The only song I remember was of a moral nature: