Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (34 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

The year continued in much better vein that it had begun. In September Alfred Bergmann arrived to start work at long last on cataloguing the manuscript collection. It soon became obvious that the original estimate of three to four weeks for the job was nowhere near enough, given that the existing descriptions of the pieces in the collection were woefully inadequate for a serious scholarly catalogue. But at least he was able to draw on the

resources of Zweig’s well-organised library and his collection of manuscript catalogues. Despite the long delay Zweig himself was very pleased and excited at the prospect of finally seeing, in black and white, how all the separate sheets he had added to the collection over the years fitted together to form a coherent whole. On the day of Bergmann’s arrival in Salzburg Zweig had waited impatiently for him outside the Hotel Stein, and escorted him straight to his new workplace up on the Kapuzinerberg. Here Bergmann was fully occupied over the coming weeks with sorting and organising the manuscripts, and in the process was able to observe the everyday life of best-selling author Stefan Zweig at first hand. He seldom got to see him before lunchtime, since Zweig, true to his old habit, spent the morning in bed working on new texts. Bergmann recalls: “If he had finished his work he liked to put in an appearance at the table where I was compiling the catalogue. He would pick up the manuscript I was working on, and more often than not tell me the story behind its acquisition, then he would scan through what I had written about it, and if he was not satisfied he would say to me in a silky tone of voice: ‘I think you could talk this one up a bit more.’” While Bergmann is at pains, here and elsewhere, to note Zweig’s warmth and amiability, the latter’s less than rigorous approach to the history of the manuscripts’ acquisition and their historical classification did strike him as somewhat suspect. The notes on the pieces in his collection that Zweig had written on index cards and file folders, and which Bergmann now used for his own work, do suggest that Zweig may sometimes have been guided by his fondness for a good story when penning descriptions of interesting manuscripts—much to the dismay of the Germanist Bergmann, who for all his liking for Zweig made a note that he had observed in him a certain “tendency to pull the wool over people’s eyes”.

22

When Bergmann left to resume work on his main project, the cataloguing of Anton Kippenberg’s Goethe collection, it seemed as if the foundation stone had at least been laid for a splendid catalogue of Zweig’s collection, which could then be completed in the years to come. Following the acclaimed premiere of his

Volpone

on 6th November 1926 at the Burgtheater in Vienna, Zweig celebrated a further triumph before the year was out—when the world-renowned music collection of Wilhelm Heyer came up for auction, he was able to acquire a spectacular piece for his manuscript collection, namely Joseph Haydn’s Variations on the theme

Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser.

It was—is—a familiar melody: the tune to the Austrian national anthem up until 1918—and the German national anthem since 1922.

NOTES

1

Stefan Zweig to Insel Verlag, 6th November 1922, GSA Weimar, 50/3886, 3.

2

Blei 1924, p 73 f.

3

Katia Mann 2002, p 49.

4

Stefan Zweig to Insel Verlag, undated [March 1925], GSA Weimar, 50/3886, 4.

5

Friderike to Stefan Zweig, 5th December 1926. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 188 ff.

6

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 29th January 1924, SUNY, Fredonia/NY.

7

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 26th January 1924. In: Briefe III, p 110.

8

Friderike to Stefan Zweig, 1st March 1924, SUNY, Fredonia/NY.

9

Stefan Zweig to Ernst Lissauer, 21st April 1924. In: Briefe III, p 115.

10

Stefan Zweig to Otto Heuschele, 27th October 1924. In: Briefe III, p 126.

11

Die Monotonisierung der Welt. In: Zweig GW Zeiten und Schicksale, p 30 ff.

12

Friderike to Stefan Zweig, 21st October 1920, SUNY, Fredonia/NY.

13

Stefan Zweig to Victor Fleischer, undated, probably 2nd February 1925. In: Briefe III, p 133.

14

Prater questionnaire, SLA Salzburg.

15

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, undated, probably 5th September 1924. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 163.

16

Stefan Zweig to Insel Verlag, 21st March 1923, GSA Weimar, 50/3886, 3.

17

Stefan Zweig to Hermann Hesse, 4th May 1935. In: Briefe IV, p 121.

18

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 12th August 1925. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 174 f.

19

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 18th July 1925, SUNY, Fredonia/NY.

20

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 10th November 1925. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 177 f.

21

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 2nd March 1926, SUNY, Fredonia/NY.

22

Notes made by Alfred Bergmann for lecture presentations on Stefan Zweig, LLB Detmold, Slg 12 No 645.

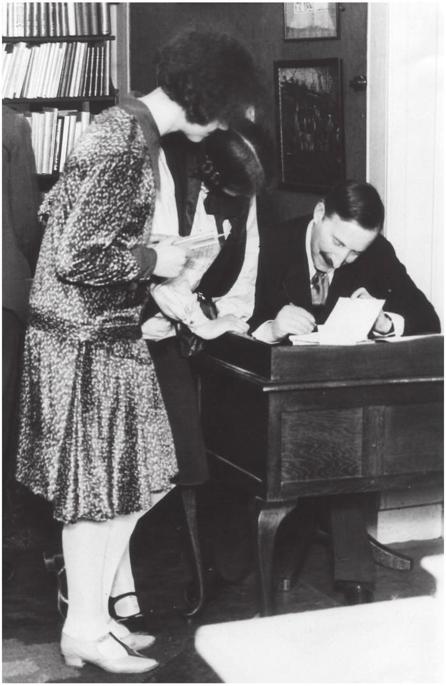

Stefan Zweig signing copies of his books in the Dijkhoffz bookshop in The Hague on the 19th of March 1929

I feel as if the screws are coming loose in the machine: the best thing would be to switch it off completely in its fiftieth year and make another attempt to experience the world, instead of describing it. Unrelenting literature fills me with mistrust, it is an unnatural condition, unless one is particularly ambitious. The less I hear about that doppelgänger St Z, the more I am my true self. And one day that’s what I’d like to be again, wholly and completely.

1

To Friderike Zweig 22nd September 1927

T

HE SUCCESS PRESAGED BY

the premiere of his new play continued unabated, and Zweig was more than satisfied: “

Volpone

is still the top money-spinner for the Viennese Burgtheater and the Dresden Staatstheater, ten days ago it triumphed in Berlin [ … ] and now it will probably canter slowly across most of the German stages”,

2

he noted with satisfaction in January 1927. His financial situation in that year seemed to prosper, so that his substantial earnings from the theatre performances could be set aside for the major auctions. In December Zweig reported to Rolland:

I have to confess that everything that good old

Volpone

brought in this year has been spent on manuscripts. But what wonders have augmented and refined my collection! Johann Sebastian Bach, the cantata

Wo soll ich fliehen hin

, complete, 16 pages; Chopin; Cimarosa; Brahms (the

Zigeunerlieder

, twenty-two pages); Mozart,

Una Marcia,

eight minuets and two unpublished minuets; Schubert; Scarlatti (large manuscript), etc etc. In the literature department, thirty-two pages of the first draft of Montesquieu’s

Esprit des Lois

, a major speech by Robespierre, [ … ] two poems from

Les Fleurs du mal

[ … ], a wonderful drawing by Goethe—you’ll find the Kapuzinerberg transformed into a museum.

At the beginning of the letter Zweig had congratulated Rolland on the purchase of a Beethoven manuscript, which his friend had been able to acquire for his own much smaller collection. A remarkable stroke of luck, as Zweig knew, since “they are getting devilishly rare, because some moneybags in Zurich is buying them up at any price (he paid 23,000 marks for eleven pages of

Fidelio

).”

3

At the time he did not know the identity of the

“moneybags” in question, since he either sent agents to bid at auctions on his behalf or else submitted written bids. Through his close contacts with dealers Zweig subsequently learnt that it was the collector Hans Conrad Bodmer, who had specialised in Beethoven manuscripts and snapped up virtually every item that came up for sale. On a few more occasions he pipped Zweig to the post, but that only made him more determined to add to his collection.

His first triumph over Bodmer was the purchase of the Beethoven song

Der Kuss

(“Ich war bei Chloen ganz allein”), which he was able to acquire in 1928. In recent years Zweig had set about systematically expanding the music manuscript section of his collection, which he had initially neglected. Nor was he content to begin in a modest way by buying minor pieces. Instead he concentrated immediately on the big names and their most important works, as can be seen from the items listed in the letter to Rolland. In 1929 he pulled off a major coup by once again getting in ahead of Hans Conrad Bodmer, assisted in this instance by the Austrian legal system. The new acquisition was not a manuscript this time, but it was a magnificent addition to his collection. Zweig passed on the news at once to his fellow collector of many years, Karl Geigy-Hagenbach in Basle:

In Vienna I’ve just bought something unique for my house direct from the heirs (albeit with a dealer acting as intermediary): Beethoven’s famous writing desk (in which the letter to his Immortal Beloved was also found), auctioned with the whole of his estate in 1827, and owned by the same family ever since. It is often—well, always—portrayed as his only good piece of furniture. One would have thought that such a priceless relic—and I would be hard pressed to think of anything of comparable value—would cost a fortune.

But this is the not the case, because here our harsh legislation came to my aid: the piece is not allowed to be sold for export, it has to stay in Austria. Furthermore the owner wanted as quiet a sale as possible, for the sake of the family name. And so the unbelievable happened: nobody else was there apart from representatives of the Vienna city council—which is hopelessly slow when it comes to purchases of this kind—and me! You’d be amazed how cheap this piece was, relatively speaking. And I may get something else from the same vendor to go with it. Anyway, I am overjoyed at the prospect of having it here, and it will be ceremoniously installed in our saloon like the jealously guarded prize exhibit in a museum.

4

As he predicted, Zweig also acquired some other items from the same owner, the von Breuning family, including a violin, a travel desk with hinged lid, a cash box and a compass owned by Beethoven, which were kept on top of the precious piece of furniture (the very one he bought instead of a motor car, according to Friderike) in the saloon of the house.

Zweig revelled in the aura surrounding objects of this kind, with their special historical significance. Similarly he felt very much at home in the ambience of his library, which was now filled with thousands of precious volumes, and he knew how to present the house and the treasures it contained to full advantage whenever he had guests. If Zweig had reason to think that his guest was receptive in some degree at least to the charms of rare antiquarian finds, he would produce manuscripts from his collection with mounting excitement. Few will have failed to notice the elation with which he spoke about the pieces in his collection, their provenance, content and history; but the number of those who really shared his passion was undoubtedly much smaller. For most people the manuscripts were what Zweig liked to refer to as a “heap of dusty, discoloured, mouldering and stained sheets of paper, a rustling jumble of letters, files and documents, the detritus of dead things already finished with, seemingly good for nothing except to be torn up and burned”.

5

As mentioned earlier, Rolland was one of the few who could really identify with the spirit of his commentaries. In his preface to the French edition of Zweig’s

Amok

, he notes the author’s passion for collecting in these terms: “He gathers up manuscripts in the feverish desire to discover in the secret of great men, great passions and great creations all the things that they keep from the public, that they have not disclosed. He is the impudent yet pious lover of genius, whose mystery he ravishes, but only in order to love it more deeply, the poet who has taken up Freud’s dangerous key, the hunter of souls.”

6

And it was true—Zweig really knew how to strike sparks from these old sheets of paper, sufficient to ignite a whole fireworks display of narrative ideas. If his imagination and delight in storytelling sometimes got the better of him, what he gained in terms of the dramatic effect of his texts made it a price worth paying. But he understood very well that interpretation could only take one so far. As he quite rightly observed: “just as the score of a song is not the song, so a love letter is not the love, nor a death sentence the death—every written record is only the cipher and sign of something unseen, that exists within its own element.”

7

In his biographical and historical studies he wisely chose almost never to discuss in detail any individual manuscripts written by the

characters he was portraying, but he drew much inspiration and material from manuscripts in his own collection and from others in libraries and archives. Whenever he was acquainting himself with a new historical or literary figure, it was generally not long before an autograph manuscript by the person in question was added to his collection.